How Charles Portis Kept Me Sane

Ray Midge didn’t lie down and give up when his wife ran off with her ex-husband, and there’s a lesson in his perseverance

My insanity began on a Friday and lasted about three weeks. What kicked it off was a nineteenth-century monument to the 17th Indiana Regiment installed on the courthouse square in Vincennes to commemorate the national unpleasantness of the 1860s. Happy to be on the winning side of the conflict, the builders had spared no expense in honoring their gallant heroes. At ground level there were, to my fated sorrow, several piles of cannon balls welded into pyramids doing their part to indicate the sky above the victors.

That was what got me: a stack of nineteenth-century cannon balls. I had my head thrown back to admire the metal soldier above, and as I moved forward to get a better glimpse of Billy Yank, my right foot came into contact with the cannon balls. The foot did not move, but my body did, and I hit the pavement like a soldier diving for cover from grape shot.

That was what got me: a stack of nineteenth-century cannon balls. I had my head thrown back to admire the metal soldier above, and as I moved forward to get a better glimpse of Billy Yank, my right foot came into contact with the cannon balls. The foot did not move, but my body did, and I hit the pavement like a soldier diving for cover from grape shot.

All seemed in place, though my wrist hurt a bit—endurable, certainly—but when we got home, my wife convinced me to go to a clinic. After taking x-rays, a young technician proclaimed triumphantly, “Hey, fellow, you broke it.” After another day of visits to doctors peculiarly interested in bones, I found myself in a cast on my left forearm, and I prepared to wait for the next four weeks to pass. I could still use my fingers, and I had an attraction now that caused perfect strangers to make jokes.

“Nothing to it,” said the woman who applied the rocklike cast. “We’ll give you some mild medication. Take it as you need it.”

“But it’s not going to hurt, is it?” I said. “It hasn’t hurt yet. Why should it now?”

“Some people suffer; some don’t. You’ll see what happens or not,” she said, and hurried off to wrap some other limb in a warm wet cloth which would become as hard as the Indiana soldier fixed on his monument.

My cast was white—the most conservative color, they informed me—and the cracked bone was held inside like the yolk of an egg laid by a granite chicken. The first night I spent with it was a restless one, but that was to be expected, I told myself. The next day and night added new discomforts, not only in the forearm but, increasingly, all over my body. Most ominously in my head.

“Ice it down,” Juanita, the physician’s assistant, told me by phone. “Take your medicine. Don’t think about it so much. Get on with things.”

“Ice it down,” Juanita, the physician’s assistant, told me by phone. “Take your medicine. Don’t think about it so much. Get on with things.”

I could take the first two steps Juanita suggested, but the third one proved impossible. In less than twenty-four hours I was doing more than slipping into darkness; I was sliding down the slope at warp speed. I began to fantasize ways to rip the cast off my broken wrist, including visions of sledge hammers, huge tin snips, pints of solvent or grease—any instrument which would allow me freedom now, and not four weeks off.

I called Juanita again, and she told me to come in the next morning. I would, I assured her, but first there loomed the prospect of another night, another disappearance of the sun over the cornfields of Illinois: a horizon where no variety of view offers relief to the hungry eye of a captive.

I crammed down all the medication allowed me, wrapped a bag of ice around the cast and what showed of my forearm, and lowered myself onto the bed beside my wife. She did her best to talk me down, to remind me that the morning would come and the cast problem would be solved. I gazed at her in sorrow. She meant well, but how could she know my agony?

“Don’t think so much,” she said. “Try to read something.” To humor her, I reached with my good hand and picked up the first book I touched on the bedside table.

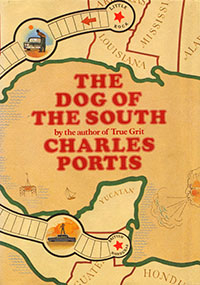

It was Charles Portis’s The Dog of the South, a novel I’d read many times, and I almost let it drop so I could try something new. But I figured I’d allow myself a quick reading of the epigraph from Sir Thomas Browne, who observed that all living creatures, from the largest mammal to the smallest mite, feel an irresistible need to move, caught up in a restless motion.

So I began working my way through Ray Midge’s narrative of what he did when his wife Norma ran off with her ex-husband. As in my own case, calamity had taken Ray by surprise, seizing him among his sixty lineal feet of books and upsetting his plans to re-enter college at the age of twenty-six, to take up teaching, to forget about his courses in Civil War history, to continue using Norma as a practice student of math, and to stay as close to home as possible.

Ray Midge was suffering. He was encased in a catastrophe akin to any number of literal casts enclosing any number of living limbs, but he was not sitting still.

Now Norma, she of the downy arm hair and the pulsating forehead vein, had fled in Ray’s own exquisitely maintained Ford Torino with Guy Dupree, an ill-tempered former journalist who had been KO’ed in every bar in Little Rock. Ray found himself lost, abandoned, encased in private misery, and the possessor of Dupree’s six-cylinder Buick sedan, holes rusted through the floorboards and a backseat full of candy wrappers.

In this disaster, did Ray Midge take to bed and wail and whimper and dream of release? Did he ingest medicine to the limit and press ice packs to his body? Did he speak of his plight to any who would listen? Did he explain in detail just how, where, and in what degree he was suffering?

No. Ray got a map and traced the route Guy Dupree and Norma were following by examining the charges against his credit card. Relying on past courses in geography (no knowledge is impertinent to the wise man), he came to a conclusion about what he must do. Having no cash on hand, he gathered his government bonds, gassed up the sorry Buick, put a sign on his door to let all know he was gone for a spell, and took off for Mexico.

Ray Midge was suffering. He was encased in a catastrophe akin to any number of literal casts enclosing any number of living limbs, but he was not sitting still. He was waiting for no man’s aid. He was obeying the crucial law of nature articulated by Sir Thomas Browne in the seventeenth century. He was restless, and he was moving.

Inspired, I rose from bed and walked, ice pack cradling my cast, head buzzing with hydrocodone. In my free hand I carried Portis’s novel, as I moved in the restless motion of all creatures, and I found solace there. Dr. Reo Symes, Portis’s defrocked physician and the owner of a disabled bus called the Dog of the South, gave me direction, too, as he lectured Ray about the greatest writer in civilization, John Selmer Dix, M.A., a philosopher who urged opposing extremes in all situations.

Do not be afraid to act, wrote Dix, but do not act simply to act. Spend without thought for tomorrow, but save always for the rainy day. Take an action, then oppose that action, and stay still and keep on the move.

In my state of cast capture, of restlessness without destination, I found Ray Midge’s adventures to be the precise medicine I needed. It did not cure; it made no false promises. Ray Midge knew that to exist is to suffer confinement and no promise of change. Like Ray, I found that I could bear to wait for the morning to come.

An old clown gave Ray Midge a card at one point. Printed on it was the advice, “Watch out for the FLORR.” That’s what I had to do in my imprisonment. Don’t fall down again. Keep moving. Obey the law which governs all creatures, great and small, sick and well. Watch out for the Florr.

Throughout the journey Ray follows that advice. He gets Norma back and takes her home to Little Rock, and he’s satisfied in his apartment lined with books. Of course, she soon leaves him again, this time for Memphis, to live on her own. But that is fitting and proper, I know. Nobody comes back from Memphis.

Gerald Duff has taught at Vanderbilt University in Nashville and served as academic dean at Rhodes College in Memphis. His most recent novel is Playing Custer; a new edition of That’s All Right, Mama: The Unauthorized Life of Elvis’s Twin will be published this year.