Reading Knockemstiff

Donald Ray Pollock takes Chapter 16 on a tour of the Ohio mill town where he worked for decades before turning to fiction

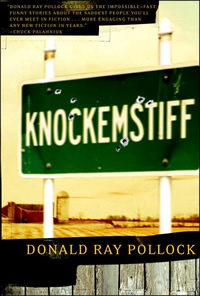

It seemed unlikely that Donald Ray Pollock’s debut collection, Knockemstiff, published in 2008, would cause much fuss in the literary world. Its eighteen stories feature a cast of characters so unseemly and depraved, so lacking in common sense or decency, that the book was sure to sell a few copies to a few weirdoes and be forgotten. But Pollock’s voice is so assured and his vision so precise (and his humor so black) that critics couldn’t help but praise the book as a minor masterpiece.

Even The New York Times weighed in, comparing the collection favorably to another Midwestern story cycle, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. The Times did note, however, that while Anderson’s characters’ depravity was hidden beneath socially acceptable veneers, Pollock’s characters “wear their grotesqueness high up on their sleeves.” Knockemstiff features addicts of many kinds, drunks, kidnappers, prostitutes, child molesters, wife beaters, child beaters, and a mother who makes her son act out sexual fantasies in which he pretends to be the mass murderer Richard Speck. Pollock manages to refrain from both judgment and sentimentality, allowing the exact amount of grace necessary to keep his stories honest and, almost miraculously, free of cynicism.

Knockemstiff‘s popularity wasn’t hurt by the feel-good backstory of its author. Born and raised in the actual Southern Ohio holler of Knockemstiff, Pollock dropped out of high school to work in a meat-packing plant. After a brief time in Florida, he returned to Knockemstiff and spent the next thirty-some years at the paper mill in nearby Chillicothe. Taking night classes, he earned an English degree from Ohio University, and he learned to write fiction by typing out the stories of authors he admired: Denis Johnson, Flannery O’Connor, Ernest Hemingway. He published his first story, “Bactine,” when he was fifty-one, in the literary journal at Ohio State University. The editor was so impressed that she convinced him to enroll in Ohio State’s M.F.A. program. Two years later, Knockemstiff was published.

Now Pollock’s first novel has been released. Set in both Knockemstiff and Appalachian West Virginia, and along the highways of the Midwest and the South, The Devil All the Time weaves together three interlocking narratives and spans the time between the end of World War II and the 1960s. One strand features Willard Russell, who, having survived the horrors of the war, now feverishly tries to save his beloved wife Charlotte from cancer by making blood sacrifices at his prayer log out back. Another strand follows the married couple Carl and Sandy, serial killers who pick up hitchhikers only to photograph and kill them. The final strand centers on the preacher Roy and his crippled cousin Theodore, who, having failed to bring Roy’s wife back from the dead (after murdering her), go on the lam for the next two decades. The heart of the book, though, is Arvin Russell, the son of Willard and Charlotte, who, like many of Pollock’s characters, tries like hell to escape his fate.

I interviewed Pollock the week The Devil All the Time was released. He drove me around Chillicothe and then into Knockemstiff. We talked as he drove.

Chapter 16: So when you’re answering questions now, do you feel you’re on the spot, or have you been doing it long enough to feel comfortable being interviewed?

Donald Ray Pollock: I’m nervous. Because you never know what these people are gonna ask you. And I’m not really that good at explaining. I get asked questions that I really have no idea on how to respond.

Donald Ray Pollock: I’m nervous. Because you never know what these people are gonna ask you. And I’m not really that good at explaining. I get asked questions that I really have no idea on how to respond.

Chapter 16: Like what?

Pollock: Well, this older guy asked, “While you were writing this novel, you know, the novel’s very violent; what did you learn about violence while writing this novel?” I just had no idea. I mean, I don’t think I learned anything.

