Ministering to the Least of These

A family learns about grace from a death row prisoner

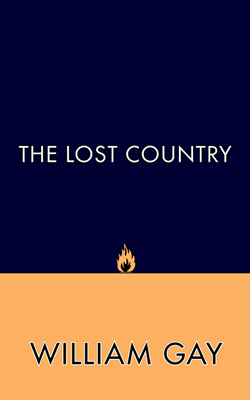

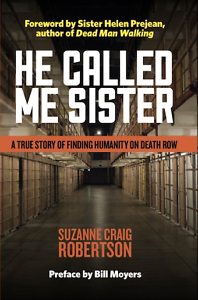

It took Suzanne Craig Robertson about a decade to write He Called Me Sister, which documents the relationship between death row inmate Cecil Johnson and the Robertson family as Johnson’s case winds its way to his execution by lethal injection on December 2, 2009. Johnson was convicted of killing three people, one a 12-year-boy, after robbing a convenience store in Nashville.

The author’s husband, Alan Robertson, was the first to meet Johnson, through an inmate visitation program headed by Reverend Joe Ingle, a Nashville United Church of Christ minister who has been working against the death penalty for nearly 50 years. Over time, Suzanne and their two young daughters also befriended and visited Johnson.

“I did not consider writing about it until several years after his death,” Suzanne Robertson said. Johnson had taken up writing poetry and a memoir in prison and asked for her help in getting published. She got that done by quoting Johnson’s work extensively in He Called Me Sister.

“It has been wrenching to deal with the topic,” Robertson said. “I had the idea, or at least got the gumption to start thinking about it, a couple of years after he died. Then, you know, I had a job and a family, so it’s not like I was working on it full-time. So it came and went and kind of evolved over time.”

Johnson’s childhood is a sordid tale. The beatings, abuse, and poverty he suffered border on the surreal. He Called Me Sister quotes a passage by Johnson about being beaten by his father:

He went beyond the normal and he kept beating me and beating me. My pain had reached the point where I couldn’t bear it any longer, my father lost it and soon I was seeing flashes of light. I wanted to go and die, so I started shouting at my father to go on and KILL ME! KILL ME! KILL ME! I don’t remember when he stopped.

He went beyond the normal and he kept beating me and beating me. My pain had reached the point where I couldn’t bear it any longer, my father lost it and soon I was seeing flashes of light. I wanted to go and die, so I started shouting at my father to go on and KILL ME! KILL ME! KILL ME! I don’t remember when he stopped.

In contrast, the Cecil Johnson the Robertsons got to know was a gentle man who doted on their daughters and accepted his lot in life with remarkable equanimity. Such was his faith that he didn’t believe he would be executed right up until it finally happened.

In the book, Robertson writes about the influence the death row prisoner had on her daughters:

He set an example, like remembering every one of our birthdays — every time — with personal homemade cards, and his ability to laugh and keep a heart full of joy in the face of a hard existence. He shaped their thinking in ways none of us realized, increased their compassion, and caused them to notice injustice in a way no book or lecture ever could have.

The Robertsons were advised by Rev. Ingle not to get involved or even ask about the murders that had doomed Johnson. Guilt or innocence is not supposed to be a factor when it comes to visiting inmates.

“We see this from a religious point of view, whether it’s Jewish or Christian or whatever,” Ingle said during an interview with Chapter 16. “You’re there to visit someone who is your brother, whatever his fate may be. This is a human being, created in the image of God just like you. That’s your focus.”

Despite that, He Called Me Sister makes a convincing case for Johnson’s innocence. His guilty verdict relied on questionable witness testimony.

“I didn’t set out to prove him innocent. … I’m not a lawyer and I’m not an investigative journalist. … I’m a believer in the rule of law,” said Robertson, former editor of the Tennessee Bar Journal, published by the Tennessee Bar Association. “I think it’s the best thing that we have. But when you look at [the Johnson case] up close, it does kind of give us pause, like how did that happen? … I wouldn’t say my faith is completely destroyed in the system, but that was hard to see.”

Ingle, who has counseled many death row prisoners, sums it up like this: “It’s the person who has the worst lawyer who gets the death penalty, not the person who commits the worst murder.”

According to Ingle, Robertson’s book details with “great skill” the pain and the rewards of forging relationships with prisoners. “I would just urge everybody to get a copy because it really is a window into a reality that most people don’t want to know about or even examine,” he said.

For Robertson, the experience was transformative. In He Called Me Sister, she writes, “My relationship with Cecil was teaching me a deeper understanding of forgiveness, which was frustrating. I mean, a lot of times I want others to pay, to hurt, to suffer when they hurt me or my people.”

Already a believer when she met Johnson, Robertson found that the friendship changed her. “I went in having faith,” she said. “Watching him be able to [have a strong Christian faith] in the circumstances he was in helped strengthen it.”

Jim Patterson is a Nashville freelance writer whose work appears often on the United Methodist News website. He has been a reporter for The Associated Press in Nashville and senior writer and public affairs officer for Vanderbilt University.