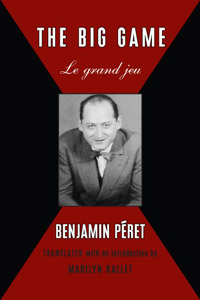

Putting a Mustache on the Mona Lisa

Marilyn Kallet discusses the art of translating Benjamin Péret’s great work of Surrealist poetry, The Big Game

Marilyn Kallet’s lifelong commitment to poetry has led her across both the United States and Europe, where she has performed for and taught thousands of prospective and practicing poets with a charisma borne entirely of her love for the art. Kallet is fluent in French, and the French poets of the late-nineteenth and early-to-middle twentieth centuries occupy a special place in her understanding of the spirit of poetry. She often discusses the work of the legendary Arthur Rimbaud in her classes, and she has translated Paul Eluard’s Last Love Poems. She remains intensely curious about the gems—both hidden and revealed—of French poetry, and particularly French Surrealism.

Enter Benjamin Péret. One of the most important figures in the Surrealist movement, Péret employs a style that is an amalgam of gorgeous imagery, hilarious surprises (such as “A Bird Shit on My Jacket Bastard”), and a unique mastery of imagery, diction, and comparison that plays with and impresses his reader. Kallet’s translation of The Big Game preserves these elements faithfully, which is why it’s such a great read.

Kallet recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via e-mail about Surrealism, Péret, and the art of translation:

Chapter16: What first interested you about Péret?

Kallet: I had previously translated the Last Love Poems (Dernier poemes d’amour) of Paul Eluard, a major Surrealist poet, and that translating was such a meaningful experience for me that I was on the hunt for another French poet to delve into. Four years ago I was rummaging through a Parisian bookstore, and I picked up Le grand jeu. Immediately I liked the unaffected quality of the work, the relatively plain diction, the speed of thought and imagery. I thought I’d try a few of the poems, then I got hooked. Some of the attraction was the quirkiness and humor, the unpredictability of the lines—a challenge for a translator.

Kallet: I had previously translated the Last Love Poems (Dernier poemes d’amour) of Paul Eluard, a major Surrealist poet, and that translating was such a meaningful experience for me that I was on the hunt for another French poet to delve into. Four years ago I was rummaging through a Parisian bookstore, and I picked up Le grand jeu. Immediately I liked the unaffected quality of the work, the relatively plain diction, the speed of thought and imagery. I thought I’d try a few of the poems, then I got hooked. Some of the attraction was the quirkiness and humor, the unpredictability of the lines—a challenge for a translator.

My publisher, Black Widow Press, has brought into print all of the Dadaist and Surrealist poets in bilingual editions, and I suspected that this publisher would provide a welcoming place for my boy Benny (Benjamin Péret). Indeed, Joe Phillips, the publisher, expressed strong interest in this volume. Péret was a good friend of André Breton’s, the founder of Surrealism; and Péret was an uncompromising Surrealist. He cherished freedom of imagination and verbal play over political doctrine. He composed not just poetry but a significant body of essays on art, film, and ethnopoetics. He was a world traveler, fought in the Spanish Civil War though he hated war (his mother had made him enlist in the French army in 1914 at the age of 16). Le grand jeu (The Big Game) is recognized among French poetry lovers as one of Péret’s most important books. It had never before been translated in its entirety, so I found myself with the opportunity to provide what hopefully could be a milestone translation.

Chapter 16: What made this initial interest grow into a professional investment—something that made you want to make Péret available to the American poetry community?

Kallet: Péret’s role in the founding of Surrealism, his championing of Surrealist literature and art, made him seem like an important figure, one who deserved the attention of the international literary community. He was a Trickster, enjoying verbal acrobatics, breaking the rules. But he was more than that. His attention to geography and to flora, his lack of hierarchical thinking (he pays attention to stones and plants in his work as much as to people), his lack of idealizing or objectifying women in his work were a small part of what endeared him to me. At the start of World War II, Péret spent months in solitary confinement, in Rennes, France, for his political activism. During that time he began to compose a major essay on poetry that most French poets are familiar with, Le déshonneur des poétes, published in 1945, condemning the compromises and routines that poetry can sink into.

Chapter 16: Did you encounter any unexpected difficulties with the projet?

Kallet: Initially in translating his poetry, I found his quick turns and changes frustrating. I liked to tell friends that translating him was like translating a squirrel. But eventually he began to whisper to me like an old friend, and his habits of thought and of movement became more known to me. Rarely, for example, does he violate syntax or invent words. There is a fairly clear grid within which his creative antics take place.

He has had an effect on my own poetry, too, laughing at my tendencies to be overly romantic. He plays Mercutio to my Romeo and Juliet, and has had an astringent affect on my lyric poems.

He has had an effect on my own poetry, too, laughing at my tendencies to be overly romantic. He plays Mercutio to my Romeo and Juliet, and has had an astringent affect on my lyric poems.

Chapter 16: For the sake of readers who aren’t familiar with the streamlined connection of images and ideas characteristic of Surrealist style, I’m wondering if you can explain what Péret gains by veiling, or even forsaking, cogent thoughts in his poems and instead focusing on language.

