Kindred Souls of Knoxville

Singer-songwriter-poet-playwright R.B. Morris orbits in the literary gravity of James Agee and their shared city

R.B. Morris recently received a phone call from his longtime friend and sometime touring partner, the legendary folk singer Steve Earle. Both have published books of poetry as well as music, and both share a deep interest in the writer James Agee. Earle explained that he had been asked to write a forward for a new edition of A Death in Family, Agee’s Pulitzer-winning novel based on his own boyhood in the Ft. Sanders section of Knoxville, the place—not coincidentally—where Morris grew up.

“They should be getting you to do this,” Earle said, “but they’ve asked me. So I want to ask you some questions.”

The conversation that followed resulted in an introduction, published last month, in which Earle admits he didn’t hear of Agee until 20 years after he came to Nashville to launch his recording career, when he finally read “the greatest writer the state has ever produced.” The reason for the delay, as he explains in the introduction: “I was hanging out in the wrong part of Tennessee. James Agee came from Knoxville, some two hundred miles to the east. In another time zone. Another world. Knoxville is where the Old South ends and the rustbelt begins.”

The conversation that followed resulted in an introduction, published last month, in which Earle admits he didn’t hear of Agee until 20 years after he came to Nashville to launch his recording career, when he finally read “the greatest writer the state has ever produced.” The reason for the delay, as he explains in the introduction: “I was hanging out in the wrong part of Tennessee. James Agee came from Knoxville, some two hundred miles to the east. In another time zone. Another world. Knoxville is where the Old South ends and the rustbelt begins.”

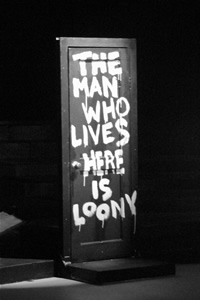

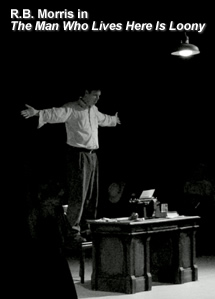

Knoxville’s “other world” is what holds and fascinates R.B. Morris, as it did Agee before him. This fascination may explain why Morris has devoted much of his adult life to celebrating and seeking wider recognition for Agee’s work. Morris has written and performed a one-act play about Agee, The Man Who Lives Here is Loony. His songs contain both implied and direct references to Agee’s work, and he was one of the first local artists to pressure Knoxville—a city that Morris says has often been a bit “ahistorical” concerning its own cultural heritage—into recognizing its native son: Morris was instrumental in the founding of James Agee Park in 2005 and in launching an Agee centennial celebration this month.

Morris speaks as he sings, in a melodious baritone that carries just a hint of mountain twang. “The geography here is mountainous, and the Tennessee River runs right through town,” he says of the Knoxville mystique, “so you’ve got a nice lovely geographic setting. You’ve got a lot of mountain music—old-timey music, gospel music—and in many ways this is one of the first places that it started to take root, one of the first towns.” Like many Southern singers, Morris first encountered such music as a child in church: “So as I was growing up, I was getting, like most kids in America, doses of rock and roll, and doses of popular music.”

Local tensions between conservative churchgoers and bohemian artists made [Morris] pay closer attention to both the musical and literary legacies of the city.

But because Knoxville is also home to the University of Tennessee, Morris felt the influence, from an early age, of people from around the world. He believes it was this mix of two worlds—one cosmopolitan, educated and diverse; the other conservative, unsophisticated and provincial—that sparked not only his own poetic imagination, but Agee’s before him. As Morris grew older, he became aware of the way the musical mix of the city inspired writers like Agee, Cormac McCarthy, and Nikki Giovanni. Local tensions between conservative churchgoers and bohemian artists made him pay closer attention to both the musical and literary legacies of the city. “It’s a pretty strong tradition on the literary and musical fronts,” Morris says. “Steve Earle said he thought that the Ft. Sanders neighborhood was the greatest in Tennessee, the most intense, the most cutting-edge, because of what it has always been up against.”

Comprising some 50 city blocks near the campus of the University of Tennessee, the Ft. Sanders neighborhood is the most densely populated section of Knoxville. It was the site of a bloody Civil War battle during the siege of Knoxville in November 1863, and is a neighborhood that at times seems to both celebrate and ignore its rich history. For example, earlier this year, archeologists discovered some original artillery positions from the battle at the construction site of a new sorority village. The discovery was noted and remarked on, but it did not affect the planned construction.

Morris first became aware of Agee long before he read anything the writer had produced. In 1962, when Morris was not much older than Agee’s character at the opening of A Death in the Family, Hollywood came to Knoxville to shoot All the Way Home, an adaption of the novel starring Gene Simmons and Robert Preston (not to be confused with a 1981 TV adaptation of the same name, which starred Sally Field and William Hurt). Scenes were filmed in the Ft. Sanders neighborhood and at the nearby rail station. Morris’s father, who worked for the railroad, would come home and describe the scenes he had watched from his window on the second floor of the train station. Later Morris’ family attended the premier of the movie in Knoxville, the memories of it leaving a nearly magical impression.

