Letterpressed

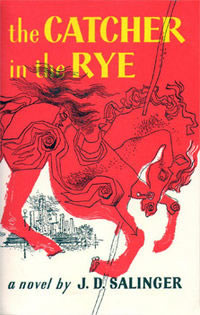

How a Chapter 16 writer’s great-grandmother befriended—and betrayed—J.D. Salinger

Elizabeth Murray, my great-grandmother, met J.D. Salinger through her younger brother, who was the same age as the late novelist. The boys had been high-school classmates at Valley Forge Military Academy, in Pennsylvania. At the time they met, when he was nineteen, Salinger was already writing short stories and obsessed with getting them published. My great-grandmother, who, for forgotten reasons was called Goggy by everyone in the family, lived in New Jersey with her mother and daughter. (Her son, my grandfather, who was also Salinger’s age, was away, serving as a medic in the Army.) From the beginning, Goggy championed Salinger’s writing. In 1941, she introduced him to Oona, the sixteen-year-old daughter of her neighbor Agnes Boulton: Oona’s father was the playwright Eugene O’Neill. Salinger was smitten, but Oona famously ran off to marry the fifty-four-year-old actor Charlie Chaplin. Goggy and Salinger saw each other for regular social visits in the early forties, but then it was wartime, and Salinger soon shipped off to Europe to fight in World War II.

Elizabeth Murray, my great-grandmother, met J.D. Salinger through her younger brother, who was the same age as the late novelist. The boys had been high-school classmates at Valley Forge Military Academy, in Pennsylvania. At the time they met, when he was nineteen, Salinger was already writing short stories and obsessed with getting them published. My great-grandmother, who, for forgotten reasons was called Goggy by everyone in the family, lived in New Jersey with her mother and daughter. (Her son, my grandfather, who was also Salinger’s age, was away, serving as a medic in the Army.) From the beginning, Goggy championed Salinger’s writing. In 1941, she introduced him to Oona, the sixteen-year-old daughter of her neighbor Agnes Boulton: Oona’s father was the playwright Eugene O’Neill. Salinger was smitten, but Oona famously ran off to marry the fifty-four-year-old actor Charlie Chaplin. Goggy and Salinger saw each other for regular social visits in the early forties, but then it was wartime, and Salinger soon shipped off to Europe to fight in World War II.

They never met again, even after the war. Over their long correspondence, Salinger wrote my great-grandmother many letters, thirty-eight of which she eventually sold to the University of Texas. The pages are filed away in the Harry Ransom Center, in Austin, where I flew to read them a couple of weeks after Salinger’s death in 2010. I’d been curious about them for years, but it struck me as impolite to read his private letters while he was alive—I knew, as every other reader in America knew, that he was a fiercely private man.

As physical documents, letters legally belong to the recipient, who has the right to sell them if she wishes, but copyright law protects the contents, which belong solely to the author. These letters, then, can never be published, nor even quoted extensively. In October of 1986, in a case that eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, J.D. Salinger filed a lawsuit against Random House and author Ian Hamilton, blocking the publication of an unauthorized biography, J.D. Salinger: A Writing Life. Claiming copyright infringement and breach of privacy, Salinger’s lawyers argued that the book quoted from seventy of the private, unpublished letters he wrote from 1939 to 1962. Those letters were housed in libraries at Princeton, Harvard, and the University of Texas. Simultaneously, Salinger registered seventy-nine of his unpublished letters, including the ones my grandmother sold, for formal copyright protection.

As physical documents, letters legally belong to the recipient, who has the right to sell them if she wishes, but copyright law protects the contents, which belong solely to the author. These letters, then, can never be published, nor even quoted extensively. In October of 1986, in a case that eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, J.D. Salinger filed a lawsuit against Random House and author Ian Hamilton, blocking the publication of an unauthorized biography, J.D. Salinger: A Writing Life. Claiming copyright infringement and breach of privacy, Salinger’s lawyers argued that the book quoted from seventy of the private, unpublished letters he wrote from 1939 to 1962. Those letters were housed in libraries at Princeton, Harvard, and the University of Texas. Simultaneously, Salinger registered seventy-nine of his unpublished letters, including the ones my grandmother sold, for formal copyright protection.

