Make a Mess of Things

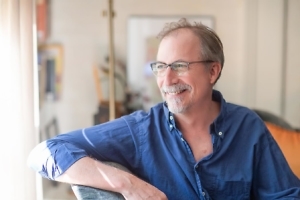

Daniel Wallace returns with a comic romp through a series of Extraordinary Adventures

There’s a long tradition in Southern literature of tales revolving around the travails of a certain type of character we might typecast as the Endearing Eccentric—a peculiar but lovable goof situated in a realistic but offbeat environment inhabited by outrageous characters who draw the protagonist into madcap hijinks, provoking both mirth and rue. Think John Kennedy Toole’s Ignatius Reilly and Winston Groom’s Forrest Gump. Add to this tribe Daniel Wallace’s Edsel Bronfman, a hopelessly naïve but earnest shipping clerk with a bad case of arrested development; a surly, sexually adventurous mother in the early stages of dementia; and a meth-dealing neighbor named Thomas Edison.

The premise of Extraordinary Adventures is simple: one day Edsel receives a phone call notifying him that he’s won a free weekend stay in a luxury beachfront condo in Destin, Florida. He’s determined to take advantage of this offer, less out of any particular interest in Gulf Coast vacationing than because the trip represents a change in his fortunes: “He had won something, something free, something he had accomplished just by being alive.” But there’s a catch, and it’s not merely the contractual obligation to sit through an hour-long sales pitch from a real-estate agent: “The offer is valid for you and a companion,” the operator informs Edsel. “You have to have a companion.” Once this condition sinks in, Edsel resolves to use the time he has before the offer expires—seventy-nine days—to meet a woman and fall in love—or at least to get close enough to enjoy spending the weekend together in Destin.

If this seems a bit silly, well, that’s the point. Extraordinary Adventures fits solidly into the picaresque genre, made famous in American literature by Mark Twain in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: a lovable but guileless (or obtuse) protagonist travels through a series of encounters, enabling the author to satirize the absurdities of his age while carrying his hero out of innocence and into experience, or at least a modicum of understanding.

The chief target of Wallace’s satire seems to be the sort of alienation enabled by a life compartmentalized into finite categories, a life of tame risk-avoidance that make it easy for people to get in the habit of being alone. “His life was simple: he had his job, his apartment, and his mother,” Wallace writes. “His world was triangulated like this, from point A to point B to point C. His life could be summarized by the first three letters in the alphabet.” Edsel Bronfman is a sort of exaggerated embodiment of a life in which there’s always an excuse to avoid taking chances. As readers of Big Fish are well aware, a preference for safety at the expense of joy and pain is anathema to Daniel Wallace. As Edsel’s wacky, chain-smoking, curse-spewing mother says, “Just go out there and for once in your life fuck things up royally.”

Readers accustomed to Wallace’s penchant for zany characters and wacky, larger-than-life situations will not be disappointed. Nevertheless, most of Edsel’s “adventures” take place not on the shores of the Gulf Coast but in the drab environs of Birmingham. In the category of potential love, there’s Coco, a wisecracking Asian hustler in a child’s cowboy hat; Serena, a tough but captivating police officer investigating the wholesale robbery of Edsel’s home; and Sheila, a temp in Edsel’s office who informs Edsel that her dream in life is to write catalogue copy for IKEA. Deciding he’d better get in shape for the beach, Edsel joins the Y, where he labors to overcome the awkwardness of the locker room (“for the first time in his life he found himself in the company of penises other than his own”) and meets Dennis Crouton (“like the crunch bread in salad”), a dissolute art photographer who invites Edsel to a gallery showing and gets him drunk enough to make a hilariously inappropriate proposal to a pair of women he’s just met.

Readers accustomed to Wallace’s penchant for zany characters and wacky, larger-than-life situations will not be disappointed. Nevertheless, most of Edsel’s “adventures” take place not on the shores of the Gulf Coast but in the drab environs of Birmingham. In the category of potential love, there’s Coco, a wisecracking Asian hustler in a child’s cowboy hat; Serena, a tough but captivating police officer investigating the wholesale robbery of Edsel’s home; and Sheila, a temp in Edsel’s office who informs Edsel that her dream in life is to write catalogue copy for IKEA. Deciding he’d better get in shape for the beach, Edsel joins the Y, where he labors to overcome the awkwardness of the locker room (“for the first time in his life he found himself in the company of penises other than his own”) and meets Dennis Crouton (“like the crunch bread in salad”), a dissolute art photographer who invites Edsel to a gallery showing and gets him drunk enough to make a hilariously inappropriate proposal to a pair of women he’s just met.

But there’s more at stake in Extraordinary Adventures than a few laughs. Sheila the temp turns out to be the girl Bronfman might be looking for, an equally odd but sincere traveler who may be the one to help Edsel over the wall between his habits and his hopes. Edsel’s past comes into play as well—both his experiences with first love-gone-wrong and his very origins as related by his nut-case of a mother.

But as with much of Wallace’s fiction, the overarching theme here seems to be the celebration of difference and the importance of resisting an impulse to complacency that has become more and more commonplace in American life. “We really don’t get to make the important choices in our lives,” Wallace writes. “Other people do. They make choices for us. From the second we’re born, most of the choices are already made.” Edsel Bronfman’s quest to find a date for his trip to Destin represents a monumental rebellion against this reality—a last-ditch effort to seize the reins of his own life. Wallace seems to argue that the key to finding meaning and purpose is to be willing, at least once in a while, to “make a mess of things.”

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.