Learning to Speak Silence

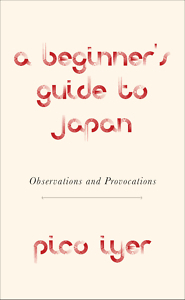

Pico Iyer’s observations and provocations about Japan leave quiet spaces for the reader’s voice

It’s easy to imagine a book titled A Beginner’s Guide to Japan opening with a quotation from a Japanese writer, or perhaps with a few lines from a Westerner saying something pithy about the country. But Pico Iyer has chosen to begin with a sentence from French philosopher Simone Weil: “Attention, taken to the highest degree, is the same thing as prayer.”

Of course, anyone who has read Iyer’s thoughtful and nuanced travel writing won’t be expecting a “Top Ten Ramen Bars in Tokyo” type of guide. Still, the Weil quote makes clear that what lies ahead will explore attention itself as much as it will explore Japan. “I’ve been living in western Japan for more than thirty-two years and, to my delight, I know far less than when I arrived,” Iyer writes in the book’s first pages. “These are simply provocations, opening lines designed to quicken you to better comebacks of your own.”

Most chapters in A Beginner’s Guide to Japan are filled with interlinked observations around a theme, ranging from love hotels to crowds to Japanese baseball. Many chapters contain sections that are only a paragraph or so long, leaving plenty of empty space on the page. As I continued to read, all that empty space began to suggest to me a kind of silence written by Iyer onto the page, a silence the reader was expected to pay attention to.

Maybe I felt this way because I recently moved to Japan and read most of Iyer’s book in a coffee shop in Tokyo on one of my first mornings in the country. An instrumental version of Fiddler on the Roof’s “Sunrise, Sunset” played from the shop’s speakers and nobody around me spoke. I’d never been in a coffee shop that was simultaneously so full of people and yet so quiet. An older man to my left next to me was annotating sheet music. A woman to my right rested her elbow on a book of poetry in English.

“More important than learning to speak Japanese when you come to Japan is learning to speak silence,” Iyer writes. “My neighbors seem most at home with nonverbal cues, with pauses and the exchange of formulae.” Iyer’s words seemed to be a guide not only to the country I had just reached, but to the exact coffee shop in which I was reading his book. Because he so often uses his observations about Japan on the surface to delve into his ideas about what lies beneath that surface, many of his “provocations” seem to apply not only to an outsider in Japan, but to anyone who has ever felt unsure about where they stand and what they see.

“More important than learning to speak Japanese when you come to Japan is learning to speak silence,” Iyer writes. “My neighbors seem most at home with nonverbal cues, with pauses and the exchange of formulae.” Iyer’s words seemed to be a guide not only to the country I had just reached, but to the exact coffee shop in which I was reading his book. Because he so often uses his observations about Japan on the surface to delve into his ideas about what lies beneath that surface, many of his “provocations” seem to apply not only to an outsider in Japan, but to anyone who has ever felt unsure about where they stand and what they see.

One of the primary joys of A Beginner’s Guide to Japan is that it feels like a book where we learn something about the roads the author’s mind takes through time and space, from the classic to the contemporary. In talking about Japanese film, for example, Iyer references the films of the great director Yasujirô Ozu, as well as the 2018 movie Shoplifters directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda. He also mentions plenty of Western works, including Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, John Cage’s 4’33”, and Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation.

Frequently he quotes texts that describe feelings of otherness in different places altogether, including a line from Richard Powers’ novel Galatea 2.2, in which an American narrator living in the Netherlands says, “I was no more than the Foreigner, but even that bit part wound me tighter into the social web than I’d ever been in my country.” Iyer comments on his own meandering process, noting how frequently he has included material about the experience of otherness in countries that aren’t Japan. “Every time I stressed how different Japan was from everywhere else,” he writes, “I found a near-perfect explanation of Japan — in a passage describing somewhere else.”

One of the most profound strengths of A Beginner’s Guide to Japan is the way it winds up emphasizing what it is to feel like a beginner as much as it emphasizes Japan itself. Iyer’s assertions about Japan—those provocations—seem to come not from some obscured authorial voice, but from a specific human being who is trying to begin an intimate conversation with his reader. It’s a conversation that requires not only thought, but a capacity for wonder and close attention.

Lee Conell is the author of Subcortical, a story collection, which won the Story Prize Spotlight Award. Her novel, The Party Upstairs, is forthcoming from Penguin Press. Currently she lives in Tokyo as a Japan-U.S. Creative Artists Fellow. She has taught creative writing at Vanderbilt University and the Sewanee School of Letters.