Morris first became aware of Agee long before he read anything the writer had produced. In 1962, when Morris was not much older than Agee’s character at the opening of A Death in the Family, Hollywood came to Knoxville to shoot All the Way Home, an adaption of the novel starring Gene Simmons and Robert Preston (not to be confused with a 1981 TV adaptation of the same name, which starred Sally Field and William Hurt). Scenes were filmed in the Ft. Sanders neighborhood and at the nearby rail station. Morris’s father, who worked for the railroad, would come home and describe the scenes he had watched from his window on the second floor of the train station. Later Morris’ family attended the premier of the movie in Knoxville, the memories of it leaving a nearly magical impression.

Morris says he understood, even as a child, that coming from Knoxville and the Ft. Sanders neighborhood had somehow contributed to Agee’s imagination. “That was his early beginnings,” he explains, “so it was important to him and helped to shape him in a lot of ways. Later he spent most of his time in New York and then in Hollywood in that whole milieu, and it was completely different, so I think it always gave him a little bit of a Southern mountain anchor, some other kind of sensibility—small town, I guess you could say—that might have countered all that.”

It’s the same anchor that has held Morris. After reading A Death in the Family, Morris moved on to Agee’s reporting masterpiece, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which is still considered not just a moving portrait of Southern tenant farmers during the Depression, but one of the most influential works of creative nonfiction this country has produced. The discovery in turn led Morris to Agee’s poetry, which won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition when he was just past college (Morris calls him a “hillbilly at Harvard”), and then, finally, to Agee’s film criticism and screenplays, still studied by filmmakers on both coasts.

It’s the same anchor that has held Morris. After reading A Death in the Family, Morris moved on to Agee’s reporting masterpiece, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which is still considered not just a moving portrait of Southern tenant farmers during the Depression, but one of the most influential works of creative nonfiction this country has produced. The discovery in turn led Morris to Agee’s poetry, which won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition when he was just past college (Morris calls him a “hillbilly at Harvard”), and then, finally, to Agee’s film criticism and screenplays, still studied by filmmakers on both coasts.

This diversity of output was seen by early critics as a sign of profligacy, Morris explains. Some thought Agee should have written more fiction and stayed away from journalism, or written more poetry and stayed away from Hollywood. They tended, also, to view Agee as a young man who wasted his talent through bouts of alcoholism. “The first story was more how he had ‘wasted’ himself,” says Morris, “But I’m affected by the fact that a writer can diversify that much. And in recent years, that’s been the story about Agee. In the end, the story became, ‘Here’s a very modern writer who can take his vision and apply it to any medium that he worked in. He had a great vision, and he had much to say in all those various media.'”

Like Agee during his most prolific years, Morris tends to garner more praise and recognition from peers than from the public at large. Lucinda Williams, with whom Morris has collaborated and toured, has called him the “greatest unknown songwriter in America.”

The house where A Death in the Family was set was torn down nearly fifty years ago, and Agee’s birthplace was torn down a few years later. But a decade ago, Morris was instrumental in getting the University of Tennessee to donate a plot of land about a block from where the novel was set to become a park commemorating the author. He formed an Agee Park Steering Committee and over the course of the next few years gradually found enough private support to get the city behind the park, after performing many local benefit concerts for the cause. The park was dedicated in April 2005, amid a city-wide Agee celebration.

Morris, 57, taught younger writers about Agee as Writer in Residence at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville from 2004 to 2008, and he continues to find new facets in the author’s work. He is “fascinated” by Chaplin and Agee, a 2005 book by John Wranovics, describing Agee’s efforts to discover a new way of communicating in film—much as he did in journalism with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—while collaborating with the actor Charlie Chaplin. Morris has also been drawn to Agee’s articles and essays on the rise of the Nuclear Age, beginning with an essay Agee wrote for Time magazine after the bombing of Hiroshima.

Like Agee during his most prolific years, Morris tends to garner more praise and recognition from peers than from the public at large. Lucinda Williams, with whom Morris has collaborated and toured, has called him the “greatest unknown songwriter in America.”

Like Agee during his most prolific years, Morris tends to garner more praise and recognition from peers than from the public at large. Lucinda Williams, with whom Morris has collaborated and toured, has called him the “greatest unknown songwriter in America.”

“That was very nice of her to say,” Morris says. “I can identify with that ‘unknown’ aspect for sure. The music business is a whole other world, another entity, beside a working writer building a body of work over a lifetime. I’ve dabbled in the music business some, but I’m not active enough. And I’ve perused other mediums—much like Agee in that regard, I guess.” While Morris claims he is “always” working on the next album, he is also completing two plays and a new book of poetry, along with critical essays on Agee and other writers.

“I would love to set him down and be done with him, and I do periodically,” Morris says of the writer who has loomed so large in his life, “but he has so many dimensions and so much to say. He’s very much a modern man, a modern writer, and so I continually have to come back to him and check out the different dimensions that he brings. I think that for anyone who is interested in American literature and American writing, in the new journalism and how it expands into the other media such as film, Agee is required reading.”

Beginning Friday, October 23, and continuing through Sunday, November 22, R.B. Morris will appear in Knoxville at several events honoring James Agee’s 100th birthday. The full schedule is available online as a PDF document at http://web.utk.edu/~english/news/AgeeSchedule.pdf.