Intolerable to Fate

Nobody gets off scot-free in Tim Johnston’s haunting story collection, Irish Girl

“Dirt Men,” the lead story of Tim Johnston’s Irish Girl, opens with an image of men clearing debris from an old auto salvage dump to make way for a parking lot. The banal work abruptly halts when, to the astonishment of the titular workers, a bucket loader emerges from the earth holding the body of a girl. It’s a startling discovery, and Johnston describes it with haunting tenderness: “All of her in there, tucked into the same shape, the same egg of earth, in which she’d been buried—just the arm extending, the hand open, trying to reach for something, someone.”

This moment, despite its faint resemblance to the opening scene of a television police procedural, triggers an unexpected investigation into a history that has nothing to do with the dead girl or how she came to her violent end. Instead, it has everything to do with the men who found her there: their own secrets, and the unspoken, simmering conflicts between them. It also serves as a thematic signpost for a collection of stories preoccupied with a litany of the most dreadful fears in the lives of mostly common, plainspoken, contemporary Middle Americans—fears that are always intimately connected to something long submerged but never forgotten. The persistent apprehension in Tim Johnston’s Irish Girl calls to mind a familiar warning from Faulkner: “The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.”

The tragedies that pile up in Irish Girl read like a compilation of the best of Oprah and Nancy Grace: fatal car accidents; school or office shooting sprees; mothers and fathers lost to cancer; and, worst and most predictably of all, the disappearance and abuse of children. And yet Tim Johnston’s aim seems less to exploit these lurid twenty-first century American Gothic nightmares than to use them as vehicles for unearthing the formidable anxieties underlying even the most honest, decent, and faithful lives. For Johnston’s characters, buried complications—like the abandoned body of a murdered girl—wait to be lifted to the surface by chance and circumstance. “Ain’t nobody gets off scot-free,” one of the dirt men says, and the stories that follow aim to prove him right.

The tragedies that pile up in Irish Girl read like a compilation of the best of Oprah and Nancy Grace: fatal car accidents; school or office shooting sprees; mothers and fathers lost to cancer; and, worst and most predictably of all, the disappearance and abuse of children. And yet Tim Johnston’s aim seems less to exploit these lurid twenty-first century American Gothic nightmares than to use them as vehicles for unearthing the formidable anxieties underlying even the most honest, decent, and faithful lives. For Johnston’s characters, buried complications—like the abandoned body of a murdered girl—wait to be lifted to the surface by chance and circumstance. “Ain’t nobody gets off scot-free,” one of the dirt men says, and the stories that follow aim to prove him right.

Johnston, a native Iowan, situates most of Irish Girl in distinctly Midwestern locales, populating the stories with a cast of characters who, regardless of their assorted peculiarities, seem purposefully “typical”: construction workers, mechanics, home-supply-store employees; lawyers, teachers, students. Each of his protagonists is confronted with the specter or present reality of some awful loss, and each is stunted or stymied in some way by regrets, past indiscretions, or moments of misunderstanding which they find themselves unable to escape or reconcile.

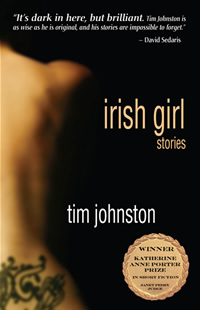

The title story, winner of a 2003 O. Henry Prize, is not, as the cover photograph suggests, a paean to some ginger-haired Gaelic beauty with a seductively situated tattoo, but an effort to reconstruct a distant heartbreak. A man named Charlie looks back into his childhood, mentally unpacking the minor incidents that served as signs and signals he was wary enough to notice but too young to comprehend on the road to his family’s dissolution. Johnston gently and skillfully evokes the guilt and confusion of a child forced far too early to choose sides. The Irish girl, it turns out, is a minor character; like the dead girl of “Dirt Men,” she is significant only for her role in triggering a wellspring of emotion in the story’s seemingly detached protagonist. The point of the story isn’t what happens so much as how the grown-up Charlie engages the problems of perception that cloud his childhood memories. “Everything after that,” Johnston writes, “seems to happen through a cracked window, with Charlie standing outside looking in.”

Irish Girl‘s preoccupation with the impact of the past on the present yields mixed results. At times, the minds of the characters are so immersed in reflection that the present action starts to seem less remarkable than what’s already happened. The dependence on back-story, however essential, leaves some of the narratives feeling unbalanced or incomplete. Similarly, Johnston’s frequent refusal to resolve the tragic or violent events at the center of his stories can make these elements seem like red herrings. Chekhov’s rule that one should never put a gun on stage unless someone’s going to shoot it occasionally comes to mind. The few guns that actually appear in the present action of these stories are eventually fired, but only to shoot at harmless deer. They elevate tension without providing resolution.

Irish Girl‘s preoccupation with the impact of the past on the present yields mixed results. At times, the minds of the characters are so immersed in reflection that the present action starts to seem less remarkable than what’s already happened. The dependence on back-story, however essential, leaves some of the narratives feeling unbalanced or incomplete. Similarly, Johnston’s frequent refusal to resolve the tragic or violent events at the center of his stories can make these elements seem like red herrings. Chekhov’s rule that one should never put a gun on stage unless someone’s going to shoot it occasionally comes to mind. The few guns that actually appear in the present action of these stories are eventually fired, but only to shoot at harmless deer. They elevate tension without providing resolution.

But even the less successful stories in Irish Girl are redeemed by Tim Johnston’s consciousness of thematic unity, his finely wrought characters, his deft and accessible prose, and his touch for memorable details that repay our attention: an autographed Michael Jordan poster on the wall behind a therapist’s desk, a dragonfly tattoo on the hip of a runaway sister, a wolfman doodle on notebook paper, a maimed statue of the Virgin Mary.

Johnston’s first book, Never So Green, was marketed as a young-adult novel, and though the stories in Irish Girl deal with ostensibly “grown-up” concerns, their crises all revolve, directly or indirectly, around imperiled children. Johnston’s insight into the minds and problems of adolescence remains a formidable strength, particularly in “Irish Girl” and “Things Go Missing,” perhaps the cleverest and most appealing story of the collection. In it, a teenaged girl describes her short-lived career as a burglar and her road to recovery through the aid of a sympathetic, chain-smoking counselor. “As for hide-a-key rocks: Easter eggs are harder to spot,” the precocious Josephine dryly explains. “As for watch-dogs: even the meanest go to pieces at the first taste of Oreo.” Explaining away her progressively brazen home invasions, Jo remarks that “almost anything, in time, can get to seem like nothing.” The comment is transparently disingenuous: Jo has lost her mother to a car accident, and her sister (the bearer of the dragonfly tattoo) has run away from home. Her father consoles himself with obsessive remodeling projects, leaving young Jo to find her own outlets.

Like all of Johnston’s characters, Jo is haunted by the past, by the disappearance of things once loved. Recalling the tattoo on her vanished sister’s hip, she says, “It was like touching something you weren’t ever supposed to touch, like a famous painting, or a dead person, or your own heart.” Throughout the collection, characters are compelled, again and again, to touch the forbidden, sometimes against their will, already mindful of the consequences. The cruelty of the past and the perils of the present intrude upon them regardless of their readiness or their circumstances. While anything may get to seem like nothing for a while, sooner or later we will all be made to pay for our sins—or for our innocence, which may be all the more intolerable to fate.

Tim Johnston will appear at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on May 6 at 7 p.m., and at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on May 7 at 1 p.m.