In a Dark Wood

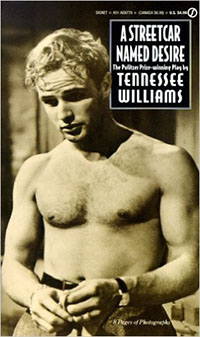

Novelist Adam Ross first opened the closet of adult secrets through the plays of Tennessee Williams, who won a Pulitzer Prize for both A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Like so many American readers, I first encountered Tennessee Williams in high school, both The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire, though Streetcar is the one that really stuck. We used the Signet edition, the one with Marlon Brando, shirtless, on the cover, and it was shocking to behold Brando in his prime, his physique strikingly modern, gym-built long before working out was in vogue. This was 1985, and Brando, familiar to me from his late-career performances—as Vito Corleone, Jor-El, and Colonel Kurtz—was by now a famous recluse, as obstinate as he was obese, spurning Hollywood to live in exile on his private South Pacific island. Rumor had it he’d swelled to nearly 400 pounds.

This narrative bespoke an uncompromising maverick, a genius impossible to work with, a great talent squandered. And yet here on the cover of A Streetcar Named Desire was Brando at his apogee, possessed of a brutish beauty that transcends categories. Back then gay and fag were the worst slurs boys could toss at each other, and yet his allure was so patently undeniable that I recall acknowledging his splendor without any discomfort. It also posed a question any teen could ask any adult: how did you let yourself go?

This narrative bespoke an uncompromising maverick, a genius impossible to work with, a great talent squandered. And yet here on the cover of A Streetcar Named Desire was Brando at his apogee, possessed of a brutish beauty that transcends categories. Back then gay and fag were the worst slurs boys could toss at each other, and yet his allure was so patently undeniable that I recall acknowledging his splendor without any discomfort. It also posed a question any teen could ask any adult: how did you let yourself go?

Reading a play, even Shakespeare, is always an aesthetically limited experience: the text’s magic pales before an onstage performance. No wonder English teachers always “show the movie,” a pedagogical tool that sends ripples of excitement through any classroom the minute students see the TV on its rolling stand: here’s a chance to catch a nap in the dark; it’s like a mini sick day in school!

I was completely unprepared for the impact of Streetcar. Seeing that play at age seventeen was like hearing your parents fight through their bedroom wall: a half-comprehended language recognized, on some pre-cognitive level, as a foreshadowing of adulthood’s complications. Watching the play is to realize that mysterious, unspeakable, often destructive things bind people together. Love, that great enigma, that thing I’d felt intimations of but had yet to experience, can destroy you as easily as it saves you. Can pit sisters against sisters, husbands against wives. I thought growing up meant you gained more self-control, but here were adults behaving like children: tossing radios out windows in a drunken fury; punching out their pregnant wives and then making love to them immediately afterward; perpetrating acts of nearly unimaginable cruelty, denigration, and degeneration while also rescuing each other with heroic acts of kindness. The proximity of these contraries was vertiginous, the suspense unlike any I’d ever experienced—not the plot-driven thrill of an action movie but the drama of a human heart in conflict with itself, as Faulkner put it when he won the Nobel Prize two years after Williams won a Pulitzer for Streetcar.

“You need somebody,” Mitch tells Blanche on their last happy evening together. “And I need somebody, too. Could it be—you and me?” And Blanche, so close to ruin, takes Mitch in her arms, her tacit yes to his tacit marriage proposal as powerful as Molly Bloom’s literal one at the end of Ulysses. “Sometimes,” she says “there’s God—so quickly!”

Becoming an adult seemed as exciting and dangerous to me as walking Central Park at night.

By my late thirties I was married myself and had embarked on a writing career; children were on the way. If adult life is a Tennessee Williams play, mine felt closer to his other Pulitzer-winner than to Streetcar. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is a family drama, and the play’s setting—Big Daddy’s plantation—along with its concerns, are decidedly bourgeois. Its greatness lies in how brilliantly the spiritual is intermingled with the material, the sexual with the practical. The play tells us that sublimation of desire in a capitalist economy is both central to success and the source of all psychological pain and personal regret.

Beautiful, ferocious Maggie prowls Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, trying to get Brick to make love to her again—to reignite the passion between them—but also to keep from losing their inheritance: Big Daddy, now dying, may leave his enormous fortune to his conniving eldest son if Maggie and Brick don’t hurry up and provide the patriarch with an heir. I am side-stepping the play’s remarkable examination of Brick’s repressed homosexuality and its attendant shame, but this is also a story about living up to your potential. About getting ahead by letting go, securing what you believe is yours, all the while keeping the home fires burning. It’s a tricky business, but so much of America’s business is just that. We want it all, and for me, an aspiring novelist chasing dreams of literary glory while helping to support a young family, the balancing act between personal ambition and familial responsibility seemed as daunting a challenge as Maggie’s: “What is the victory of a cat on a hot tin roof?” she asks. “Just staying on it, I guess, as long as she can.”

Sometimes the only choice we have is to extend our claws and hold on. Cat ends with the suggestion that Maggie is victorious: Brick and Big Daddy have reconciled, his father will draw up a new, favorable will in the morning, and the couple has repaired to bed. “Oh,” Maggie says to her husband, “you weak, beautiful people, who give up with such grace. What you need is someone to take hold of you—gently, with love, and hand your life back to you, like something gold you let go of—and I can! I’m determined to do it—and nothing’s more determined than a cat on a tin roof—is there? Is there, baby?”

