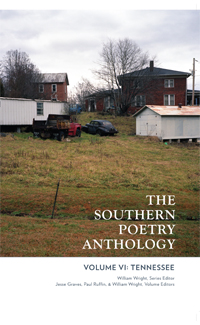

New Anthology Spotlights Tennessee Poets

The Southern Poetry Anthology series turns toward Tennessee

When Southern literature is discussed, poetry tends to be left out of the conversation. And even when poetry gets a word in edgewise, it’s usually the Fugitives who are doing all the talking, especially in a conversation about the poetry of Tennessee. To a degree this is fair: Cleanth Brooks, Robert Penn Warren, and the rest of the gang deeply influenced the course of American poetry—try making sense of a poem without using close-reading techniques, and you’ll see what I mean—but to reflect on Tennessee poetry while failing to discuss the poets who have followed the Fugitives is a grave mistake that occurs far too often. Editors Jesse Graves, Paul Ruffin, and William Wright redress these oversights with their new volume, The Southern Poetry Anthology Vol. VI: Tennessee.

The literary culture of Tennessee is as varied as the landscape of the state, and The Southern Poetry Anthology captures this diversity in the breadth of its selections. From West Tennessee’s Lisa Roney to East Tennessee’s Jeff Daniel Marion, and from nationally celebrated poets like Charles Wright to less familiar talents like Jeff Hardin and Kevin Thomason, the anthology includes a broad array of talent. Transplants to the state including Amy Wright and Blas Falconer are also well-represented.

The literary culture of Tennessee is as varied as the landscape of the state, and The Southern Poetry Anthology captures this diversity in the breadth of its selections. From West Tennessee’s Lisa Roney to East Tennessee’s Jeff Daniel Marion, and from nationally celebrated poets like Charles Wright to less familiar talents like Jeff Hardin and Kevin Thomason, the anthology includes a broad array of talent. Transplants to the state including Amy Wright and Blas Falconer are also well-represented.

The collection highlights what is both local and universal about the work of Tennessee’s poets. Beth Bachmann’s chilling lyricism transcends region, as in her poem “Elegy”:

The lake is filthy

with silver fish sticky with leeches. Lovesick,

I flick a feather into the water. No stones.

Only the one in my pocket, heavy as a tongue.

Although the power of the poem lies in its private emotional weight, it also offers an unsettling description of the state’s landscape. And while Coleman Barks is best known for his translations of mystic Sufi poetry, the selections of his work here are a nice reminder that before he met Rumi his heart belonged to Chattanooga. In “Glad,” for example, he describes a quintessentially American bravado:

She stands up

On the convertible seat holding to the wind-

Shield. WE LOST, WE LOST BIGTIME, TEN TO

NOTHING, WE LOST, WE LOST. Fist pumping

Air. The other team quiet, abashed, chastened.

There’s a welcome array of approaches present in the anthology as well. The formalism of Jim Clark’s “The Land under the Lake,” which deploys iambic pentameter and strong end rhyme, and Thomas Alan Holmes’s use of tercets in “Mandolin” make for an interesting counterpoint to the free-verse lines of Arthur Smith’s “Every Night as I Prayed God Would Kill You” and Brenda Yates’s “Tennessee Jukebox.” Both of these poems revel in the idiosyncrasies of Tennessee’s dialects with descriptions of “the hoopla and shouting” of water on the banks of the Tennessee river and of coffee gone “kindly cold.”

The subjects addressed in this anthology are equally far-ranging, including pastorals (as in Robert Cowser’s “Backtrailing”) that celebrate the beauty of the state’s landscape alongside blistering critiques (like Melissa Range’s “Flat as a Flitter”) of the state’s management of its natural resources. If there’s ever any question about whether poetry is relevant, Range’s poem on mountain-top-removal mining settles it:

The old people say “flitter.” They didn’t live to see

God’s own mountain turned

hazard-orange mid-air pond,

a haze of waste whose brightness rivals heaven.

The collection features many standout selections that would more than hold their own outside a discussion of regional identity. Jane Hicks’s poem “Ryman Auditorium, 1965” is particularly Tennessean, describing the speaker’s experience at the home of the Grand Ole Opry, even as it transcends region by depicting the generational gap between father and child. Early in the poem “…daddy savored / the High Lonesome on thick 78s and slow turning / albums,” but the poem goes on to describe the stereo wars within the speaker’s childhood home: “droning banjos, / chirpy mandolins, crying fiddles drowned out / my Rolling Stones.” In the last third of the poem, during a show at the Ryman,

Flatt and Scruggs

ripped a swift set, caught my ear, then called her out to play

what my heart and bones remembered, Elvis and Paul forgotten,

I gave in to melody and line, riveted to that pew

while Maybelle whipped that guitar into submission.

James Scruton’s poem “Something She Said” also arrives at an emotional state that is simultaneously unique and universal: “From Tennessee to California / Mars is low and red these evenings.” He is literally talking about how the Volunteer State—people and land alike—are “pieces / enough of the universe.” This is what makes poetry matter: its reminder of what people share, its reminder that we are not alone.

Filled with something for all poetic tastes, The Southern Poetry Anthology Vol. VI: Tennessee serves as both an entry point and a refresher for how much the poetry of Tennessee has to offer readers of this state—and of the world at large.