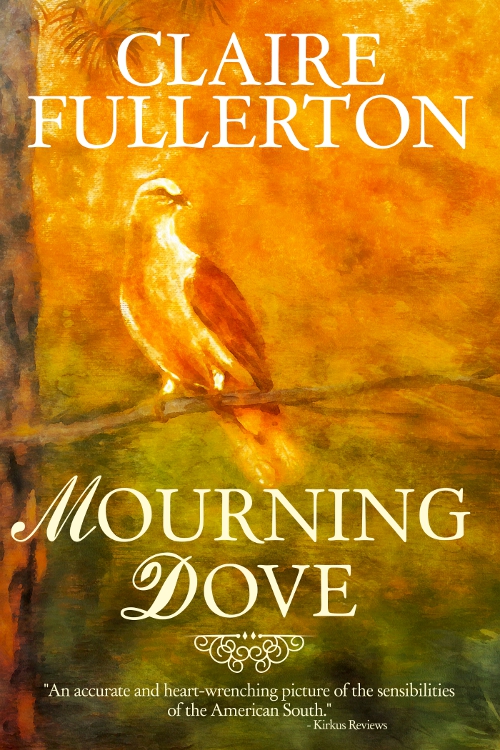

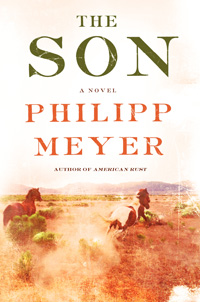

Indians, Cattle, and Oil

Philipp Meyer’s The Son covers all the bases in an epic novel of Texas

The novelist who decides to write a new version of Texas history faces a number of challenges: how to separate truth from legend; where, geographically and chronologically, to begin and end the story; and how to balance the tales of triumph with the sufferings of the vanquished. This terrain has been covered before—in Edna Ferber’s Giant, Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, and James Michener’s Texas, among others—which means that readers have pre-conceived notions about what Texas means. Philipp Meyer appears undaunted by these obstacles. Indeed, the ambition of his new novel, The Son, is nothing less than an attempt to tell the whole story of Texas, from its inception to today.

The novel’s title reverberates in a number of ways, beginning with the birth of its central character, Eli McCullough, on March 2, 1836, the day the Republic of Texas declared its independence from Mexico. Thirteen years later Eli is kidnapped by Comanches and, after surviving months of torture, is slowly integrated into his tribe’s community. Meyer tells this part of the story patiently, allowing readers to see each stage of the young man’s education in the Comanche way of crafting weapons, tracking prey, hunting, fighting, and making love. Eli gradually becomes accepted by the tribe and shifts his allegiance to them, essentially erasing his former existence. They call him Tiehteti-tabo, Pathetic Little White Man, a moniker that changes into a term of endearment as he proves his mettle. He has come to the Comanches at an inopportune time, however: no sooner has he reached the threshold of manhood than the tribe begins to disintegrate from competition with Anglo settlers and from disease. Eli returns to the white world reluctantly and finds that he no longer fits in.

The novel’s title reverberates in a number of ways, beginning with the birth of its central character, Eli McCullough, on March 2, 1836, the day the Republic of Texas declared its independence from Mexico. Thirteen years later Eli is kidnapped by Comanches and, after surviving months of torture, is slowly integrated into his tribe’s community. Meyer tells this part of the story patiently, allowing readers to see each stage of the young man’s education in the Comanche way of crafting weapons, tracking prey, hunting, fighting, and making love. Eli gradually becomes accepted by the tribe and shifts his allegiance to them, essentially erasing his former existence. They call him Tiehteti-tabo, Pathetic Little White Man, a moniker that changes into a term of endearment as he proves his mettle. He has come to the Comanches at an inopportune time, however: no sooner has he reached the threshold of manhood than the tribe begins to disintegrate from competition with Anglo settlers and from disease. Eli returns to the white world reluctantly and finds that he no longer fits in.

The novel’s other two narrative strands follow Eli’s sensitive son Pete, born in 1870, and his great-granddaughter Jeanne Anne, who is born in 1926 and completes the family’s transition from cattle ranchers to oil tycoons. Together the three story lines stretch out over 160 years and cover an impressive array of Texan cultural history. Eli is conscripted into the Texas Rangers and later the Confederate Army. Pete witnesses the murder of the neighboring family, the Garcias (Eli’s long-time rivals), and watches impotently as the Garcia estate is subsumed into the McCulloughs’. He later abandons his family in favor of his love for the sole surviving Garcia, a match that requires them to leave Texas and settle in Mexico City. Jeanne Anne rides the Texas oil boom to wealth and prominence, leading a privileged life in the tony River Oaks section of Houston. The novel begins with Eli on horseback and ends with Jeanne Anne on a Gulfstream jet.