Sometimes the only choice we have is to extend our claws and hold on. Cat ends with the suggestion that Maggie is victorious: Brick and Big Daddy have reconciled, his father will draw up a new, favorable will in the morning, and the couple has repaired to bed. “Oh,” Maggie says to her husband, “you weak, beautiful people, who give up with such grace. What you need is someone to take hold of you—gently, with love, and hand your life back to you, like something gold you let go of—and I can! I’m determined to do it—and nothing’s more determined than a cat on a tin roof—is there? Is there, baby?”

Like Maggie, I, too, refused to let go of the vision I had for both my life and my career. And from the outside, at least, things seemed to have worked out.

By the time I was forty, nearly everybody my wife and I knew had foundered somehow, the victims of a certain species of madness to which we are most vulnerable when we are not yet old but no longer young. There was so much waywardness and affliction surrounding us it suddenly made sense to me why Dante opens The Inferno with these words: In the middle of life’s journey, I came to myself in a dark wood, where the direct way was lost. Our friends got divorced; or had children and then got divorced; or committed adultery and then patched things up (miserably, quietly, desperately). Some of them kept on misbehaving, like people who claim they drive better after a few drinks. Some got addicted to drugs. One, in a drunken fight with her husband, pressed a gun to her own head and nearly shot herself. And for a while there, things could be storm-tossed in my house, too. An enviable few seemed to enjoy smooth sailing—spiritual, financial, matrimonial; they hit the damn trifecta. But who knows what goes on behind closed doors? (One of those ideal couples just split up.) All relationships cycle through deep intimacy and despair, indifference and passion, sleep and wakefulness, until they don’t.

So when I watched Streetcar again not long ago, I found it a far less outlandish experience than I did as a young man. “Adulthood is like that,” I thought. Not always, of course: tragedy’s inevitability pitches Streetcar’s emotions and actions to extremes. Still, we drink too much; marry the wrong person for the right reason or the right person for the wrong one. We can be cruelest to those closest to us; kindest to those to whom we are least beholden. We chase ghosts in strangers’ bodies. Cling to old hurts. Play pretend in age-inappropriate clothes beneath a paper lantern’s colored light. (For what else is Instagram and Facebook?)

We make a mess of it, just like Blanche, a high-school teacher fleeing a scandalous affair with a student, who arrives at her sister’s door having nowhere else to turn. Bit by bit, she’s sold off the family plantation because their parents made no plans for its security, a slow-rolling event that could stand in for the subprime mortgage crisis or any of our country’s other recent recessions. Like so many of the “losers” in today’s rigged economy, Blanche has fallen off capitalism’s tightrope without a safety net. Disenfranchised, damaged, she knows her fading beauty is the one currency left to her, but it requires the male gaze and thereby relies on distortion and deception, obfuscation and illusion.

We make a mess of it, just like Blanche, a high-school teacher fleeing a scandalous affair with a student, who arrives at her sister’s door having nowhere else to turn. Bit by bit, she’s sold off the family plantation because their parents made no plans for its security, a slow-rolling event that could stand in for the subprime mortgage crisis or any of our country’s other recent recessions. Like so many of the “losers” in today’s rigged economy, Blanche has fallen off capitalism’s tightrope without a safety net. Disenfranchised, damaged, she knows her fading beauty is the one currency left to her, but it requires the male gaze and thereby relies on distortion and deception, obfuscation and illusion.

Then, as now, the playing field isn’t level, and Blanche is at a disadvantage. At once fluttering, delicate, and beautiful (Williams describes her as “moth-like” at the play’s outset), poetic and prevaricating, she’s far more romantic than Cat’s Maggie—Blanche would take magic over money any day. She finds herself immediately pitted against her brother-in-law, Stanley. Part predator, part troglodyte (“Meat!” is the first word he utters in the play), and part tyrant, Stanley is a physically and verbally abusive man who cares nothing for his sister-in-law’s plight beyond the inheritance—part his, he believes—that she’s squandered. Blanche puts up a good fight, but Stanley has neither time nor sympathy for anyone who might limit his appetites or challenge his superiority, and unlike Blanche, he plays for keeps. “You know what luck is?” Stanley tells his buddies. “Luck is believing you’re lucky…. To hold front position in this rat-race you’ve got to believe you’re lucky.” This, after raping Blanche and breaking her mind.

Yet all hope need not be abandoned.

Blanche, confronted by Stanley’s war buddy Mitch, is brave enough to confess her entire past to him, copping to the lovers she’d taken out of loneliness and desperation, and giving a fuller accounting of the grief she suffered after the suicide of her first husband. She offers Mitch a chance to forgive her the mess she’s made: “I had many intimacies with strangers. After the death of Allan—intimacies with strangers was all I seemed able to fill my empty heart with,” Blanche tells him. “I think it was panic, just panic, that drove me from one to another, hunting for some protection—here, there, in the most—unlikely places—even, at last, in a seventeen-year-old boy.” Mitch understands grief, and she appeals to his empathy: “I was played out,” she continues. “You know what played out is? My youth was suddenly gone up the water-spout, and—I met you.”

Instead of opening his heart, he spurns her.

Still, you have to admire Blanche’s bravery. With Mitch, she would build a bulwark against chaos, madness, and loneliness, a bulwark also known as trust. What an example to any of us who have taken a streetcar named Desire to Elysian Fields only to arrive somewhere unexpected or worse—what an example in courage, to demand love by owning all we have been. That’s a very different approach to life than relying upon the kindness of strangers. That’s asking the people we share our lives with to be adults.

Adam Ross is the author of Mr. Peanut and Ladies and Gentlemen. In February 2016 he was named editor of The Sewanee Review. He lives in Nashville and Sewanee.

This essay is part of the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prize board and the Federation of State Humanities Council in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. For their generous support of the Campfires Initiative, we thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes board, and Columbia University.