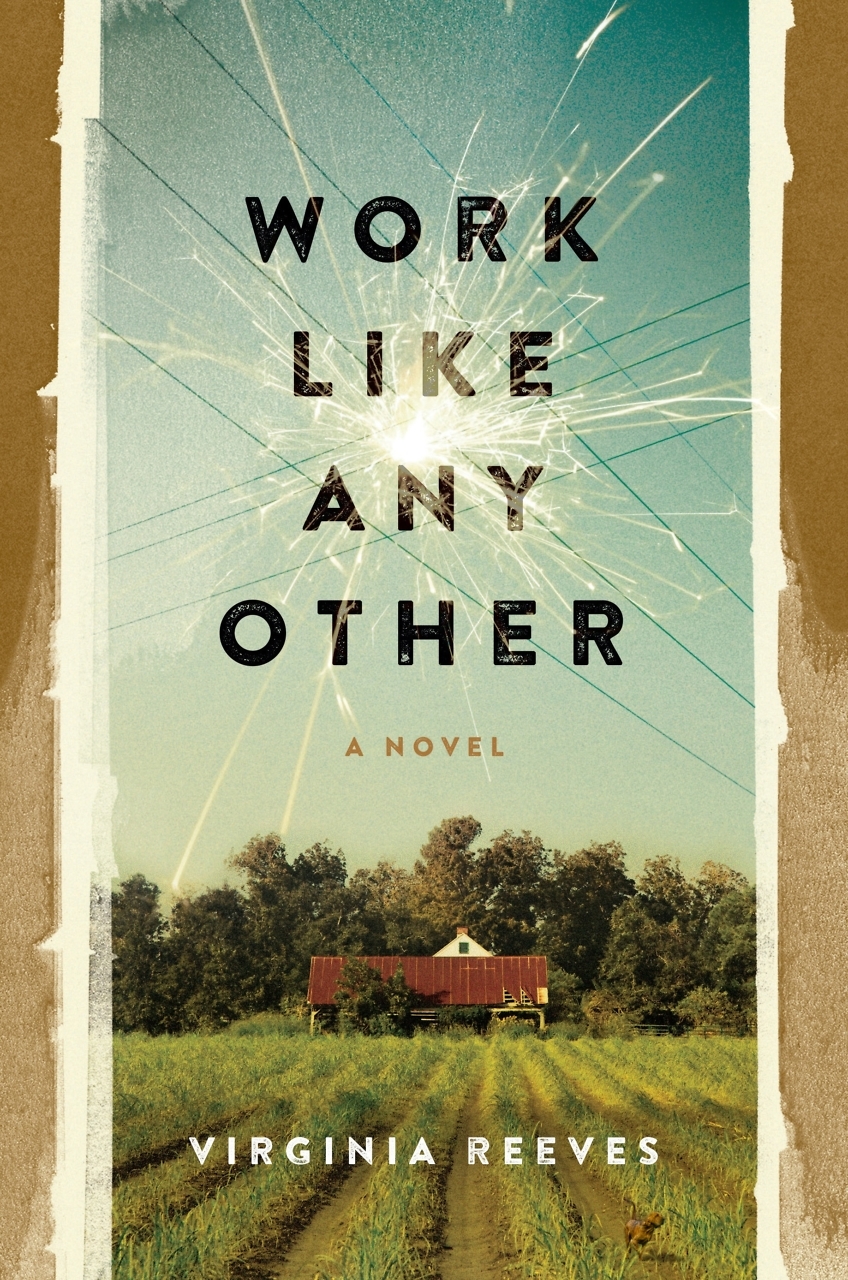

Noir Way Out

Willy Vlautin combines suspense and social commentary in The Night Always Comes

Willy Vlautin is concerned with America’s working poor. Whether you encounter his writing via his alt-country band Richmond Fontaine, his award-winning fiction, or the film The Motel Life (based on one of his novels), Vlautin delves into the dark underbelly of American cities and sheds light on individuals caught up in the systemic web of poverty.

