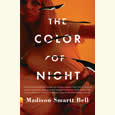

No Accident

Book excerpt: The Current

Rachel Young was in her chair in the living room, writing a letter to one of her two sons, when she heard about the accident. The other son, who still lived with her and who had worked all day, had gone upstairs to bed, and Rachel had the ten o’clock news on with the volume low, and she wasn’t paying much attention to it anyway; she was writing the letter to the son who lived now in New Mexico, just a few words catching him up, such as she wrote every month. In the old trunk under her feet were old photo albums and sheaves of yellowed letters tied up with string and a great hoard of hardback ledgers filled front to back with figures that meant little to her but that told the story of her grandfather’s life, from the neat, fluid hand of his youth to the shaky scratchings of old age. She was using one of the hardback ledgers for a writing surface, and each time she lifted it or set it down she smelled the farm—this farm—and her grandparents’ bodies, and the forever-hot kitchen where her grandfather sat over his figures, slurping coffee as thick and dark as tractor oil.

In the space between the chair and the trunk, beneath the bridge of her legs, slept the old dog, so that she would have to be careful when she stood.

Something on the TV caught her eye and made her look up. It was a young woman’s face, a photograph, a nice one, probably a high school graduation portrait, and Rachel’s first sinking thought was, Oh, no, as it always was when the news showed a pretty young woman’s picture so early in the broadcast. Her next thought was that she knew this girl, had definitely seen her before, and she picked up the remote and raised the volume in time to hear the girl’s name,¬ Audrey Sutter—and she must have cried out then, for the dog raised his face and stared at her with his clouded eyes.

An accident, a slick road, the Lower Black Root River—Rachel’s own heart going cold even before she saw the footage of the frozen river, the jagged hole in the ice, the car already pulled out and taken away.

By the time the program went to commercial break she was out of her chair, the letter forgotten, and she was pacing before the TV, the old floorboards creak¬ing and the old dog watching her. Her heart thudding. Her mind tumbling. What should she do? Who should she call?

Her heart flew immediately to Gordon Burke, a man she’d known so well for so many years—or had known so well until that terrible business ten years ago, that awful business with his own daughter, in this same river—the great sorrow not just of his life but of Rachel’s too. She would like him not to see it on the TV, would like him to be forewarned. But not by her. Then by whom? She thought of Meredith, Gordon’s ex-wife, with whom she’d once been so close, but that friendship had died long ago along with everything else, and as there was no one for her to notify, no one from that old life to talk to, not a thing she could do, she began to clean the kitchen—quietly, her son upstairs sleeping—and when she finished there she cleaned the downstairs bathroom, and when that was done she sat down on the toilet lid and wept as the old dog looked on from his place on the bath mat.

She fixed herself a mug of decaf tea, intending to take it up to bed with her and read her novel until she could sleep, but after fifteen minutes she was still standing at the sink looking out at the cold night, the black oak tree against the snow. Those poor girls! That ice . . . the water running below—the deep, cold under-river that never froze. She stared so long out the window that the snow melted away, and there was grass, and the autumn leaves were tossing in the oak and the view was not of the farm but of the yard and the driveway where she had lived before, when her boys were boys, and she stood now not in the farm kitchen but in that other kitchen, and something had woken her up in the night.

Water.

Water was running in the pipes somewhere. Not the shower, or the toilet, or the kitchen sink: this was the distinctive one-inch-pipe gush you heard when the boys were washing the truck, or the dog, or filling the plastic pool for the dog to splash in. She’d married a plumber and she knew about pipes.

Water was running in the pipes somewhere. Not the shower, or the toilet, or the kitchen sink: this was the distinctive one-inch-pipe gush you heard when the boys were washing the truck, or the dog, or filling the plastic pool for the dog to splash in. She’d married a plumber and she knew about pipes.

Lying awake that night, in that other house, listening. One of her sons would stay out late but when he came home he was like a burglar and if she heard him at all it was because she’d gotten up to use the bathroom, pausing by his door just long enough to hear him clicking at the computer in there, or humming to his headphones, or shushing Katie Goss, his girl.

But she’d heard none of that, that night. Heard nothing at all but the water rushing in the pipes and the wind in the trees. Late October, this was. Almost Halloween. The alarm clock’s red light burning in the dark: 1:59 a.m. Then 2:00 a.m. Rachel pushing back the bedding and standing into her robe, her slippers, and padding down the hall past the boys’ rooms—Danny’s door open, no Danny; Marky’s door shut but him in there, a mound of sleep she could feel like a current in the air—and then down the stairs and into the kitchen, where the water sound was loudest, and there, in the window, was Danny’s truck, lit up by the light she’d left on for him. Two yellow smiley faces staring in at her, plastic hoods for the fog lights or whatever they were he’d mounted on the cab. She saw the truck’s red front fender, the tire, a thin pool of water leaching into the gravel, but no Danny. She leaned closer to the window and just then a face popped up before her so suddenly her hands flew up. Danny, out there, saw the movement and then saw her, and Rachel’s heart surged, as if he were hurt, as if he were washing out some wound she couldn’t see. In the next moment she heard the dog shaking its hide, rattling its tags, and she understood: he would let the dog out in the park, where it would find some other animal’s filth, or carcass, to roll in, and then later would stand under the hose, stupid and happy as Danny hosed it off.

The spigot gave a squeal and the water stopped running and in they came, and the cold air with them. Wyatt shoving past Danny’s legs to dive face-first into her carpet, driving his upper body along with his hind legs, first one side, then the other, grunting in some kind of dog ecstasy.

Wonderful, Rachel said, and Danny said, I’ll dry him when I get back. I gotta go help Jeff. His battery is dead.

Did you get it all off at least? she said, and he flinched, as if she’d shouted.

What? he said.

Rachel gestured at the dog. Did you get it all off?

I got it all off, he said, and turned and was gone again. Nineteen and free to do as he pleased, including, apparently, drinking. There were places they could get into, he and Jeff Goss, and some mornings she smelled the bar on him like he’d slept on its floor. Other mornings she smelled strawberries and knew that Katie Goss, Jeff’s younger sister, had been in the house. Rachel did not approve of such things, of course … but then she’d remember the night she heard them laughing behind his door and she could smell the strawberries and she’d been so angry she rapped on the door and hissed that it was late and he was going to wake up his brother, and the laughing stopped and the bed squeaked and to her horror the door swung open and there he stood, with his smile, fully clothed. Beyond him, on the bed, sat Katie Goss and Marky, smiling at her too, holding their hands of playing cards. Ma, said Danny, come in, we need a fourth. Yeah Momma come in we need a fourth! cried Marky. Plenty of room up here, said Katie Goss. And there they’d sat on the little bed playing cards until one in the morning, when finally she’d gotten Marky to go back to his room, and Danny had driven Katie home to her parents.

He would test her in some way, Danny would, and then he’d fill her heart with love. He’d been taking classes at the college then—engineering! Bridges and dams!—and he could’ve moved out, he had a good job with Gordon Burke, but he was staying home to save money, he’d said, and that was fine. He could call it whatever he wanted; she knew it was for his brother. She knew he’d stayed home for Marky.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Tim Johnston. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved. Tim Johnston is the author of the novels Descent and The Current (which will be released on January 22, 2019), the story collection Irish Girl, and the YA novel Never So Green. He is a former professor of creative writing at the University of Memphis.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Tim Johnston. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved. Tim Johnston is the author of the novels Descent and The Current (which will be released on January 22, 2019), the story collection Irish Girl, and the YA novel Never So Green. He is a former professor of creative writing at the University of Memphis.