Off the Grid

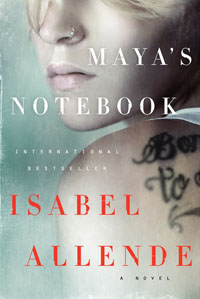

Isabel Allende discusses her new novel, Maya’s Notebook, and explains her affection for vagabonds and the terrors of modern parenting

Isabel Allende has gained a large and devoted international readership by revealing the dark secrets and searing pains that afflict the human heart. Her stories are filled with incidents—journeys, missions, fights, and love affairs—but the real action takes place on the inside, where her characters’ consciences collide with their passions. In Allende’s new novel, Maya’s Notebook, a teenage girl living with her grandparents in Berkeley, California, begins a downward spiral into drug addiction after the death of her loving grandfather. A grandmother herself, Allende clearly sympathizes with Maya’s Nini, who feels helpless against the very real demons that haunt her granddaughter.

When Maya’s drug habit causes her to run afoul of the law, Nini convinces her to leave Berkeley and go to a rehabilitation clinic in Oregon. There she takes tentative steps toward lasting sobriety but eventually feels cramped and runs away. A harrowing series of events—including Maya’s pursuit by violent criminals—leads Nini to send her to stay with an old friend on a remote island, Chiloé, off the coast of her native Chile. Deprived of most modern amenities, Maya fills her journal with the story of how her life took its fateful turns. This premise gives Allende an effective vehicle for exploring the psychological trauma that led to her heroine’s downfall and for detailing the halting process of recovery. As in all of Allende’s work, the spirit world overlaps the material one; helpful ghosts arrive at propitious intervals to steer the living toward the right paths.

When Maya’s drug habit causes her to run afoul of the law, Nini convinces her to leave Berkeley and go to a rehabilitation clinic in Oregon. There she takes tentative steps toward lasting sobriety but eventually feels cramped and runs away. A harrowing series of events—including Maya’s pursuit by violent criminals—leads Nini to send her to stay with an old friend on a remote island, Chiloé, off the coast of her native Chile. Deprived of most modern amenities, Maya fills her journal with the story of how her life took its fateful turns. This premise gives Allende an effective vehicle for exploring the psychological trauma that led to her heroine’s downfall and for detailing the halting process of recovery. As in all of Allende’s work, the spirit world overlaps the material one; helpful ghosts arrive at propitious intervals to steer the living toward the right paths.

In a recent email exchange prior to her event at the Nashville Public Library on May 3, Allende answered questions about Maya’s Notebook and about the perils of obeying the commands of the heart.

Chapter 16: Maya’s story is not simply about healing; it’s also about redemption: she must find ways to make up for the pain she has caused her family—her grandmother, in particular. How is the relationship between those two sides of her story, the psychological and the moral, best understood?

Isabel Allende: When I write fiction I don’t intend to deliver a message, just tell a story. In the rural community of the island, Maya needs to learn that there is natural justice, a law of reciprocity: you have to give as much as you receive. Sometimes she can’t pay a favor to the person who has done it to her, but she is morally obliged to render an equivalent favor to somebody else. Without reciprocity it would be very difficult to survive in the harsh conditions of Chiloé (especially in winter). From being a spoiled brat, Maya learns quickly that if she wants to be accepted by the community she has to be useful.

Chapter 16: In Maya’s Notebook and in other of your novels, you seem to strike a balance between darkness and light, between the designs of evildoers and the fortitude of the virtuous. Do you consciously try not to tip the scales too far in either direction?

Allende: My intention is never to preach. I don’t strike a balance on purpose; that’s the way the story unfolds. I have lived a long life, and in my experience light and darkness always go together, like the principle of photography. How could we know light without knowing darkness?

Chapter 16: Much of Maya’s Notebook takes place in the island province of Chiloé, which you describe as a little world unto itself. What are the advantages of using such a constricted setting?

Chapter 16: Much of Maya’s Notebook takes place in the island province of Chiloé, which you describe as a little world unto itself. What are the advantages of using such a constricted setting?

Allende: I needed to hide Maya in a remote and safe place where her enemies would not find her. Chiloé was the perfect refuge for her. I also wanted to contrast Las Vegas, an artificial city of entertainment, glitter, noise, gambling, prostitution, etc., with a place where Maya can find solitude, silence, and time to reflect and grow up. The archipelago of Chiloé is stunningly beautiful, but it is not paradise; the weather is lousy and there are problems: alcoholism, unemployment, domestic violence, etc. But it offers Maya a safe haven.

Chapter 16: This novel resembles your other novels (the del Valle books, especially) that cover a great geographical range. Your novels demonstrate that the world was “global” long before corporate capitalism became ubiquitous. Do you make your novels international by design, or do your characters naturally become global wanderers?

Allende: I am a global wanderer, as you say. I was the daughter of diplomats; I have been a traveler, a political refugee and now and immigrant. I have no roots, so naturally I am interested in people who live in the margins of the society, the outsiders, the vagabonds. They make great characters in literature.

Chapter 16: Allende fans expect to be thrown into stories involving the consequences of desire, of life-changing passions, and the way they can compel our actions and determine our fates. Is it fair to say that your characters’ unconscious longings tend to overpower their conscious powers of reason?

Allende: I am not a very reasonable or logical person, so it is easy for me to create characters that are blown away by the storms of passion. Often I make decisions by impulse or intuition. Passion can cause terrible problems in normal day-to-day life, but it also fuels great love, heroism, and tragedy, the best ingredients for fiction.

Chapter 16: In Daughter of Fortune you refer to Chileans as a “practical and prudent people,” and yet your characters still find ways to live according to unbridled romanticism. Do you see a divide in the Chilean national character between pragmatism and ardor?

Allende: Yes, there is an interesting divide in the Chilean temperament. I would not say that we are particularly romantic. In matters of the heart women, more than men, tend to be passionate. For everything else, including politics, we are cautious and practical, but when the circumstances demand it we can be fierce. (For example, Chilean soldiers have a reputation for being cruel, reckless, and brave.)

Chapter 16: You have said that you generally do not know why you become obsessed with certain subjects until months after the books about them have been published. Have you discovered yet how Maya’s Notebook is connected to your life?

Allende: I wrote Maya’s Notebook when all my grandchildren and their friends were teenagers. They were exposed to all kinds of dangers—drugs, alcohol, crime, violence, pornography, etc.—and their parents could not protect them. I was afraid for them, and this novel was a sort of exorcism: by writing about the worst scenario, I would keep the demons at bay. In a way it worked because now all those kids are safely in college. They survived adolescence, while poor Maya went through hell. Fortunately for her, however, she was in hell only a few months, and she was rescued just in time. It is no coincidence that her Chilean grandmother rescued her!

Isabel Allende will discuss Maya’s Notebook at the Nashville Public Library on May 3 at 6:15 p.m. The event, part of the Salon@615 series, is free and open to the public. Tickets may be reserved in advance here.