In 1968, after a twenty-seven-year correspondence, Goggy hired a book dealer to sell Salinger’s letters, along with several manuscripts he’d given her. She needed the money, a sum of less than $10,000, to send her daughter, my great-aunt Gloria, to college. At that point she hadn’t heard from Salinger in five years. To my knowledge, she never heard from him again, but my grandmother says she thinks there may have been an irate telephone call. Either way, she never got another letter. The sale marked the end of their friendship.

What’s surprising is the ending: upon hearing of Goggy’s death in 1979, after a decade of silence, Salinger wrote to Gloria. Dated July 1, 1979, the typed letter’s return address is a post office in Windsor, Vermont. Gloria passed it along to my father, who keeps it in a photo album. Reading it again the week Salinger died, I found it hard to reconcile my odd, familial pride in their friendship with the grim reality that she had, in some very fundamental way, sold him out.

Joan Didion claimed that “[a] writer is always selling somebody out,” but that’s a cynical thought. And it’s certainly not limited to writers.

Joan Didion claimed that “[a] writer is always selling somebody out,” but that’s a cynical thought. And it’s certainly not limited to writers.

Though we never met—Goggy died the year before I was born—from what I’ve learned, Elizabeth Murray had terrible luck, particularly with men. Her first husband died in an airplane crash during World War I, while she was pregnant with their son, John Norris, my grandfather. Her subsequent marriage to a Scotsman ended in divorce (he was abusive), and that relationship was followed by another failed marriage. In between, she got engaged to a wealthy businessman, but they didn’t make it to the altar. Her daughter Gloria suffered from crippling anxiety and agoraphobia, conditions that kept her tethered to Elizabeth. I believe my great-grandmother thought of herself as a smart woman who, somewhere along the line, had gotten taken in by a few real bad deals. In fact, hers were real bad deals. But she had friends, an active social and intellectual life. To pay the bills, she worked, intermittently, as a secretary, but otherwise she wasn’t much interested in money. She was known among friends for her flair and sparkling conversation. She had, as they say, a lot of charisma.

In Goggy, more than twenty years his senior, Salinger found an ardent fan of his work. Reading his letters reminded me of that classic line by Janet Malcolm: “A correspondence is a kind of love affair… [but] it is with our own epistolary persona that we fall in love, rather than with that of our pen pal.” In all thirty-eight letters, Salinger asks Elizabeth only two questions.

It turns out J.D. Salinger was a joker. Excepting the standard “Jerome”s, here are the names he used in signing off the earliest letters to my great-grandmother: Graves Cohen, T. Galente, Sue and Chet Abernathy, Esther, Bernie, Mort, Teddy, Cortez, and j.d.s. In the Austin library, I pored over Salinger’s letters, frequently laughing out loud at his quirky, dry humor; his earnest hunger for a wide, distinguished audience; his particular combination of self-deprecation and egoism. Even in 1941, when he was in the army with no armistice in sight, his need for connection outweighed his desire for isolation.

His letters grew less frequent after the war and during his eight-month marriage to a European woman, trailing off as a string of very fond remembrances and best wishes and the hope, but not the plan, to visit Elizabeth again.

His letters grew less frequent after the war and during his eight-month marriage to a European woman, trailing off as a string of very fond remembrances and best wishes and the hope, but not the plan, to visit Elizabeth again.

I grew up knowing that Goggy’s decision to sell those letters had made Salinger mightily unhappy. Yet, when he got word of her death, he wrote a eulogy, a tribute to her character and role as one of his earliest, most enduring supporters. It’s a gorgeous letter, made more so by the fact that he wrote it knowing that she had sold his others. Despite her betrayal of his confidence, he gave to her daughter more of what had been sold: a final page-length letter that tenderly tips his hat to her as his “astonishingly true and vital and rallying and encouraging friend.”

The kicker: my great-grandmother didn’t actually need to sell J.D. Salinger’s letters; she could have instead sold her engagement ring. It was Gloria who sold the ring, many years later, to buy herself a house. To me, there’s a sadness in Elizabeth’s choice, a diminishment in her decision to make of their relationship anything more than a series of personal exchanges between two people. But Salinger’s tribute, a decade later, is a testament to his enduring gratitude and loyalty to her, nonetheless. I’m sure some people will disagree, but in the end I decided there wasn’t anything wrong with what she did. They outgrew each other; life rolled on. Or, rather, I decided that whatever they had shared over the years belonged to them both. It wasn’t for me to judge. But still, I thought, he let go of her first.

Copyright (c) 2011 by Sarah Norris. All rights reserved. Sarah Norris is a contributing writer to Chapter 16. She lives in Nashville.