How I Fell for French Poetry

Knoxville poet Marilyn Kallet confesses her love affair with translation

My Facebook status might say, “It’s complicated.” In the beginning, it wasn’t. As a first-year student in 1964 at Jackson College, Tufts University, I took French poetry with Madame Georgette Pradal. She was from the South of France, had trained as an actress in Paris. Her forte was tragedy. Her husband Pierre had died young; she sighed notes of grief into every poem. When she recited Racine’s Phèdre, she transformed herself into the demonic older woman with a forbidden love, the character whose hair and jewelry had become “vain ornaments” that weighed her down.

Madame was strikingly beautiful. Long dark hair wound around her head; her lipstick gleamed red, perfect. When we arrived at the Modern section of our syllabus, in spring, 1965, it was warm enough for the buds to burst forth outside the open windows of Medford Hall. Madame Pradal performed Baudelaire’s poems, and my fate was sealed. All of us students fell in love. But were we in love with our professor, with poetry, or with the French language?

Madame was strikingly beautiful. Long dark hair wound around her head; her lipstick gleamed red, perfect. When we arrived at the Modern section of our syllabus, in spring, 1965, it was warm enough for the buds to burst forth outside the open windows of Medford Hall. Madame Pradal performed Baudelaire’s poems, and my fate was sealed. All of us students fell in love. But were we in love with our professor, with poetry, or with the French language?

Sometimes I felt dizzy when Madame performed poetry. After class, I sat outside on the lawn, revisited Baudelaire. Were there chemicals in my book that made me swoon––something in the paper of Les Fleurs du Mal that affected my senses? I licked a page to see if it had LSD on it. How did poetry achieve the effect of making me feel drunk? (Consult Baudelaire’s prose poem, “Enivrez-vous”, “Stay Drunk!”)? This obsession with the music of poetry and impact became my lifelong study.

I took the opportunity through Tufts to study at the Sorbonne for my junior year. A rough year! I could recite Racine and Baudelaire, but that didn’t help when I tried to buy an egg (oeuf, like “oof!”in an American student’s mouth) at the market. Once, an elderly woman on a street corner spat on me when I asked her for directions. Luckily I had a kind professor of prononciation at the Sorbonne’s Cours de civilisation. When I read verses aloud to him in French, he always replied, “Ça commence à se mettre en place, Mademoiselle.” “It is beginning to sort itself out.”

Translation is always “beginning to sort itself out.” When one is translating poetry––that ineffable construction where syllables count and sounds rule––the resulting poem in English will never be perfect. One aims for accuracy, but idioms in another language can be tricksters. Perhaps more important than accuracy is the translator’s skill in recreating tone and musicality in American English that offer at least hints of the original. The translator tries to be transparent, to become a medium for the French poet. On a good day, the translator possesses Keats’s “Negative Capability,” that chameleon-like ability to “be inside of uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts”––to live inside a different language without damaging the original intent. For my money, the best translator of Baudelaire is still Wallace Fowlie. His English versions are clear, almost plain; he doesn’t embellish. The worst versions are by Edna St. Vincent Millay, whose verses turn a dangerous French poet into a doily.

When I returned to Tufts in 1966, a young man who wanted to date me gave me a copy of Paul Eluard’s Derniers poèmes d’amour (Last Love Poems). I stood in the doorway of my room at the French House and read the poems to myself, heard them in English as I was reading French. Eluard seduced me with his love songs. Years later, in the ‘70s, I wrote down the translations, and L.S.U. Press accepted the manuscript for publication. Hobart & William Smith Colleges, where I was teaching, sent me to Paris to research Eluard. I met Eluard’s publisher, Lucien Scheler, in his apartment near l’Opéra. Scheler had hidden Eluard and his wife Nusch from the Nazis during the Occupation. He showed me Eluard’s writing paper––slick blue sheets that the poet had composed on with felt-tipped pens. Surrealist Eluard must have wanted the feeling of glide, of dream. That’s how his songs first entered my brain and body.

When I returned to Tufts in 1966, a young man who wanted to date me gave me a copy of Paul Eluard’s Derniers poèmes d’amour (Last Love Poems). I stood in the doorway of my room at the French House and read the poems to myself, heard them in English as I was reading French. Eluard seduced me with his love songs. Years later, in the ‘70s, I wrote down the translations, and L.S.U. Press accepted the manuscript for publication. Hobart & William Smith Colleges, where I was teaching, sent me to Paris to research Eluard. I met Eluard’s publisher, Lucien Scheler, in his apartment near l’Opéra. Scheler had hidden Eluard and his wife Nusch from the Nazis during the Occupation. He showed me Eluard’s writing paper––slick blue sheets that the poet had composed on with felt-tipped pens. Surrealist Eluard must have wanted the feeling of glide, of dream. That’s how his songs first entered my brain and body.