Chapter 16: Well, the violence in these books is impossible to escape. In the novel, Willard comes back from a pretty horrific experience in World War II in the South Pacific, where he sees a buddy skinned and hanging from a tree like Christ. And his comment is like, “Well, where I come from in West Virginia is bad, but it’s not that bad.”

Pollock: There’s a lot of violence.

Chapter 16: The story is set in that period we normally think of as being America’s Golden Age—Eisenhower, the middle class, America the superpower, high standard of living. But for the characters in your books, it’s a totally different world. So why that time period?

Pollock: Well, I just think that I feel more comfortable writing about that period. Say from the early fifties through the seventies. I just feel real comfortable. And probably, too, I’m a little nostalgic for that time.

Chapter 16: That’s funny. You know, for someone who has read your books to hear you say you’re nostalgic.

Pollock: My dad had a job, he had a good job; we would have been considered middle class. But most of the people I grew up with were not. They didn’t see any of those boom times, I guess you might call them. And you know, when LBJ started the social programs, Knockemstiff was one of the places where they sent a guy to help build a baseball diamond so the kids would have somewhere to play.

Chapter 16: Right, right, America’s in the boom times, but there are social programs. So the social-program guy shows up in Knockemstiff , and—in your story, anyway—the guy they send molests a kid, right?

Pollock: There were people, like my dad, who worked at the paper mill; several people out there had fathers who worked at the paper mill. I think maybe one or two worked at the prison. One or two worked at what they called the atomic plant down in Piketon. So there were some people with some good jobs. But then there were a lot of people, I mean, I really don’t know how they were living. Their dads didn’t seem to work, or not very much. Then there were others who, they just worked on a farm. Of course that was a period when you could still farm. A farmer might hire a dozen people every once in a while. Bring in the hay or whatever.

Chapter 16: Are you aiming in your work for a kind of social history?

Pollock: You know, with this book I guess maybe my aim was; I wasn’t aiming for anything literary. I was aiming for—you know, I wanted this gritty sort of crime-story type thing that just kind of reads fast and that maybe people will keep reading.

Chapter 16: So the serial killers, and the hitchhiking theme.

Pollock: I hitchhiked a lot back then.

Chapter 16: I hitchhiked up and down California. And you do run into the freaks. I’m not saying you always run into serial killers. What was the guy’s name in Chicago?

Pollock: Gacy? I read a book on him before I started this book. He killed one or two in the late sixties, but then it was in the early seventies that he went on his big spree. He killed mostly hitchhikers. Of course not all, but most of them were hitchhikers. And then there were a couple guys out in California doing that in the seventies.

Chapter 16: Yeah.

Pollock: Carl and Sandy just started a little earlier, I guess.

Chapter 16: In the “Rainy Sunday” story in Knockemstiff, there’s Sharon and her aunt, who are picking up men, and the aunt may or may not be killing these guys.

Pollock: Yeah, I wanted to leave that open.

Chapter 16: So are Sharon and her aunt models for Carl and Sandy? Did you have them in mind when you started thinking about the novel?

Pollock: No. The only character in The Devil All the Time that survives from Knockemstiff is Hank.

Chapter 16: The storekeeper.

Pollock: Right. And other than him, I wasn’t really thinking too much about that other book. I was trying to get it right as far as Hank goes, but that’s about it.

Chapter 16: Didn’t your family own a grocery store?

Pollock: Yeah. I’ll show you.

Chapter 16: And is that the model for Maud Speakman’s place, where Hank works?

Pollock: Yeah. But there was also a woman who owned another grocery store about, oh, three miles away. And her name was Maud. It wasn’t Speakman, but it was Maud something else. It started with an S, though.

Chapter 16: Did you used to work in your family’s store when you were a kid?

Pollock: Oh yeah. A lot.

Chapter 16: Did you sell a lot of baloney?

Pollock: We sold a lot of baloney.

Pollock: We sold a lot of baloney.

Chapter 16: Because baloney comes up over and over again in your stories and in your novel.

Pollock: Baloney’s a staple.

