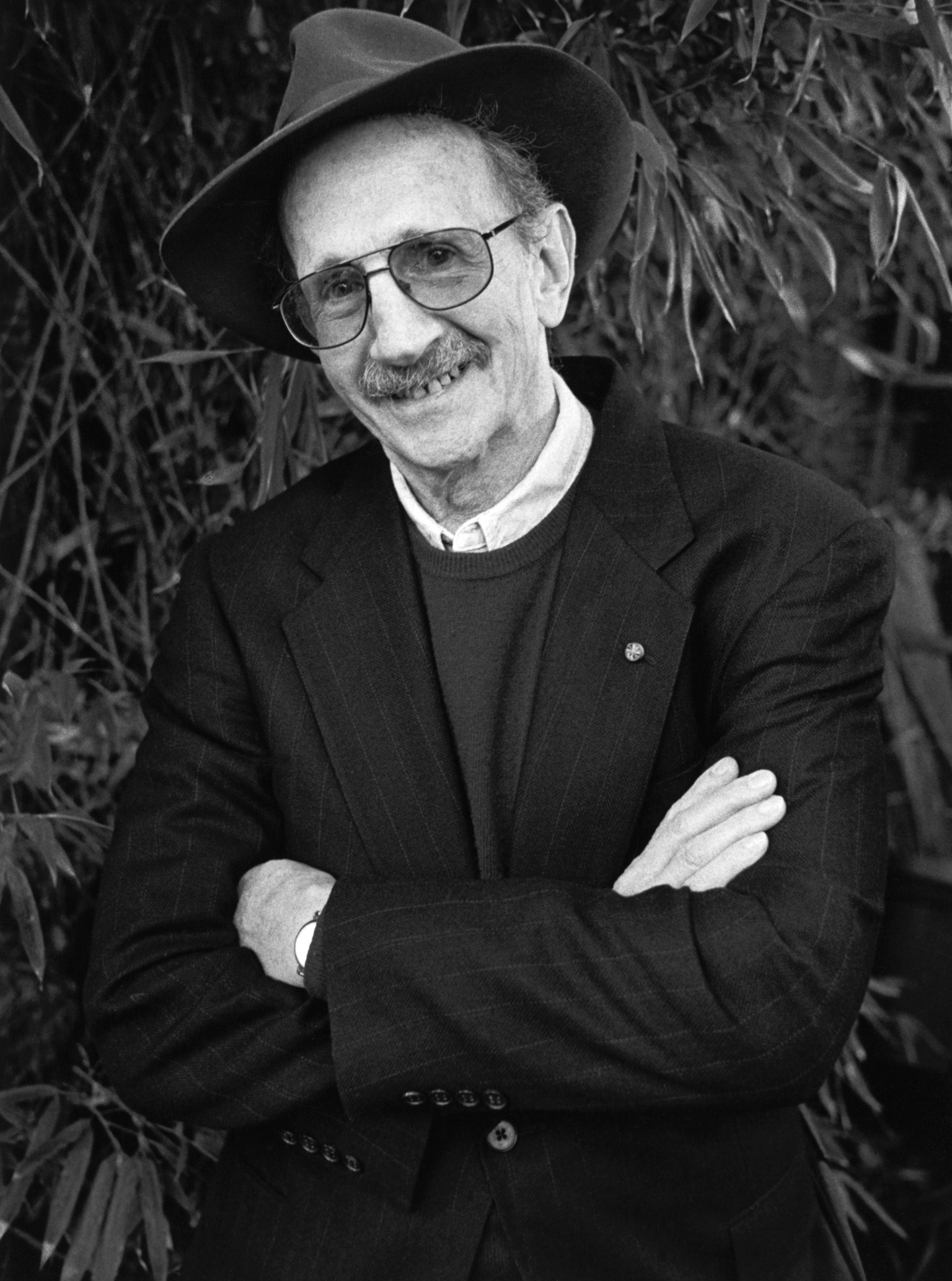

Phil Levine and the Burger Bitch

There once was a Pulitzer Prize-winner who wrote poems about the working-class people most writers never notice

About twenty years ago, when poet Philip Levine was Vanderbilt University’s visiting writer, there was a Burger King on 21st Avenue South, at the edge of the college’s magnolia-fringed campus. It had a large parking lot that butted up next to a place called San Antonio Taco Company, where Vanderbilt students line up to buy galvanized buckets of long-necked beers on ice to ease down their guacamole tacos and buffalo wings. The parking lot belonged to Burger King, but SATCO customers often parked there.

Nowadays, Panera Bread (which has replaced the Burger King) employs a large, male security guard festooned with handcuffs and a police baton to patrol the lot, making sure the spaces reserved for Panera customers go to Panera customers. But back in 1995, Burger King had a sole female employee performing that job. Anyone who’s spent time around college students can tell you it’s dangerous to get between them and their beer. So it was not unusual to see this woman—in her late fifties, early sixties—running out of Burger King in her brown-polyester BK uniform, a matching kerchief flapping around her neck, a matching cap bobby-pinned to her bleached-blond hair.

Nowadays, Panera Bread (which has replaced the Burger King) employs a large, male security guard festooned with handcuffs and a police baton to patrol the lot, making sure the spaces reserved for Panera customers go to Panera customers. But back in 1995, Burger King had a sole female employee performing that job. Anyone who’s spent time around college students can tell you it’s dangerous to get between them and their beer. So it was not unusual to see this woman—in her late fifties, early sixties—running out of Burger King in her brown-polyester BK uniform, a matching kerchief flapping around her neck, a matching cap bobby-pinned to her bleached-blond hair.