Vlautin’s latest novel The Night Always Comes is no different in theme, but its dynamic heroine and neo-noir edge render it a standout in the realm of literary crime fiction. Set over the course of two fast-paced days and two sleepless nights, the reader follows 30-year-old Lynette as she navigates her two jobs while attending community college, caring for her developmentally disabled brother, Kenny, and coming up with money to buy the ramshackle rental home she lives in with her brother and their jaded single mother.

When it comes time to put the down payment on their home in an increasingly gentrified Portland, Lynette and her mother clash over whether it’s worth it. Her mother becomes exasperated: “I’ve worked at that Fred Meyer Jewelers for so long and all I have to show for it is being able to get a twohundred-thousand-dollar loan on an overpriced, falling-down piece-of-shit house?” She impulsively purchases a new car instead, and Lynette’s hardscrabble efforts to cover the deficit and secure the house begin.

Vlautin’s stark, direct prose is the ideal form to mirror the urgency of the book’s grim content. Nail-biting suspense permeates the novel’s 48 hours as Lynette embarks on a mission to collect what she’s owed from a plethora of seedy characters, and ultimately from versions of herself. As she drives around town running these dark errands, she’s plagued with reminders of how Portland isn’t the same city she grew up in, that it’s no longer a place in which she belongs. At one point, she confesses this sense of displacement to a friend: “I’m realizing that the whole city is starting to haunt me. And all the new places, all the big new buildings, just remind me that I’m nothing, that I’m nobody.”

Throughout the novel, the reader learns that Lynette’s crushing self-doubt is the result of exploitation, not only via systems of power but also in more personal ways. A series of abusive sexual relationships inflict trauma that reveals itself in bursts of unpredictable behavior, further isolating her from those she loves. Her mental health suffers as she scrambles to punch the clock and care for everyone and everything but herself. The despair is palpable for the reader as we witness Lynette buckle under the collective weight of so many factors — destitution, displacement, and abuse — and become tangled in a web of greed, sometimes taking more than she’s owed.

Throughout the novel, the reader learns that Lynette’s crushing self-doubt is the result of exploitation, not only via systems of power but also in more personal ways. A series of abusive sexual relationships inflict trauma that reveals itself in bursts of unpredictable behavior, further isolating her from those she loves. Her mental health suffers as she scrambles to punch the clock and care for everyone and everything but herself. The despair is palpable for the reader as we witness Lynette buckle under the collective weight of so many factors — destitution, displacement, and abuse — and become tangled in a web of greed, sometimes taking more than she’s owed.

The tethers of Lynette’s quest are her relationships with her brother, whose outlook inspires her, and her mother, whom she genuinely cares for but is afraid to become. Her mother’s embittered attitude inflames the fragility of Lynette’s emotional state, and their conversations consistently turn hostile: “Tears welled in Lynette’s eyes and she didn’t say anything. She wanted to argue, she wanted to stand up to their mother, but it all just flooded over her like wet concrete. The guilt and shame of what she’d done and what had been done to her. It took the wind from her, and so she just sat there.”

Lynette’s reactions to freeze or to fight when things become overwhelming are not sustainable, and she must face a crossroads at the conclusion of the novel: facing herself and her needs or spiraling out in the same old cycle of resentments.

No matter how hard Lynette works or how many bootstraps she pulls up, the cyclical nature of poverty is fierce. The Night Always Comes conveys the looming inevitability of gentrification in American communities with a deeply human story about an individual’s relationship to her rapidly changing world. The word “gentrification” is never uttered, however, proving that Vlautin is invested in creating an immediate, immersive world and a narrative that is as approachable as it is devastating. Despite their heaviness, these 200 pages turn quickly, rendering this work a gritty yet graceful must-read.

Lauren Turner is a multidisciplinary artist in Nashville. Her writing has appeared in The East Nashvillian, Women’s Review of Books, and Image Journal’s “Good Letters” blog. She also serves as a blog editor for Nashville’s community radio station, WXNA FM, where she hosts her program The Crack in Everything.