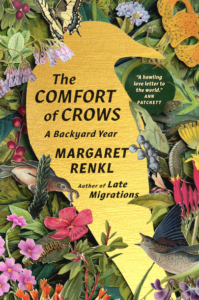

Of Berries and Death

Book Excerpt: The Comfort of Crows

The serviceberries came and went, and I didn’t get so much as a taste — the mockingbirds plucked them from their stems as quickly as the berries could ripen. I’ve heard stories of determined old-timers who would keep close watch on woodland stands of serviceberry trees, sleeping beneath them to gather newly ripened berries at dawn, before the birds could lay claim. But feeding the birds is why I planted my serviceberries in the first place, and I am happy to cede every blue berry to them. I’m not certain I’d prevail in a contest with a mockingbird anyway.

The blackberry harvest is bountiful this year, enough for us and the mockingbirds, too. The thornless canes growing on the fence behind my pollinator beds aren’t wild berries — they belong to a cultivated variety passed along by a friend — but the birds can’t tell the difference, it seems, and I can’t either. Any blackberry ripe in the summer sun, no matter the variety, is the taste of my childhood.

But there’s a primitive connection in me that runs straight from blackberries to rattlesnakes. So many creatures feast on ripe blackberries that it’s hard to imagine a more promising spot for a rattlesnake to set up camp, and every year when my canes are thick with fruit, when they are entwined with passion vines thick with blooms, I must work to remember that no rattlesnakes — shy creatures who would not be at home in this artificial neighborhood — are coiled beneath their tangles. “There are no rattlesnakes here,” I repeat to myself. “I don’t need to look for rattlesnakes.” Though I am a profound respecter of snakes, I confess I am not sorry about the absence of rattlesnakes from this particular spot in the first-ring suburbs.

It’s dumbfounding to me when I think about it now, the way our grandmother would send us — my siblings and cousins and me — out to pick blackberries, promising to make us a cobbler if we filled our pail. “Watch out for rattlesnakes,” Mimi would say, with no more solemnity than if she were warning us to come home in time for supper. And that’s how I know that rattlesnakes were common in that time and in that place, though they are imperiled today — by habitat destruction, by climate change, always by human ignorance. Anybody picking wild blackberries in the Lower Alabama of my childhood was almost certainly sharing that skein of canes with a hidden rattlesnake.

But thinking about Mimi’s admonition, the careless way she handed us a pail and told us to keep an eye out, almost offhandedly, is also how I know that rattlesnakes take care to avoid human beings. My grandmother would not have sent us into danger. As long as we were careful not to step on a waiting snake, we were perfectly safe picking blackberries — as safe as any child can be in the fields or the woods, at least. In those days, no one would have thought to keep a wondering child away from the fields or the woods.

Here in this rattlesnake-barren yard in Tennessee, the pokeberries begin to ripen just as the blackberries are giving out. I sit at my writing table in our family room, the one in front of a row of windows facing a row of pollinator beds, and watch a brown thrasher and a mockingbird try to drive each other away, intent on protecting the pokeberries for themselves. I’m amazed when the thrasher wins the battle.

Here in this rattlesnake-barren yard in Tennessee, the pokeberries begin to ripen just as the blackberries are giving out. I sit at my writing table in our family room, the one in front of a row of windows facing a row of pollinator beds, and watch a brown thrasher and a mockingbird try to drive each other away, intent on protecting the pokeberries for themselves. I’m amazed when the thrasher wins the battle.

No one would camp out beneath a stand of pokeweed to beat the mockingbirds to the berries. Pokeweed is toxic to humans and dogs. The old poke salat of country lore, frequently mispronounced in pop culture representations of poor folk, is not a salad but a mess of cooked greens, and only the newest shoots of spring can be safely cooked. I am not a forager, and I have never tried to make poke salat — habitat is in such steep decline that I prefer to leave wild foods for wild creatures. Also, I don’t trust myself. When a plant is edible only under certain conditions and poisonous under all others, I have no interest in testing my luck.

My husband is so worried that the toddler next door might be tempted to help herself to a pokeberry that he has cut down the branch that hangs over the fence between our driveways, and I am careful to keep Rascal away from the berries that hang on our side. We needn’t worry: The birds won’t leave those berries alone long enough for even one of them to fall to the ground.

[A selection of Billy Renkl’s artwork from The Comfort of Crows can be seen here.]

Excerpted from The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard Year by Margaret Renkl. Reprinted with permission from Spiegel & Grau. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved. Margaret Renkl is the author of Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss and Graceland, At Last: Notes on Hope and Heartache From the American South. She is a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times and the founding editor of Chapter 16. She lives in Nashville.