In the Land of the Unreliable Narrator

In a new story collection by Junot Díaz, unfaithful men stumble through lives of leave-taking and loss

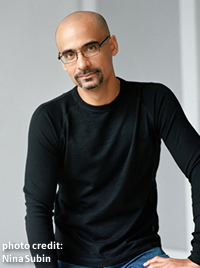

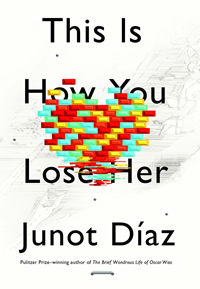

Within a week of its release, Junot Díaz’s new book, This Is How You Lose Her, appeared on The New York Times bestseller list. Rarely does a book of short stories—rarely does literary fiction by a Latino author—generate attention like this. Rarer still are collections that deserve such hype, but in this case, the excitement is well deserved. Díaz, who this week won a MacArthur “genius” grant, is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and his growing legion of fans ought to be well pleased, even thrilled, by the nine dynamic stories in this collection, all told in Díaz’s inimitable style, a voice that is at once profane and profound.

This Is How You Lose Her is Díaz’s second short-story collection. (The first was the critically acclaimed Drown.) This book focuses on betrayal, particularly the havoc wrought by infidelity, and most of the stories question the viability of committed relationships. Biological tendencies combine with the complications of contemporary life to make it a wonder that monogamy works at all for couples. Everybody, these days, can cheat, but in the anachronistic world of this collection, only men exercise the option. They mostly feel terrible about the suffering they inflict upon the women who love them, but when Magda’s characterization bleeds into Alma’s, while Flaca seems a lot like Miss Lora, and the unnamed salcedeña in “The Cheater’s Guide to Love” could be a twin to Magda, the reader has to wonder how deeply the unfaithful lovers in these stories (usually a recurrent character named Yunior) feel for the blur of deceived females.

It would be easy to mistake these stories as a feminist affront. Liberated readers, all aboard the equal-opportunity express heading in any direction, including infidelity, should be irked by the crocodile tears shed here by the bereft boyfriend, whose focus on his own heartbreak tends to eclipse empathy for the women he has wounded. Such readers ought to be exasperated that each female character represents only one of two possible tropes: the faithful and righteous or the scheming and ruthless. Yet these very portrayals emanate from a voice that laments, “She could have caught you with one sucia, she could have caught you with two, but as you’re a totally batshit cuero who didn’t ever empty his e-mail trash can, she caught you with fifty!” The irony of blaming a broken engagement on “sucias” (promiscuous women) clearly locates the reader—whew!—in the land of the unreliable narrator. And slangy wit combined with unexpected eloquence, fresh figurative language, and stunning imagery produce a style powerful enough to win over the most ideologically entrenched and literal-minded reader.

It would be easy to mistake these stories as a feminist affront. Liberated readers, all aboard the equal-opportunity express heading in any direction, including infidelity, should be irked by the crocodile tears shed here by the bereft boyfriend, whose focus on his own heartbreak tends to eclipse empathy for the women he has wounded. Such readers ought to be exasperated that each female character represents only one of two possible tropes: the faithful and righteous or the scheming and ruthless. Yet these very portrayals emanate from a voice that laments, “She could have caught you with one sucia, she could have caught you with two, but as you’re a totally batshit cuero who didn’t ever empty his e-mail trash can, she caught you with fifty!” The irony of blaming a broken engagement on “sucias” (promiscuous women) clearly locates the reader—whew!—in the land of the unreliable narrator. And slangy wit combined with unexpected eloquence, fresh figurative language, and stunning imagery produce a style powerful enough to win over the most ideologically entrenched and literal-minded reader.

