No Knack for Volition

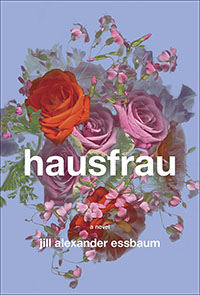

In Hausfrau, Jill Alexander Essbaum invokes Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary to create her heroine’s erotic misadventures

When Anna—the ex-patriate heroine of Jill Alexander Essbaum’s novel, Hausfrau—falls into an extramarital tangle with a fellow foreigner, her assertive pursuit of this lover would seem to fly in the face of her entire nature as a person. Her passivity has long been a defining feature of her identity, “the hub from which the greater part of her psychology radiated.” Through wit and erotic detail, Hausfrau reckons with the consequences of rousing one’s life to action.

Anna has never been one to act on her desires. In her life, “everything came down to a nod, an acquiescence, a Yes, dear. Anna was aware of this. It was a trait she’d never bothered to question or revise.” Her life as an isolated ex-pat does nothing to remedy these passive tendencies. During her nine years in a small town outside Zürich, she’s avoided learning German, making Swiss friends, getting a driver’s license, and confronting her dissatisfying marriage to Bruno, a Swiss banker. Even the births of her three children, whom she assures herself she does love, “just seemed to happen.”

Hausfrau enjoys a playful awareness of its literary antecedents, Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary. Like those heroines, Anna finds more awakening than she bargained for once she makes the decision to pursue her desires. At the novel’s opening, her impotent ennui has reached a breaking point. Bruno has instructed her to address her inadequacies, and Anna agrees to enroll in a German-language class filled with other foreigners, including an appealing Scotsman named Archie. Despite having “no knack for volition,” Anna surprises herself by immediately diving into a passionate affair.

Essbaum presents her protagonist in a slightly wry, brisk tone, which, in addition to providing tonal resonance with those classic European novels, also feels necessary to make Anna more palatable as a character. That sliver of ironic distance allows the novel both to stave off a reader’s judgment and avoid the treacly depths of her angst.

Interspersed throughout the novel are exchanges between Anna and Doktor Messerli, her psychiatrist. This aspect of Anna’s life adds a modern wrinkle to the line of Kareninas and Bovarys, but it’s one that makes good sense. What exploration of a post-Freudian woman in a Germanic culture would be complete without an opining analyst in tow? Anna has a habit of lying to Doktor Messerli and (at least silently) questioning her therapist’s insights and theories. Because we are privy to Anna’s inner life, the dynamic between doctor and patient retains its nuance, making the narrative device fresh.

Interspersed throughout the novel are exchanges between Anna and Doktor Messerli, her psychiatrist. This aspect of Anna’s life adds a modern wrinkle to the line of Kareninas and Bovarys, but it’s one that makes good sense. What exploration of a post-Freudian woman in a Germanic culture would be complete without an opining analyst in tow? Anna has a habit of lying to Doktor Messerli and (at least silently) questioning her therapist’s insights and theories. Because we are privy to Anna’s inner life, the dynamic between doctor and patient retains its nuance, making the narrative device fresh.

The erotic content of Anna’s life provides another tough literary needle for Essbaum to thread. Hausfrau marks Essbaum’s debut as a novelist, and her background as a noted writer of erotic poetry stands her in good stead here. Anna’s sexual encounters and fantasies manage to be genuinely erotic without the risk of inadvertent comedy inherent in so many narrative representations of frank sexuality. As Anna awakens to the possibilities of taking action, her sexuality keeps on surprising her.

Like the affairs of classic heroines before her, Anna’s trysts begin to carry insinuations of approaching consequence, as well as hints of secrets from the past. Within the passion lies the central question for Anna’s life: what will these forbidden actions yield? Essbaum has created a heroine who allows us to enjoy her misadventures but also to step back and watch as her secrets threaten the passive surface of her life. Hausfrau makes it tough for us to decide what we want for Anna but easy to keep turning the pages.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction is forthcoming from The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Late Night Library, Yemassee, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.