In 2005, Joe Phillips at Black Widow Press asked whether I would like to revisit my translations. I was thrilled! For years I had obsessed about improving them. Yes, I had heard the poems whispered in English, but whispers can be misunderstood. I knew I could do better. Composer Brian Bevelander has set those translations into classical songs. Readers ask my permission to use the English versions in wedding vows.

My second book of translations was Péret’s Le grand jeu (The Big Game). His volume leapt into my hands from a book display in the Latin Quarter. Péret the Surrealist never compromised. His poems are whacky, subversive. He had a compulsion about spitting on priests in Paris, and would cross the street to spit on one. Once, I made the mistake of taking Le grand jeu to Mount St. Francis in Indiana, where I regularly go for writing retreats. I left Péret’s book and pages of translation open on my desk, fell asleep. When I awakened, the book and my pages were drenched. The window was shuttered tight. Yep, Benny had been there, dissing the Franciscans! If Eluard is the gift for weddings, Péret is perfect for divorce!

Soon I found myself searching for a woman poet to translate. Every spring I teach a poetry workshop in Auvillar, France, for the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and then I go to Paris to peruse bookstores and meet with writers. For years I found few French women poets in any bookstore. I was elated in 2007 to discover an issue of Two Lines: A Journal of Translation, with a poem by Parisian poet Chantal Bizzini, “

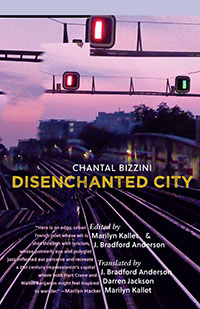

Work on Disenchanted City proceeded slowly. I invited Brad Anderson to help translate Chantal’s manuscript. I learned that he had been one of Chantal’s students in Paris. She teaches independent studies for Stanford University and leads students through hidden corners of Paris. Brad has been kind, meticulous in his work, a dream to collaborate with. And I invited one of my former grad students, Darren Jackson, to translate with us. Darren had lived in France, married a French psychologist, and had created excellent translations of poetry by Michaux. (His translation of Michaux’s Life in the Folds will be out in 2016 from Wakefield Press.)

My co-translators have helped to make Chantal Bizzini’s Disenchanted City a reality. Along the way, Chantal offered suggestions for the English version. She preferred to open the book with a poem about death, but I told her American readers would not swallow that. We compromised by placing “At the Moment of Dying” a little further back. My favorite poems in the book are those suffused with jazz; “Postcard,” dedicated to trumpeter Eric Dolphy, offers one example:

Streaks, colors split into blaring gold,

mystic rays,

pouring from blue-grey clouds,

decompose in rose strips, stretched

thick chalk of reverberating sea…

Chantal notices tiny details of Paris, but she also possesses vision––summoning coastlines of Bretagne, architectural layers of historic Paris and its buildings, ancient, modern. She has translated Hart Crane, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery, Jorie Graham. Her poems are also modernist and collagist. She has been compared to T.S. Eliot, but her gaze is more intimate; her tone offers more warmth. She has been influenced not only by poets, including Walter Benjamin and René Char, but also by modern architects, filmmakers, artists, and photographers.

Chantal and I argued about the epigraph by Propertius. She presented a Victorian translation, but I held firm, translated the lines into the American idiom. We argued about the use of commas. I explained that we use fewer in American poetry. Our contemporary poets shy away from semi-colons, and Chantal’s work is rife with them. “Translate only dead poets from now on!” my husband said, witnessing the arguments.

It was worth the years and literary disagreements to bring Chantal’s volume into print. Her poems are like floating worlds made of cities and shores. Future readers will better understand Paris, with its diverse populations and layers of history, its literary heritage and allure. In addition to being a visual artist, Chantal is also a superb photographer; the cover image of Disenchanted City is a detail from one of her photos.

There is a long tradition in French poetry of the flaneur, the poet who strolls through Paris. Baudelaire was one, and Apollinaire, and Léon-Paul Fargue. And now Chantal Bizzini walks by, flaneuse, always on the move, observant. And now you, dear reader, for the price of a paperback, can stroll les rues de Paris, the coastal cities in Greece, the shores and jazz bars of Bretagne! Bon voyage!

Copyright (c) 2015 by Marilyn Kallet. All rights reserved. Kallet is the author or editor of seventeen books, including The Love That Moves Me (2014); she has translated Paul Eluard’s Last Love Poems (2006), and Benjamin Péret’s The Big Game (2011). Kallet is Nancy Moore Goslee Professor of English at the University of Tennessee, and she teaches poetry workshops for VCCA-France. For information about writing in France, click here.