Chapter 16: There’s baloney. Hot dogs show up all the time. And paper-bag disguises.

Pollock: No prime rib in my books.

Chapter 16: No, no prime rib. And photographers. You’ve got a thing against photographers.

Pollock: I was just winging it, man. You know? I mean, what do they do with these hitchhikers? I wanted Carl to be this guy who sat around the apartment all the time—

Chapter 16: He’s ugly. And sort of festering. As opposed to these beautiful people going out and doing this stuff. What’s the Oliver Stone movie?

Pollock: Natural Born Killers.

Chapter 16: Right. Where you have two of the most beautiful people in the world running around killing people. But Carl, especially, is just a gross individual.

Pollock: There’s a cousin of mine. See that guy on that mower?

Chapter 16: Yeah.

Pollock: There was that Brad Pitt movie, Kalifornia. Did you ever see that, where he’s a serial killer?

Chapter 16: I don’t think so.

Pollock: It’s actually pretty good. And he’s got this woman with him. But I just don’t look upon those—in my head, I don’t see serial killers as being beautiful people.

Chapter 16: Except, who was it, Ted Bundy?

Pollock: Ted Bundy was. He was handsome guy.

Chapter 16: So what road are we on now?

Pollock: We’re on Huntington Pike.

Chapter 16: Were you worried about The Devil’s critical reception?

Pollock: I was nervous.

Chapter 16: It’s getting pretty freaking good reviews.

Pollock: Well, yeah, I can’t complain about the reception. I’ve only had what I consider one bad review and that was with Kirkus.

Chapter 16: And then the Boston alternative weekly, The Boston Phoenix. Did you see that one? The guy said you were just going over the top unnecessarily.

Pollock: I haven’t seen that one. I got a good one in that magazine, I don’t know if it’s in San Francisco or Portland, that magazine called Zyzzyva? I got a good one in there. It was really good. And I got a good one with the Dayton paper and the Columbus paper and all that. And because I got a couple that were pretty decent before I got that Kirkus one, it wasn’t so bad. The one I’m really concerned about is The New York Times . That one, and, see, I did an interview with Terry Gross.

Chapter 16: Nah.

Pollock: Yeah.

Chapter 16: You were on Terry Gross? Oh my God, dude, you did Terry Gross?

Pollock: I was not mentally in good shape that day. I wasn’t thinking very well. So I don’t know how it’s going to turn out.

Chapter 16: She knows how to edit.

Pollock: They’re going to have to edit her as much as me, almost, because she would start a question and then she’d say, “Stop. Let me reword that.” And then she might start it again, and then she’d say, “No, no, that’s not it.” Then she’d do it again. The interview was an hour, and it was to get, I don’t know, twenty minutes.

OK, we’re getting into Knockemstiff.

Chapter 16: OK.

Pollock: She said it would be [on] the week of the eighteenth. I won’t even know because I’m going out west Monday morning and I don’t carry a cell phone and I don’t bring a computer or anything.

Chapter 16: You won’t be picking up any hitchhikers going down Highway 1, will you?

Pollock: Man, there’s no way I’d pick up a hitchhiker these days.

Chapter 16: So Terry Gross. You’ve made it. That’s bigger than The New York Times.

Pollock: But the thing is, I don’t know how I came off in the interview. OK, now wait a minute. We gotta stop for a second.

Chapter 16: Oh, wow. This is The Shady Glen Church.

Pollock: Yeah. See this house over here, back here? That’s where I grew up. OK, see that building there, with the green, kinda light green building? We’ll go up here and turn around.

Chapter 16: So this is the Shady Glen—

Pollock: This is the church. Church of Christ in Christian Union. Last time I talked to my old man, he said there’s maybe seven or eight people going there now. That place used to be packed when I was a kid. So this is what we consider the holler. When I was growing up, there weren’t any trailers up here. There were like two houses up there. I mean there were houses—matter of fact, I think there might have been one right up in there. But that house of course was there when I was growing up.

