Parallel Lives

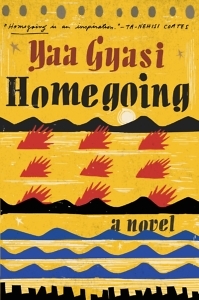

Yaa Gyasi’s debut novel, Homegoing portrays the ravages of the slave trade on both sides of the Atlantic

Yaa Gyasi’s debut novel, Homegoing, tracks the family lines of half-sisters born in Ghana in the late-eighteenth century. Effia becomes the “African wife” of the governor of Cape Coast Castle, the British fortress that serves as a hub of the empire’s slave trade. Esi, who “grew up in bliss” as the cosseted daughter of a village leader, is captured by a rival tribe and sold to the British. Thrown into the women’s dungeon beneath the Cape Coast Castle, she is stacked like cargo for shipment to the American colonies. In alternating chapters, Gyasi charts the fates of Effia’s and Esi’s descendants in Ghana and America over the next six generations.

The novel’s structure invites a question: which side of the slave trade fared better? Is it preferable to live with the physical torment of slavery in America or with the pangs of conscience in Africa, where the leaders of the Asante and Fante tribes maintain their prestige by selling fellow countrymen to Europeans? In harrowing detail, Gyasi describes the exploitation of African labor in the American South, before and after the Civil War, a crime against humanity that bordered on genocide, though the survivors do pass on traits of ingenuity and perseverance that allowed their descendants to enjoy the twentieth century’s liberty. Descendants of the African branch of the family, meanwhile, remain stuck in a feudal system manipulated by European traders to the present day.

Gyasi’s characters are willing to make “unimaginable sacrifices” in exchange for the possibility of freedom, if only for their offspring. One Ghanaian descendant of slave traders fakes his own death to live in principled poverty. In the U.S., two slaves make a bid for emancipation via the underground railway to deliver their son from the hell of the plantation. These characters don’t often win their battles, but their gritty spirit animates each page of this inspiring novel.

When a Baltimore pastor warns a boy against using “African witchcraft,” his guardian, an older woman who remembers the ways of their native land, encourages him to fight back: “The white man’s god is just like the white man. He thinks he is the only god, just like the white man thinks he is the only man,” she says. “But the only reason he is god instead of Nyame or Chukwu or whoever is because we let him be. We do not fight him. We do not even question him.”

Gyasi is clear about the brutality of white Europeans and Americans, but she also highlights the way Africans on both sides of the Atlantic contribute to their own undoing. Time and again racial oppression is exacerbated by regional rivalry, often with dire consequences, as tribal leaders fail to see that their fratricidal raids keep them from fighting against their common enemy. Esi’s daughter Ness (short for “goodness”) suffers at the hands of other slave women who are envious of her strength and beauty. A former slave finds work in a shipyard, helping to build the very vessels that bring his people in chains from their homeland. To overcome tyranny, these characters must do more than fight against the white man; they must learn to collaborate.

Homegoing, whose title refers to a dead soul’s reunion with God, takes on weighty issues but at times exhibits a sense of play. The characters joke and tease one another, and they have sex at every available opportunity. Readers may find the opening pages, with their yam reckonings and palm-wine celebrations, overly reminiscent of Chinua Achebe, but Gyasi’s narration offers a uniquely female perspective on central-African culture. When Ness first encounters the new slave, “straight from the Continent,” whom her overseer has decreed she will marry, “she is in awe of him, for he is the most beautiful man that she has ever seen, with skin so dark and creamy that looking at it could very well be the same thing as tasting it. He is the large, muscular body of the African beast, and he refuses to be caged.”

Homegoing, whose title refers to a dead soul’s reunion with God, takes on weighty issues but at times exhibits a sense of play. The characters joke and tease one another, and they have sex at every available opportunity. Readers may find the opening pages, with their yam reckonings and palm-wine celebrations, overly reminiscent of Chinua Achebe, but Gyasi’s narration offers a uniquely female perspective on central-African culture. When Ness first encounters the new slave, “straight from the Continent,” whom her overseer has decreed she will marry, “she is in awe of him, for he is the most beautiful man that she has ever seen, with skin so dark and creamy that looking at it could very well be the same thing as tasting it. He is the large, muscular body of the African beast, and he refuses to be caged.”

Gyasi’s treatment of history is notable as much for its omissions as for its inclusions. She mentions the American Civil War only in hindsight, for example, choosing to focus instead on the Fugitive Slave Act, one of the vilest provocations of the era. Passed in 1850 as a compromise between the South and the “Free-Soilers,” that law ostensibly required Northern police to apprehend runaways and return them to their overlords. In reality, the Act deputized bounty hunters to roam free states and kidnap African Americans, regardless of their legal status. Former slaves just beginning to enjoy freedom see their families ripped apart and must start from scratch, again.

Homegoing is simultaneously epic and compact, its three-hundred-year scope neatly contained in brisk episodes that enable readers to make connections among the changing time frames and settings. Recurrent motifs—fire, nightmares, infertility—underscore the generations’ common plight. Gyasi has said in interviews that she was inspired to write this novel after traveling to Ghana (her birthplace) and visiting the Gold Coast Castle. The personal nature of the work is manifest in the intimacy of the characterizations and the intensity of her prose. It is no surprise, then, when she uses her family name in a roll call of tribal clans. Homegoing honors her ancestry and deserves to be discussed in classrooms and book clubs alike.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.