Kallet: Péret doesn’t forsake cogent thoughts or veil anything. He’s much less veiled than someone like Wallace Stevens, for example. There’s no symbolism in Péret—it’s all surface, but the surface is like a painting by Max Ernst or Tanguy. The surface is playful, vibrant, almost palpable material, and very much in love with life itself. Life is movement, and Péret’s work is all about movement. He practiced automatic writing, and that practice shows up in some of the early poems toward the end of this volume. As you know, dreams have their own logic. Péret pays attention to dreams, lets them have their way, honors them, doesn’t try to fix them up.

Many of the poems in The Big Game are built in stanzas, some are structured through incantation or anaphora, rhymed thoughts. This is an ancient, traditional way of structuring, though the contents of the lines or images may be odd or surprising. Surrealists privileged wonder and surprise over logic, dream over exposition, newness over the worn path. Only the surprising or marvelous image is considered beautiful.

Chapter 16: When I was your student at UT, you told our class that translation is an art in itself. Now, with two translations to your name, I wonder if you could elaborate on both what makes translation an art and what guidelines you focus on for producing a faithful translation.

Kallet: The translator must be accurate in rendering the literal meaning of the original text. That means one must know the language from which one is translating, and research any historical or idiomatic terms that may not be obvious. This is very difficult for a translator who is not a native speaker. In translating Péret, I often turned to French friends for help with some of the idioms. Several French poets and linguists helped me when I became baffled. My friend Darren Jackson “spotted me” on the translations so I didn’t commit any bêtises (bloopers).

The translator of poetry must also convey the sense of the original poetry—must convey the lyrical spirit, capture what might be thought of as the musicality of the original. In Péret’s case, one wants to convey an oddness, a quickness, a love of imagery and of transformation, a reverence for the natural world, a sense of humor that defies aesthetic or political correctness. Péret’s humor is dark, but he is very funny.

And hopefully, the translator of poetry will come as close to the sounds of the original as possible. I often counted syllables and always read everything aloud, both in French and in English.

The poetry must read like poetry in the new language, must have the organic quality of a poem, and the more indefinable breath of a lyric. Poets are without doubt the best translators of poetry. The new poem must seem transparent, though. The translator’s personality should not intrude. So the translator is a medium and practices a kind of Negative Capability (Keats’s term), in this case the art of living inside the language of another poet without marring the English version with tics, eccentricities, or ego. Though some people assert that translation is impossible, a lost cause, it’s worth risking failure to capture at least the flavor of the original for the American audience. And at best, the reader can be awakened not just to a poem but to a whole body of literature in lively style that was previously inaccessible.

Chapter 16: Did Péret’s unique style make for more challenging work than other translations?

Kallet: Yes, because there was so much movement, it was sometimes hard to follow the lines. And Péret uses a lot of idiomatic expressions; he plays with them, violates maxims and sayings—like Marcel Duchamp putting a mustache on the Mona Lisa.

Chapter 16: How does the future of Surrealist poetry look? Do you know of any promising poets working in or with the genre?

Kallet: In France, young poets are still working in the vein of Surrealism. I am co-translating a contemporary Parisian poet, Chantal Bizzini, who has been influenced by Supervielle, a very elegant modern poet who was himself immersed in both Symbolism and Surrealism. My co-translators of Bizzini’s work are two younger poets, J. Bradford Anderson of New York, and Darren Jackson, a doctoral student in poetry at UT, who also edits Grist: The Journal for Writers. Darren has translated Surrealist poet Michaux’s Life in the Folds (La vie dans les plis) and his work has brilliant streaks of Surrealistic imagery in it. Darren Jackson and I will talk about translating Surrealist poets at the Southern Festival of Books this October. And on October 5, [at] 7 p.m., Darren, Brad Anderson, Rose Becallo Raney, and I will read “French-flavored poetry” at the University of Tennessee Hodges Library.

Will American readers appreciate Péret? Culturally, Americans tend to be practical people. We don’t much care for dreamers or daydreamers; our work ethic is still that of the Puritans, as is our view of the body. The Surrealists were great dreamers and love poets, and their influence on modern arts has been transformative. American viewers looking at Picasso or Miró or Paul Klee are enjoying the colorful fruits of Surrealism. The latest Woody Allen movie, Midnight in Paris, may help to revive an interest in Surrealist poetry and art. I hope so!

If American literature has been slower to appreciate Surrealist literature than painting, this is also in part because of the lack of availability of texts. By translating a whole book by a Surrealist poet, Benjamin Péret, I’ve given our readers a chance to taste, devour, and to decide if the work speaks to them.

I’m excited about the July 16 launch reading from the new book at Union Ave. Books in Knoxville, and predict that there will be some Surrealist surprises and antics at the venue. Definitely there will be some vin rouge for a toast! Péret never imagined he’d be kicking off the Poets3 series at Knoxville’s new independent bookstore. The other readers, Jeff Daniel Marion and Donna Doyle, while not Surrealists, are poetry rock stars—and it will be an honor to perform poetry at the venue with them.

MarilynKallet will read from The Big Game on July 17 at 3 p.m. at Union Ave. Books in Knoxville. To read a poem from Kallet’s own recent collection, Packing Light, click here and here.