Like a lot of people who do these kinds of jobs, she was a good employee, and she took her work seriously. To discourage the students from parking where they wanted to park, she sometimes shook a rag at them; sometimes she just called out. Overwhelmingly (of course) they ignored her. When she wasn’t trying to chase off illegal parkers, her duty was picking up trash. You’d have thought anyone could see it was a miserable job and taken pity. In 1995, she must have been making $4.25/hour, minimum wage at that time—$170/week if she worked full time. Some of the students called her the Burger Bitch. I just hope she never knew.

As it happened, my colleague Vereen Bell sometimes had a cup of coffee and did a little last-minute paper grading in the Burger King before crossing the street to class. It was convenient, cheap, quiet. It’s hard to describe Vereen: somewhere in his late seventies now, he’s an iconic figure at Vanderbilt, where he’s taught for more than half a century. He pretty much transformed the English Department from its midcentury roster of white-men-teaching-white-men into the lively, diversified department it is today.

Vereen is a serious poetry-lover and has done scholarly work on T.S. Eliot, Robert Lowell, Robert Frost, and Yeats. He loves Wallace Stevens inordinately. During the semester when Philip Levine was in residence at Vanderbilt, he and Vereen struck up a friendship that extended to their wives. The four of them—Phil and Fran, Vereen and Jane—had a lot in common and spent time together during those early months of 1995, developing a closeness that lingered after the Levines returned home.

In the English Department, we were thrilled when Phil won the Pulitzer Prize for The Simple Truth on April 18, 1995. He actually took the call in his office with his door open. Vereen was in his own office across the hall, ready with a bottle of bourbon. I was in an office just a few doors down—brand new to Vanderbilt, taken aback by its surface formality and the constraints of a conservative campus culture. “Please be quiet,” warned a placard hung in the hall outside the department. “Voices can be heard from within.” I’d never been part of an English Department where talking was discouraged.

As soon as Phil confirmed he had won (“Yes. Isn’t it sweet?” he said to my colleague Mark Jarman), I watched in astonishment as various faculty and staff rushed up and down the hall, arms full of liquor bottles, or wrapped around trash cans commandeered as ice buckets. Soon a full-blown party was underway in the Department’s Duncan Library. What I remember best is the expression on Phil’s face—bemused, pleased, still something a little bit held back. I read later that he said of the Pulitzer, “If you take it too seriously, you’re an idiot. But if you look at the names of the other poets who have won it, most of them are damn good.” His face reflected those split emotions that afternoon.

As soon as Phil confirmed he had won (“Yes. Isn’t it sweet?” he said to my colleague Mark Jarman), I watched in astonishment as various faculty and staff rushed up and down the hall, arms full of liquor bottles, or wrapped around trash cans commandeered as ice buckets. Soon a full-blown party was underway in the Department’s Duncan Library. What I remember best is the expression on Phil’s face—bemused, pleased, still something a little bit held back. I read later that he said of the Pulitzer, “If you take it too seriously, you’re an idiot. But if you look at the names of the other poets who have won it, most of them are damn good.” His face reflected those split emotions that afternoon.

What does this story have to do with the Burger Bitch, her miserable job, and her pathetic little life picking up trash and chasing drunk college students out of Burger King’s parking lot?

Just this: when Phil gave a poetry reading at Vanderbilt later that semester, Vereen Bell introduced him. The reading was packed. When it was time, Vereen unfolded his tall frame and made his way to the podium. In his slow-paced and garrulous manner, with his soothing, South Georgia accent, he began to talk, bypassing entirely the impressive literary credentials of Philip Levine.

He told, instead, the story of the Burger Bitch, how he had started talking with her one day as she went about her trash-dumping duties. “She came and sat down at the table with me,” he said. “She told me what her job was, and how hard it was, how difficult it was to get the students to listen to her. Then she asked me what my job was. ‘Well,’ I said, feeling a little embarrassed, ‘I teach over there at the college.’ She brightened up right away. ‘You do?’ she answered. ‘Then would you do something for me?’ ‘Sure,’ I said. ‘Would you please tell those girls not to laugh at me because of my job?’”

In the audience, our own laughter, our wry smiles, the subtly self-congratulatory atmosphere we’d created around ourselves at having a Pulitzer Prize-winner on faculty—it all dissipated instantaneously.

For a few seconds—and I will never forget the feel in the room—Vereen let us sit in that feeling.

And then he said, “Maybe you wonder why I’m telling you this story. Well, it’s because it’s the best way I can think of to introduce Philip Levine. He understands how that woman who works in the parking lot at Burger King feels about things. And he writes poems about it.”

Phil Levine would have celebrated his eighty-eighth birthday this weekend, on January 10, but he died last year on Valentine’s Day. Vereen Bell’s introduction—so astonishingly apt, so unique in American poetry—has become Phil’s epitaph.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Kate Daniels. All rights reserved. Daniels, a professor of English, directs the creative-writing program at Vanderbilt University. Her most recent book is A Walk in Victoria’s Secret. It includes “Crowns,” a poem she wrote for Philip Levine. A version of this essay appeared originally as a blog post at Best American Poetry on the occasion of Philip Levine’s death in February 2014.