Not What You See, But What You Perceive

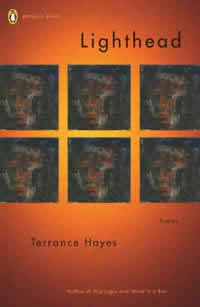

Poet Terrance Hayes adopts lightheadedness as an aesthetic stance

With his first collection, Muscular Music, Terrance Hayes won a prestigious Kate Tufts Discovery Award for a first book of poems—and set the stage for what he would become today: one of the country’s most popular and innovative poets. Hayes is the recipient of many honors, including a Whiting Writers Award and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. Originally from Columbia, South Carolina, he attended Coker College on an athletic scholarship but he decided during his senior year to write poetry for the rest of his life. Currently, he is a professor of creative writing at Carnegie Mellon University and lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with his wife, poet Yona Harvey, and their two children, Ua and Aaron.

Hayes’s fourth collection of poems, Lighthead, won the National Book Award in poetry this year. Intense in both its imaginative pairings and rhythms, the book takes readers into another realm. Personal meditations are paired with diverse cultural and historical references, such as Malcom X, Wallace Stevens, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and more. Reviewing Lighthead, Granta editor John Freeman wrote that “poetry has two kinds of music. There is the sound it makes when read aloud, and then it has an inner composition, too—the strange, occult rhythm that verses make when your mind, not your lips, mouths the words. Terrance Hayes is one of the rare poets who can braid these two sounds into a kind of harmony.”

In this collection, Hayes adopts a kind of lightheadedness as an aesthetic stance: in each poem, the speaker lassos and releases gravity, time, and experience, reminding readers that “when you spend your nights / out on a limb, there’s a chance you’ll fall in your sleep.” Hayes recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email prior to his appearances at both the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

Chapter 16: Lighthead is one impressive book. What is also impressive is the long list of styles that critics ascribe to the collection. I’ve read it described as postmodern, free-associative, Freudian, and surrealist, to name a few. It’s the surrealist tag that I’m wondering about the most. The opening poem, “Lighthead’s Guide to the Galaxy,” plays with a phrase by one of surrealism’s great influences, Rimbaud. He talked about his poetry in terms of “the systematic derangement of the senses.” You write: “Not what you see, but what you perceive: / that’s poetry. Not the noise, but its rhythm; an arrangement / of derangements….” Lightheadedness is definitely an aesthetic stance in this book, but I’m not quite seeing the surrealist connection. Maybe it’s how you define it: would you consider yourself a surrealist?

Terrance Hayes: I think there is a gray area between surreal and real. Most of life seems surreal to me, and I suppose I try to be faithful to that sense of things when I write. I’m more drawn to the surrealist label than, say, post-modern or free-associative or Freudian—not because those terms lack meat for me, but because each seems to float into/around surrealism.

Terrance Hayes: I think there is a gray area between surreal and real. Most of life seems surreal to me, and I suppose I try to be faithful to that sense of things when I write. I’m more drawn to the surrealist label than, say, post-modern or free-associative or Freudian—not because those terms lack meat for me, but because each seems to float into/around surrealism.

Chapter 16: How do you view Lighthead in relation to your other three poetry collections that came before it? In other words, how have you seen your style or poetic interests evolve through the years?

Hayes: I hope my style has evolved in the same ways my life has evolved. I try to take it one poem at a time, one day at a time. In my dream my style resists style. I chase discovery, risk—though with each new poem, those seem like impossible, terrifying objectives. Maybe I’m not answering your question. I think writers have their obsessions. I really can’t get away from music. I’ve just tried to change the ways I deal with the subjects over the years.

Chapter 16: Speaking of music, one element that most reviewers cannot help but comment on is your poems’ rhythms and free-rolling, associative leaps of imagination. Let me give readers a little example of what we are talking about from your poem “Anchor Head”:

Because keyless and clueless,

Because trampled in gunpowder

And hoof-printed address,

From Australopithecus or Adam’s

Dim boogaloo to birdsong

And what the bird boogaloos to,

Because I was waiting to break

These legs free, one to each

Shore, to be head-dressed in sweat….

I hate to cut the quote there, but this is a twenty-seven-line poem that never rests until the end. What catches my attention here is how you move through the associations. A lot of poets will do so visually or conceptually, but you do so sonically. For example, in the first line the “K” sounds lead with “cause,” “key” and “clue.” What are some of the guiding principles behind your associations? Or is this something that you don’t consciously think about, something that is guided more by what you read or listen to?

Hayes: That poem and a few others (“Three Measures of Time,” for example) associate via sound. I was playing with the principle of echoing lines.

Hayes: That poem and a few others (“Three Measures of Time,” for example) associate via sound. I was playing with the principle of echoing lines.

Chapter 16: Another dazzling element to this collection is the array of forms: you create them. For example, each of the book’s four sections features a series of poems that are riffs on the pecha kucha (pronounced pe-chak-cha), which the book describes as a Japanese presentation format. Could you talk more about this form? What sort of presentation is this in Japan? How did you get interested in the pecha kucha and its application to poetry?

Hayes: Oh, long story. I bet you can find the backstory in an interview or review somewhere online. I wanted a way to write a long lyric poem and the poem’s twenty associated parts gave me a way to do it. I’ve written one more successful one since the book was published but I usually move past the forms I devise once they’ve satisfied me.

Chapter 16: You are a rock-star in the poetry world. (Surely your spring-fashion spread in T: The New York Times Style Magazine confirmed whatever the National Book Award did not.) What’s a “typical day” like for you now? How do you balance writing with all the other demands on your time?

Hayes: The demands in my day-to-day life are the same: parenting, teaching, writing. Things are a bit more intense when I travel—which is why I only travel once a month. The writing presents the same challenges and joys, though.

On September 21 at 7 p.m., Terrance Hayes will read at the University of Tennessee’s John C. Hodges Library auditorium in Knoxville. He will also host an informal discussion from 3-4 p.m. in 1210-1211 McClung Tower also on Knoxville’s campus. Hayes will also read with Jaimy Gordon at Vanderbilt University’s Sarratt Student Center Cinema in Nashville on September 22 at 7 p.m. All events are free and open to the public.