Not So Different After All

Jeannette Walls talks with Chapter 16 about writing a bestselling memoir and a bestselling novel

Dorothy Allison, grand dame of Southern storytelling, once said that while everyone may have a story to tell, “most people shouldn’t try to write it.” This advice might sound harsh, but Allison is on to something: compelling it-happened-to-me stories abound, but far more rare is the skill and sensibility to turn that personal history into an equally compelling written narrative. Jeannette Walls possesses such gifts, not to mention the courage required to reveal—after years of concealment as she climbed up the ranks of New York journalism, becoming a columnist for MSNBC—the disturbing, astonishing truth about her hardscrabble childhood. The book that resulted, The Glass Castle, earned Walls millions of fans and rave reviews; it is now considered by many to be a standard-bearer of the genre and has become a staple of many high-school and college English reading lists.

Readers hung on every word of Walls’ depiction of her neglectful, eccentric parents: Rex, a seductive, intelligent alcoholic prone to “doing the skedaddle” when the going got tough; and Rose Mary, an irresponsible, frustrated artist who squirreled away candy for herself while her children went hungry and later took up the life of a squatter in New York City. The book is riveting not only for the sometimes horrifying details of the family’s experience, but also for the abiding compassion in its narration. “Walls has a telling memory for detail and an appealing, unadorned style,” wrote Francine Prose in The New York Times Book Review. “And there’s something admirable about her refusal to indulge in amateur psychoanalysis, to descend to the jargon of dysfunction or theorize (beyond certain tantalizing clues that occurred to her during their stay with her West Virginia grandmother) about the sources of her parents’ behavior. But what’s best is the deceptive ease with which she makes us see just how she and her siblings were convinced that their turbulent life was a glorious adventure.”

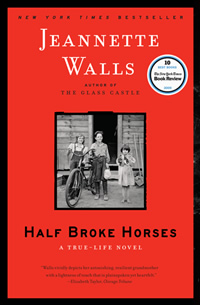

The Glass Castle would be a tough act for any writer to follow. But Walls had an equally captivating tale nestled in her family tree: that of her mother’s mother, Lily Casey Smith, an early-twentieth-century rancher and rural schoolteacher. In Half Broke Horses, Walls recounts Lily’s remarkable life on the range, piecing it together largely from interviews she conducted with her mother. Lily breaks horses as a young girl, rides 500 miles solo on a mustang named Patches, and later takes flying lessons—to list just a few of her exploits. She’s a character cut from the same cloth as figures like Annie Oakley, Davy Crockett, and Daniel Boone—and the book makes it clear that Walls’s indomitable spirit and resourcefulness are, at least in part, inherited.

The Glass Castle would be a tough act for any writer to follow. But Walls had an equally captivating tale nestled in her family tree: that of her mother’s mother, Lily Casey Smith, an early-twentieth-century rancher and rural schoolteacher. In Half Broke Horses, Walls recounts Lily’s remarkable life on the range, piecing it together largely from interviews she conducted with her mother. Lily breaks horses as a young girl, rides 500 miles solo on a mustang named Patches, and later takes flying lessons—to list just a few of her exploits. She’s a character cut from the same cloth as figures like Annie Oakley, Davy Crockett, and Daniel Boone—and the book makes it clear that Walls’s indomitable spirit and resourcefulness are, at least in part, inherited.

In the end, Half Broke Horses provides some clues as to how, as Liesl Schillinger put it in the New York Times Book Review, an “adrenaline-charged background” may have engendered a “lifelong taste for vicissitude” in Rose Mary Walls. But Lily’s story is still very much her own. Writes Nicole Brodeur in The Seattle Times: “Walls doesn’t just describe her grandmother’s life, she channels her in a plain, no-bull tone as stark as the high desert where she was raised….Those who dabble in genealogy, or sit before older relatives, a recorder in hand, will be inspired by what Walls has done with her grandmother’s story. And they will hear Lily Casey Smith’s voice in their heads, telling them to just get to it.”

