Magic Surrealism

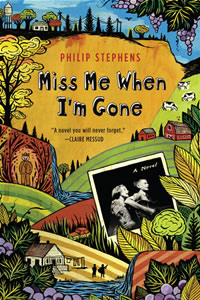

In his stunning first novel, poet Philip Stephens journeys deep into the Missouri Ozarks

During the late Cambrian, shallow seas covered much of the land between the Rockies and Appalachia, their beds thickening with the muck of life. Later, as South America crashed into North America, the land rose. The Ozark Plateau drifted skyward, a great round cake of limestone and chert amid the American plain. Left out in the sun and rain, the cake cracked and fissured. Thrust yourself into its tangled hollows, and you may as well be at the bottom of that Cambrian sea. The life there is odd and unfathomable, the snatches of sound otherworldly, your exact location unknowable. The vegetation is a tangle of oozing fronds that blot out the sun, let alone any hint of encroaching civilization. Such is the mythic Ozark town of Apogee, Missouri, the setting of Philip Stephens’s rich debut novel. Miss Me When I’m Gone represents another kind of collision, where the magic realism of a Garcia Marquez or a Vargas Llosa operates in a setting that evokes Twain, Faulkner, and O’Connor.

The plot is simple enough. Apogee native Cyrus Harper is a folk singer in San Francisco, scraping by on a repertoire heavily influenced by American roots music, at the edges of a second album contract and alcoholism. His older brother calls him home to visit their dying, psychotic mother, Ruth. Cyrus has spent much of his adult life wandering in search of his sister, once the other half of his duo, who vanished mysteriously in her late teens or early twenties. (Ages and dates in the book remain vague and unstated, although fleeting cultural references suggest the story is set in the early 1990s). “He had come west to look for Saro,” Stephens writes of Cyrus. “She had completed his voice—a clear harmony to his reedy melody—and often he thought that if he could just find her, she might lead him back to a place where songs would come to him again.”

As Cyrus travels homeward, another, more sinister, wanderer is also bound for Apogee on a quest. Her name is Margaret Bowman, but she goes “by many names, or no name at all.” Her face is marked by a massive scar which she never explains the same way twice. She wears old floral-print dresses belted by a braided carnival whip and seldom sleeps indoors. “A steady rain had soaked her through,” Stephens writes of her approach to Apogee, “but she just kept moving into the darkness along a new strip of four-lane at the edge of the Ozark Plateau.” Ostensibly searching for a lost daughter, Margaret moves steadily into that Ozark darkness, both figuratively and literally, finding shelter in caves and bridge abutments, until she becomes a villain that is both underworld deity and wholly human.

As Cyrus travels homeward, another, more sinister, wanderer is also bound for Apogee on a quest. Her name is Margaret Bowman, but she goes “by many names, or no name at all.” Her face is marked by a massive scar which she never explains the same way twice. She wears old floral-print dresses belted by a braided carnival whip and seldom sleeps indoors. “A steady rain had soaked her through,” Stephens writes of her approach to Apogee, “but she just kept moving into the darkness along a new strip of four-lane at the edge of the Ozark Plateau.” Ostensibly searching for a lost daughter, Margaret moves steadily into that Ozark darkness, both figuratively and literally, finding shelter in caves and bridge abutments, until she becomes a villain that is both underworld deity and wholly human.

Between these quests by the book’s light and dark protagonists move an unforgettable pantheon of imps, bluesmen, ghosts, holy rollers, aging hippies, good old boys, meth heads, and real estate developers, not to mention Charon, who appears to have retired from the Greek ferry business in order to run a trotline. There are also a few less surreal characters—Cyrus’s developer brother, an old girlfriend turned stripper, and a bubba sheriff—who help move the story along. But while the surface of this story may look familiar, from within it becomes a maze of fissures and swamps. The reader is drawn deeper into the book’s landscape to a point where the very idea of plot no longer seems to matter so much.

What matters instead is song. Ultimately, Miss Me When I’m Gone is about the sources and magical power of song, both music in general and pure American music in particular. Take the oldest 78 from a Nashville estate sale and the oddest recording from any music-edition CD of The Oxford American, and chances are that both are mentioned somewhere in this book, followed by a short discourse on the obscure nineteenth-century tune the song was taken from. (On the other hand, the discourse may be lost amid the shoplifting, sex, or murder taking place on the same page.) Cyrus in his ruminations will run through lists of old titles that become a sort of recurring poetry—“Kicking the Bedpost,” “Rock That Cradle Lucy,” “Fruit Jar Rag”—along with snatches of actual poetry in the form of authentic lyrics, both bawdy and pure.

What matters instead is song. Ultimately, Miss Me When I’m Gone is about the sources and magical power of song, both music in general and pure American music in particular. Take the oldest 78 from a Nashville estate sale and the oddest recording from any music-edition CD of The Oxford American, and chances are that both are mentioned somewhere in this book, followed by a short discourse on the obscure nineteenth-century tune the song was taken from. (On the other hand, the discourse may be lost amid the shoplifting, sex, or murder taking place on the same page.) Cyrus in his ruminations will run through lists of old titles that become a sort of recurring poetry—“Kicking the Bedpost,” “Rock That Cradle Lucy,” “Fruit Jar Rag”—along with snatches of actual poetry in the form of authentic lyrics, both bawdy and pure.

The characters who set the various acts, from first page to last, are a ghostly gang of musicians called “hog-eyed men.” In the novel’s opening pages, they are easy to dismiss as pig-faced visions of Cyrus’s psychotic mother, but they become somewhat more real with each manifestation, their ties to music more profound. “Take us, Cyrus,” one says in a late chapter. “We are wholly American, which means we are not wholly anything.”

In Salmon Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories, the title character asks his father, a master storyteller, where stories come from. “‘From the great story sea,’ he’d reply, ‘I drink the warm Story Waters and then I feel full of steam.’” In Miss Me When I’m Gone, Philip Stephens may have found the source of those Story Waters—in a river of song flowing beneath the Ozarks.

Philip Stephens will read from Miss Me When I’m Gone at Borders Books in Nashville on February 5 at 2 p.m.