Pollock: This is the church. Church of Christ in Christian Union. Last time I talked to my old man, he said there’s maybe seven or eight people going there now. That place used to be packed when I was a kid. So this is what we consider the holler. When I was growing up, there weren’t any trailers up here. There were like two houses up there. I mean there were houses—matter of fact, I think there might have been one right up in there. But that house of course was there when I was growing up.

Chapter 16: So this is the road on the map in the front of Knockemstiff?

Pollock: No, it’s this road.

Chapter 16: Oh, right. Now I’ve got it. So Slate Hill would be up here.

Pollock: So right in here, when I was a kid, you could go up through there, but it was bad. I mean the road was really bad. So the school bus would come up here and it would turn around. See, this was all different; the school bus could turn around. And there were about seven or eight houses right in here. And one family, they were so poor, man, it was like they had chickens roosting in their kitchen, chicken shit all over the place. It was just really bad. Now most of those houses, probably all those houses, have been torn down. And other people have bought this land up and done their own thing, I guess. But you can go on up this road and you’ll hit Bishop Hill at the top. You’re not missing anything if we don’t go up there. All you’re missing is more trailers. See, I was born in ‘54, and when I was born, there was a place called The Bull Pen, which was right here.

Chapter 16: Right here? And so this was the bar?

Pollock: This is how much this hill has shifted. This guy sold beer and booze in there, I think cigarettes. That’s about it. But he had this set up where there were picnic tables, a horseshoe pit.

Chapter 16: Just like in the book.

Pollock: Just like in the book. But I picture it differently than what it is. But he closed that place I think right around 1956. Something like that. 1957. And then where this trailer is here, there was a house set there. There was another house set right down from it. There was a house set right here. That guy I told you was my cousin? On the lawnmower? He grew up right here. And there was a house set there. There were a couple houses back here. But anyway, this is the store, OK?

Chapter 16: Yeah. That was the store you owned.

Pollock: That was the store we owned.

Chapter 16: And that’s the actual house you grew up in?

Pollock: That’s the house I grew up in. My dad owns—see back beyond that fence where those trees are? He owns the strip from here to over there, all the way back to the top.

Chapter 16: Is he retired now?

Pollock: Oh yeah. He’s eighty-one years old.

Chapter 16: What’s he think about all this, the books?

Pollock: It’s nothing to him. It’s like my old man, he’s sort of one of these guys.

Chapter 16: You have brothers and sisters?

Pollock: Yeah. I’ve got two sisters and a brother. I’ll show you where a couple of them live. But OK, then, the Mitchell Flats—

Chapter 16: So help me with this. I’m trying to figure out where Willard—

Pollock: OK, let’s go back this way.

Chapter 16: Where Willard’s got Arvin up there doing the animal sacrifices.

Pollock: Well now, Mitchell Flats was actually to the right over this way. And what it is, is you get up there on top of that hill, and it’s flat. There was a huge field up there when I was a kid. So we won’t be able to see that but I can take you to where I consider what would be where you pull into Willard’s driveway going back to their house.

Chapter 16: What do your brothers and sisters think?

Pollock: Well, my brother is—we get along OK, but my brother’s been through some rough times. And he’s, you know—

Chapter 16: He’s not clean?

Pollock: No, he’s not clean. But he’s one of these guys that just works and he’s not married now or anything. He’s been married once and been divorced. He lives by himself. But my dad is one of these guys who, you know, to him, being successful is you own your own farm, you’ve got your own business. Writing books is like, ugh, why would anybody spend their time doing that? And we really, we just don’t talk about it. He’ll ask me where I’m going next and stuff like that, but he doesn’t—he’s never read anything.

Chapter 16: He hasn’t read any of it?

Pollock: He doesn’t read any of it. My mom has. But my dad, no. I think my dad’s a little afraid of what he might find in it. I don’t know.

Chapter 16: Does that surprise you, that he’s not interested?

Pollock: No. I knew. And it’s not like it bothers me. I just as soon he didn’t read it.

