Life Without a Manual

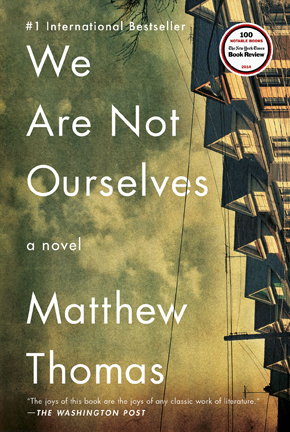

In Matthew Thomas’s debut novel, We Are Not Ourselves, striving Irish Americans learn to improvise when tragedy threatens to derail their dreams

From its opening pages, Matthew Thomas’s debut novel We Are Not Ourselves is about class striving. Eileen Tumulty, born in 1941 to Irish-American parents, learns at too young an age how to take care of her family. Her father, Big Mike, drives a beer-delivery truck and is more concerned with his standing at pubs than with the state of his family. He has a second job tending bar at a local tavern but squanders the income standing drinks for his friends. Eileen’s mother feels trapped in their Queens apartment, a far cry from the American dream she envisioned before emigrating from Ireland, and takes comfort in alcohol. This environment is all the motivation Eileen needs to seek a better life—and avoid romantic entanglements with the working-class lads from Woodside.

With studied determination, she formulates a plan: a nursing degree followed by graduate school in administration. Though she occasionally fantasizes about a life of idle luxury with a rich man, she is fully prepared to realize the American dream on her own. When she meets Ed Leary, a graduate student in neurobiology who shares her working-class background, she thinks she has found the perfect companion to accompany her on the upward journey. After they marry, she supports them while Ed finishes his PhD. Eileen is so close to attaining the grail that she can’t fail to grasp it.

With studied determination, she formulates a plan: a nursing degree followed by graduate school in administration. Though she occasionally fantasizes about a life of idle luxury with a rich man, she is fully prepared to realize the American dream on her own. When she meets Ed Leary, a graduate student in neurobiology who shares her working-class background, she thinks she has found the perfect companion to accompany her on the upward journey. After they marry, she supports them while Ed finishes his PhD. Eileen is so close to attaining the grail that she can’t fail to grasp it.

These sequences occupy the first hundred pages of We Are Not Ourselves. As the rest of this long novel unfolds, the focus shifts subtly from class status to domestic conflict. Thomas offers a portrait of a marriage between two loving partners who nonetheless spar over values. Eileen’s ideal of bourgeois comfort runs up against Ed’s commitment to parsimony. He won’t wear the gold watch she gives him for their engagement; he refuses to indulge her desire to see the Christmas displays on Fifth Avenue; and he begrudges the expense of hosting social functions, even quiet gatherings with professional colleagues.

Worse still, in Eileen’s mind, is Ed’s resistance to career advancement: why does he continually turn down positions at more prestigious institutions or promotion to department chair or dean of the college? She simply doesn’t understand her husband and has no idea where to turn for advice: “[T]hey gave out no manual when you got married, no emergency kit with a flashlight for when the power went out,” she observes. “You had to feel your way around in the dark for the box of matches.”

Their marital squabbles crystallize with the birth of their only child, a son named Connell. Eileen encourages their son to pursue success and thereby raise the family another step on the pyramid, whereas Ed wants Connell to find happiness in the simple pleasures of their Jackson Heights neighborhood. Fixated on their careers and preoccupied with their rivalries at home, neither parent notices as Connell becomes ostracized at school, the chubby nerd whose only social utility is to serve as a punching bag for the cool kids.

Their marital squabbles crystallize with the birth of their only child, a son named Connell. Eileen encourages their son to pursue success and thereby raise the family another step on the pyramid, whereas Ed wants Connell to find happiness in the simple pleasures of their Jackson Heights neighborhood. Fixated on their careers and preoccupied with their rivalries at home, neither parent notices as Connell becomes ostracized at school, the chubby nerd whose only social utility is to serve as a punching bag for the cool kids.

As difficult as the Learys’ marriage is during the first twenty years, matters get much thornier following Ed’s surprise fiftieth birthday party. After faking amusement for the sake of the guests, Ed retreats upstairs. When Eileen gently ribs him about returning to the party, he claims he is exhausted: “I’m tired of standing in front of a bunch of people and being the center of attention. Do you have any idea how much energy that takes? You’re never off. Never. You can never have a bad day.”

Following an unexpected medical crisis, Eileen grasps that her old life is over, that from now on her primary role will be taking care of Ed. Where will her dreams live now? Thomas renders Ed’s disease with moving detail, but the novel doesn’t descend into sentimentality. Eileen’s heartache is leavened by her Irish pragmatism: she keeps her plight in perspective, remembering patients in her hospital who face much worse, and tries to take comfort where she can: “she concentrated on the steadiness of the stars, their transcendence of human sorrow and confusion, the reassurance offered by the unfathomable.”

With long novels, critics often employ the term “epic,” but that designation seems inapt here. We Are Not Ourselves spans decades and depicts these characters in their full human complexity, but the novel is decidedly domestic, its concerns containable within the Leary household. It’s an anti-epic: grand in scale but miniaturist in scope. If it renders, as some reviewers have claimed, the twentieth-century history of the American middle class, it does so metonymically, through the detailed observations of a single family dealing with issues common to us all: work, school, housing, health care, retirement, and death. It also captures the “fugitive joys” of marriage and parenthood, the moments between the disappointments and injuries, that make life bearable—and sometimes sublime.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford University as an undergraduate. He later returned to Austin, where he earned a Ph.D. in modern fiction from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.