On the eve of a visit to Davis-Kidd Booksellers in both Memphis and Nashville, Walls took the time to talk to Chapter 16 about the experience of family storytelling and what she’s learned about herself in the process.

Chapter 16: You’ve described writing The Glass Castle as cathartic on several different levels. Was writing Half-Broke Horses a cathartic experience, too, if perhaps in a different way?

Walls: Absolutely. Interviewing a family member, finding out about your ancestors and your own history, is really interesting and for me was extremely illuminating. Patterns emerge. Seemingly inexplicable behavior suddenly makes sense. I’m on a campaign to get people to tell their stories; if they’re lucky enough to have parents or grandparents around, to interview them, and if they’re the patriarch or matriarch of their family, to tell, write, or record their stories. Just do it. Get your stories down on paper or a computer or on the back of a napkin, but record them.

Chapter 16: You seem to have a healthy dose of Lily in your world view. What similarities between Lily and yourself did you discover as you were writing, and were you surprised by them?

Walls: I’m a big believer in pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, making the most of a situation and looking on the bright side of things. That can be an asset, but I’ve come to understand that it can also lead to intolerance, and I need to learn to cut people a little slack. Both Lily and I share a tendency to try to make the world better—sometimes excessively so. One of the things I’m trying to learn from my mother is that often things and people are who or what they are, and you’ll be a lot happier if you accept that.

Walls: I’m a big believer in pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, making the most of a situation and looking on the bright side of things. That can be an asset, but I’ve come to understand that it can also lead to intolerance, and I need to learn to cut people a little slack. Both Lily and I share a tendency to try to make the world better—sometimes excessively so. One of the things I’m trying to learn from my mother is that often things and people are who or what they are, and you’ll be a lot happier if you accept that.

Chapter 16: You spent hundreds of hours interviewing your mother for this book. Give us a glimpse of those hours: What was the process like? Do you have any suggestions for aspiring writers who want to tell their families’ stories but are anxious about the process of grilling a family member?

Walls: Mom was really quite wonderful and forthcoming. Not once did she tell me not to use something because it was too revealing or too embarrassing or whatever. Her recall for Arizona history and geological details was stunning to me. Several times when I was interviewing her, I’d think, “She couldn’t possible know all this stuff”; then I’d Google it, and she was usually dead-on.

I got lucky with Mom’s candor. A lot of people believe that they want to talk about the past, but they’re very conflicted about opening up, they feel guilt or shame and just might not be ready to face the past. If they are at least willing to try, though, I think they would find it hugely revelatory.

Chapter 16: On the one hand, Lily Casey Smith was always forward-looking, always progressive; she eschewed her father’s preference for the past over the future. But there seems to be some conservatism in her character, too—which is to say you’ve captured her delightfully true-to-life, consistently inconsistent nature. Would you agree with that assessment?

Walls: I think that’s an incredibly perceptive observation. Lily liked to think of herself as a modern, civilized woman, but she always had one foot in the frontier and was a lot more half-broke than she’d ever admit. That’s not an entirely bad thing.

Chapter 16: You’ve now written a work of literary nonfiction and a “true-life novel.” Can you talk about the difference between them from an artistic point of view?

Walls: For me, they were a lot closer than I would have thought. My goal with Half Broke Horses was not to embellish or tart up the truth, but to get as close to Lily’s story as possible. Many times, when I was interviewing Mom, she’d say something like, “I’ve heard conflicting stories on this…” or “You know how I am with numbers, Jeannette, but I believe this happened in 1911….” So I had the choice of writing the book as “nonfiction” [and] then qualifying the heck out of it with those phrases historians use, such as “evidence suggests”—which I think take readers out of the story. Since I wanted to tell it in Lily’s voice, I just went with what Mom told me and filled in gaps. I wanted the story to be as real as possible. It’s not that the truth is stranger than fiction; it’s more nuanced, more complex. I could have never made up Lily Casey Smith. My goal was simply, as much as possible, to capture her spirit.

Jeannette Walls appears at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on September 8 at 6 p.m. and at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on September 9 at 7 p.m.