Longings so Large

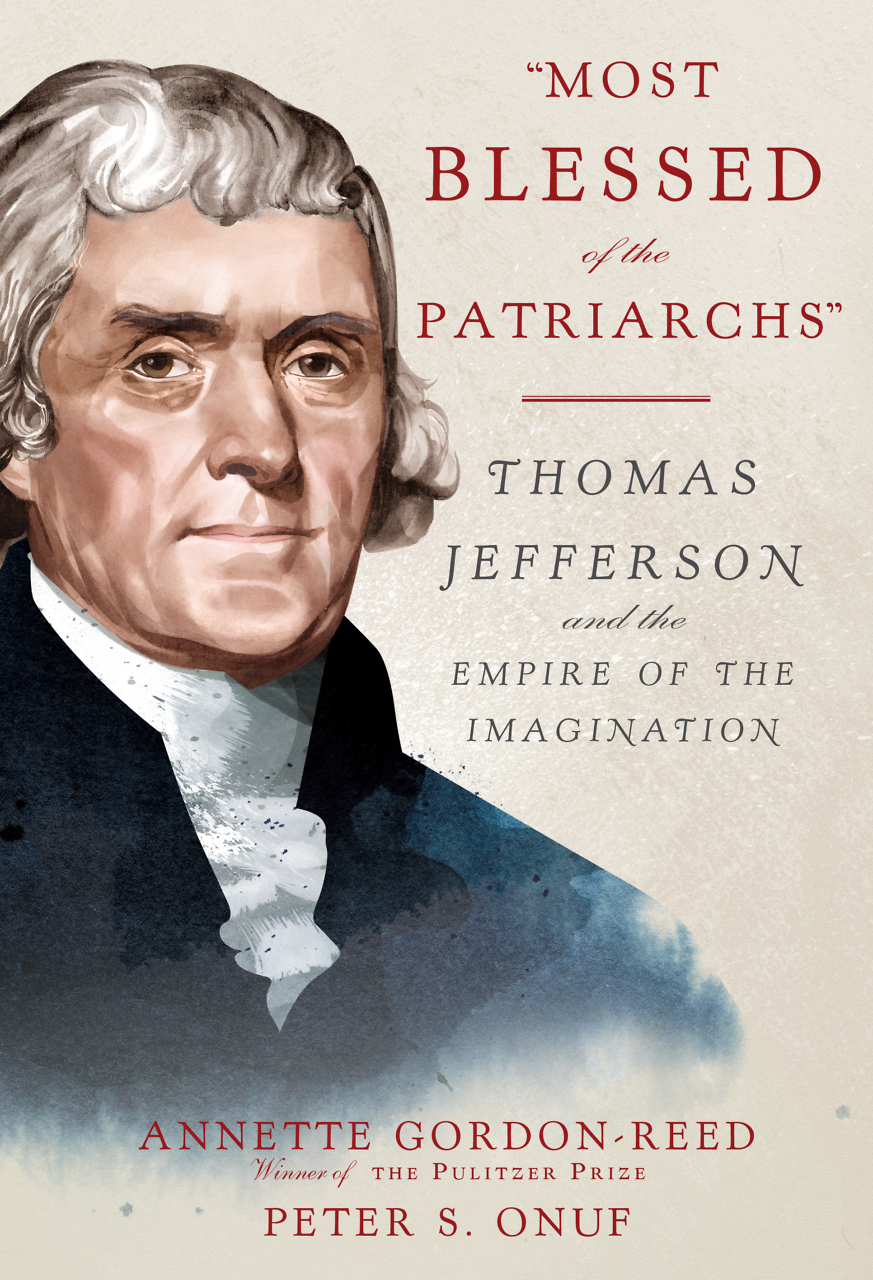

A woman considers her troubled childhood in Elizabeth Strout’s My Name is Lucy Barton

“Such a stupid word, ‘abuse,’ such a conventional and stupid word,” says a character in Elizabeth Strout’s My Name is Lucy Barton. It could be the author herself talking since Strout seems determined in this book to overturn easy assumptions about troubled families and the suffering they create. She takes readers into the mind and heart of a woman who has survived poverty and—yes—abuse, revealing a spirit that is both beautiful and deeply wounded. This intense, first-person novel has little in common with Strout’s Pulitzer Prize-winning story collection, Olive Kitteridge, but that book’s legion of fans will find in Lucy Barton a character as unique and fascinating as the formidable Olive.