Along the way, Meyer punctures many of the myths of Texas, including the notion that it represented a meritocracy, where skill and determination, rather than birth and privilege, were all that mattered. In fact, class divisions remained resolutely intact, even in the lawless cattle lands of South Texas. Upper-class Texans didn’t even want independence from Mexico: “Let the records show that the better classes, the Austins and the Houstons, were all content to remain citizens of Mexico so long as they could keep their land,” Meyer writes.

Along the way, Meyer punctures many of the myths of Texas, including the notion that it represented a meritocracy, where skill and determination, rather than birth and privilege, were all that mattered. In fact, class divisions remained resolutely intact, even in the lawless cattle lands of South Texas. Upper-class Texans didn’t even want independence from Mexico: “Let the records show that the better classes, the Austins and the Houstons, were all content to remain citizens of Mexico so long as they could keep their land,” Meyer writes.

The Son makes clear that the settlement of Texas—of South and West Texas, in particular—came at a high price, not merely for the indigenous peoples but for the land itself. Meyer’s descriptions are rich with Texas’s flora and fauna; the land, whose deterioration his characters witness with melancholy, was once rich and diversified. Eli observes firsthand how massive cattle operations like his own have destroyed the countryside. “I don’t have to tell you what this land used to look like,” he says to Pete. “And you don’t have to tell me that I am the one who ruined it. Which I did, with my own hands, and ruined forever. You’re old enough to remember when the grass between here and Canada was balls high to a Belgian, and yes it is possible that in a thousand years it will go back to what it once was, though it seems unlikely.”

The Comanches, too, feel nostalgia for better days. Eli’s mentor, Toshaway, recalls when their tribe ruled the land. “I wish you had been born twenty years ago, Tiehteti, because those were the real days. The buffalo wolves used to follow us on our raids because they knew they’d get something to eat,” he says. “But perhaps those times will return.” This novel serves as an elegy for all the varieties of glory that the peoples of Texas have seen vanish.

The land may once have been beautiful, but Meyer does not idealize life on the frontier for the white settlers or for the natives. He certainly does not downplay or euphemize the violence. In the opening sequence, Eli’s family is captured by the Comanches, and he is forced to watch while the raiding party takes turns raping his mother and sister. “Later, when they led us out, I saw a body with its breasts cut off and its bowels draped around,” Eli says. “I knew it was my sister but she no longer looked like herself.”

Through Eli, Meyer attempts to correct misrepresentations of Native Americans, portraying their blood lust with the same objectivity that he treats the outrages perpetrated by whites. The natives torture captives as a form of public entertainment; Eli kills on sight any man who rides a horse through his property, on the presumption that he is a cattle thief. The Comanches see themselves as more virtuous, and the white characters are equally adept at justifying their atrocities.

Legends of the cowboys get skewered, as well. Though the image of the cowboy figures prominently in Texas’s identity, the ascendancy of ranching culture actually lasted just a short time. Jeanne Anne’s brother Jonas explains that their father is deluded when he refers to their estate as the “Frontier with a capital F. I told him that the frontier had closed before he was even born, and then he would lecture me about tradition we were carrying on. I would tell him there was no tradition, there could be no tradition for a thing that had lasted only twenty years.”

Meyer, a Baltimore native, studied writing at the University of Texas and has settled in the state; he seems to have absorbed it thoroughly. Readers who have endured Texas summers will immediately recognize his description of the weather: “It was the time of year the heat becomes its own entity, a creeping misery. No. It was like a sledgehammer on the head of a steer.” The story contains cameo appearances from famous Texans like H.L. Hunt and LBJ, but for the most part Meyer lets his fictional creations convey his rendition of the state’s complicated past.

At times he seems too eager to show off his research, dropping into the story long lists of plant names or descriptions of historical developments that slow down the narrative flow, and his characters deliver lectures that sometimes feel stilted. But such moments of pedantry do little to mar this involving and moving novel. Meyer’s work deserves its place among the great epics of Texas; even more, his vision of the state will change the way readers understand and judge its history and its folklore.

Philipp Meyer will discuss The Son at Parnassus Books in Nashville on June 25 at 6:30 p.m.