Despite the determined focus of these stories, they are about much more than one thing, and betrayal here is invariably layered with loss and longing. In “The Sun, the Moon, the Stars,” for example, a doomed couple travels to the Dominican Republic, where the narrator visits the cave of Jagua, the birthplace of the Taínos, the indigenous Caribbean people. “Thinking about the beginning is the end,” he observes, reflecting on the historic betrayal that resulted in the extinction of native culture. “The Sun, the Moon, the Stars” recalls “Homecoming with Turtle,” a personal essay by Díaz that describes a similar trip. In both pieces, the narrator feels displaced: his “busted-up Spanish” and material privilege mark him as an outsider in his native country, while his racialized appearance marginalizes him in the U.S. Perhaps that early abandonment of homeland serves as an initiation into a lifelong pattern of leave-taking and loss. In this sense, betrayal is something of an identity-shaping project for these characters.

The final story in the collection, “The Cheater’s Guide to Love,” includes another homecoming. This time, the narrator accompanies a friend who is eager to meet the son he fathered on an earlier sojourn. There, they confront the mind-boggling poverty of the Nadalands, “where there are no roads, no lights, no running water, no grid, no anything, where everybody’s slapdash house is on top of everybody else’s, where it’s all mud and shanties and motos and grind….” This catalog of heartbreaking squalor culminates at the moment when the narrator observes the child purported to be his friend’s son: “He has all these mosquito bites on his legs and an old scab on his head no one can explain to you. You are suddenly overcome with the urge to cover him with your arms, with your whole body.” This desire to connect with the neglected boy, who bears a resemblance to his own young self, expresses a longing to fuse past and present, to erase that first abandonment and to reconcile the rift created by betrayal.

The final story in the collection, “The Cheater’s Guide to Love,” includes another homecoming. This time, the narrator accompanies a friend who is eager to meet the son he fathered on an earlier sojourn. There, they confront the mind-boggling poverty of the Nadalands, “where there are no roads, no lights, no running water, no grid, no anything, where everybody’s slapdash house is on top of everybody else’s, where it’s all mud and shanties and motos and grind….” This catalog of heartbreaking squalor culminates at the moment when the narrator observes the child purported to be his friend’s son: “He has all these mosquito bites on his legs and an old scab on his head no one can explain to you. You are suddenly overcome with the urge to cover him with your arms, with your whole body.” This desire to connect with the neglected boy, who bears a resemblance to his own young self, expresses a longing to fuse past and present, to erase that first abandonment and to reconcile the rift created by betrayal.

“Invierno,” the one story that does not directly address infidelity, depicts Yunior’s early days in the U.S. This difficult adjustment is complicated for the family by the presence of Ramon, the patriarch who has been absent from their lives before this time. The rigid control Ramon exerts over his wife and young sons gives Yunior an early lesson in male privilege, skewing relationship dynamics, preventing the trust that only equal partners can attain. But Ramon’s hyper-masculinity and punishing example do more than constrict Yunior’s boyhood; they also compromise his manhood by generating the fear and instability that fuels his compulsion to betray women who love him.

Still more loss, guilt, and grief ensue when Yunior’s brother Rafa is diagnosed with cancer. Díaz portrays this family tragedy with sardonic, even bawdy wit. As his health declines, Rafa enlists the mercenary Pura to enact vengeance against the family that will survive him. In a series of outrageous maneuvers, Pura commits atrocity after atrocity to exploit the family, and in so doing she enables Rafa to rage against the dying of the light. “Pura” is a horrible and hilarious story in this tour-de-force collection.

Before it was released on September 11, the graduate workshops I teach were abuzz with excitement for This Is How You Lose Her, and last week I spied an already battered copy of the collection on the dashboard of a landscaper’s pickup. The range of Junot Díaz’s appeal is unsurprising given his originality and unsparing honesty. As a writer he connects with a wide variety of readers, even if such a satisfying connection evades poor and benighted Yunior in his search for love.

Lorraine M. López, an associate professor of creative writing at Vanderbilt University, is a widely published author of novels, essays, and short stories. Her most recent book, co-edited with Blas Falconer, is The Other Latin@: Writing Against a Singular Identity.

Junot Díaz will discuss This is How You Lose Her at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books on October 13 at 4 p.m. in the War Memorial Auditorium. All festival events are free and open to the public.