Lucy speaks to us as a woman well into the second half of her life, recalling a time when, as a young wife and mother, she was hospitalized for nine weeks with mysterious complications from an appendectomy. Her own mother comes from the Barton family home in the Midwest to sit with her for a few days in her New York hospital room. This is a surprise to Lucy, even something of a shock, since she has been estranged from her birth family in a passive, undeclared way for years. Nevertheless, she feels, at least initially, an unalloyed happiness about the reunion: “Her being there, using my pet name, which I had not heard in ages, made me feel warm and liquid-filled, as though all my tension had been a solid thing and now was not.” Mother and daughter renew their bond by making up nicknames for the nurses—“Cookie,” “Toothache,” “Serious Child”—and sharing gossipy stories of the Bartons’ hometown, but it’s soon clear that something is deeply wrong between them.

Lucy speaks to us as a woman well into the second half of her life, recalling a time when, as a young wife and mother, she was hospitalized for nine weeks with mysterious complications from an appendectomy. Her own mother comes from the Barton family home in the Midwest to sit with her for a few days in her New York hospital room. This is a surprise to Lucy, even something of a shock, since she has been estranged from her birth family in a passive, undeclared way for years. Nevertheless, she feels, at least initially, an unalloyed happiness about the reunion: “Her being there, using my pet name, which I had not heard in ages, made me feel warm and liquid-filled, as though all my tension had been a solid thing and now was not.” Mother and daughter renew their bond by making up nicknames for the nurses—“Cookie,” “Toothache,” “Serious Child”—and sharing gossipy stories of the Bartons’ hometown, but it’s soon clear that something is deeply wrong between them.

We learn early on that the Barton family was desperately poor—so poor, in fact, that Lucy’s early years were spent living in a garage, and she and her siblings were shunned by other children. But as the hospital encounter progresses, much more disturbing truths about Lucy’s childhood are slowly revealed, and we come to understand why she seems to have such a fragile sense of self and why she is so hungry for love and attention that even a doctor’s purely professional kindness wins a permanent place in her heart. “I have always remembered this man,” she tells us, “and for years I gave money to that hospital in his name.”

Lucy’s time in the sickbed takes place in the 1980s, when the AIDS epidemic is at its height in New York. The disease is a powerful presence both inside and outside the hospital. Victims “walked the street, bony and gaunt,” she tells us, and although she is disturbed and moved to sympathy by the suffering she sees, she also feels a strange resentment. She tells a friend, “I know it’s terrible of me, but I’m almost jealous of them. Because they have each other, they’re tied together in a real community.” The sick and dying men are a continual reminder of her loneliness—a loneliness rooted in her troubled childhood, which she seems helpless to shake, despite the outwardly successful adult life she has created: “Loneliness was the first flavor had I tasted in my life, and it was always there, hidden inside the crevices of my mouth, reminding me.”

Lucy’s time in the sickbed takes place in the 1980s, when the AIDS epidemic is at its height in New York. The disease is a powerful presence both inside and outside the hospital. Victims “walked the street, bony and gaunt,” she tells us, and although she is disturbed and moved to sympathy by the suffering she sees, she also feels a strange resentment. She tells a friend, “I know it’s terrible of me, but I’m almost jealous of them. Because they have each other, they’re tied together in a real community.” The sick and dying men are a continual reminder of her loneliness—a loneliness rooted in her troubled childhood, which she seems helpless to shake, despite the outwardly successful adult life she has created: “Loneliness was the first flavor had I tasted in my life, and it was always there, hidden inside the crevices of my mouth, reminding me.”

Though she suffered considerably in her parents’ home, Lucy is remarkably free of anger. There’s a kind of resignation in her, a core passivity that seems damaged, unhealthy, and yet she retains a child’s pure desire for love, and she has a fierce mother love for her own children. It’s tempting to describe Lucy as an innocent, but of course she isn’t. Her innocence was taken from her early on. She is, however, sincere—relentlessly so. It’s almost as if Strout deliberately set out to write a character incapable of irony, snark, or bitterness. In a contemporary cultural landscape where these very qualities are abundant and celebrated, Lucy’s heartfelt voice seems almost otherworldly.

But in spite of the strangeness in Lucy’s character—or perhaps because of it—she is deeply sympathetic. It’s impossible not to root for her, not to want her to find some way of obtaining and accepting the love she craves. And ultimately, it’s impossible not to admire her for the generosity of spirit she shows toward the suffering of others, her parents included. Lucy knows that her hurt is not unique. “But I think I know so well,” she says, “the pain we children clutch to our chests, how it lasts our whole lifetime, with longings so large you can’t even weep.”

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.