OK now, this is Baum Hill. Right up here there’s a driveway. We can’t go up in there. These people that own it now, I guess they’re really paranoid about it. But this went up to an orchard, OK? And this is, in my head, this is where I’ve got the house Arvin lived in, up on top of this. And it kind of overlooks Knockemstiff. That’s pretty much it.

When I was a kid, this was an orchard, and the guy who ran the orchard—this is where truth mixes with fiction, I guess—an old man ran this orchard. He didn’t own it, he just ran it. His name was Harry White. And Harry was a very good, decent, religious man. I mean, he really was. And he—him and his wife—took in all these orphans; took care of them, stuff like that. And every once in a while, Harry would go out into the woods and pray in the evenings for about fifteen or twenty minutes. And he would be really loud. And so if the wind was just right, you couldn’t hear the words, really, but you knew that he was up there praying. And that’s where the idea of Willard and the prayer log came from. Now Harry of course didn’t have a prayer log or an altar or anything like that.

Chapter 16: He wasn’t sacrificing dogs and lawyers.

Pollock: Right. He’d just walk down in there and pray for a little bit. And it seemed like it was right around suppertime.

Chapter 16: That’s a powerful part of the book.

Pollock: And like I say, all this was different. There weren’t any houses here. And over there, those old ones have been remodeled.

Chapter 16: What do your sisters think about all this?

Pollock: My sisters are real supportive.

Chapter 16: What do they do?

Pollock: Well, one of them, her husband works at the paper mill, and she runs a cleaning business. You know, goes in and cleans peoples’ houses. She’s got her and a couple other women that work for her. And then my other sister—she’s not married—and she works in a store in town that sells bread and baked goods and stuff like that, and she’s worked there for, ah, shit, I don’t know how long. Twenty-some years, I guess. Now she lives out here in a house that my great-grandfather and my great-grandmother lived in. And then my brother lives behind her in a double-wide.

Now this guy here is really the only farmer, big farmer, we’ve got left.

Chapter 16: Right there?

Pollock: Yeah. He farms a lot of land. Now as you can see, my dad’s house is right here past this next one, this blue one. There’s about eighty-some acres in there. He’s got a hell of a nice pond back in there.

Chapter 16: What happened to the store?

Pollock: My sister’s got three daughters. Two of them have been married and divorced. Well, one of them sort of took the store and fixed it up and started living in it for a while. Then she moved out, and other one moved in.

Chapter 16: Keeping the store open?

Pollock: No, just living in it. So now the third one, the youngest one, is living in it.

Chapter 16: Has anyone in your family ever left Knockemstiff, or left Chillicothe? Left the area?

Pollock: My immediate family? No.

Now all this through here, on both sides, there was none of this, none of these houses.

Chapter 16: And was it grown up like this with trees, or was it clear?

Pollock: Well, this was a field, and this was like a swamp. In fact this place right here, that was called Foggymoore. None of these houses were here. Now this house was here. It was the guy that owned all the land from here to my dad’s.

Chapter 16: Wow.

Pollock: There was over a thousand acres. Then he sold it. He sold all of it. And these houses weren’t here. But there were other, older houses, beat-up houses. I’ve got some cousins that live there. And they’re in bad, bad shape. I mean they’re wasting. My sister lives in that one there; that was my great-grandfather’s house. And my brother lives back there in that double-wide, like I said.

Chapter 16: Are you still in touch with people from when you were a kid?

Pollock: Oh yeah. Not very many. Now, my cousins? I mostly ran around with those guys when I was younger, but I don’t go around them at all now.

Chapter 16: How long have you been clean?

Pollock: Since 1986.

Chapter 16: Well, the people you hang around become different, right?

Pollock: Well, yeah. I mean, I ran around with those guys up until then. You know, I was working, and they never did work much, but I always worked. But I still hung around with them a lot. Well, probably until the last, until the last couple years I was drinking, and then I wasn’t really hanging around too many people at all.

Chapter 16: Well, your depiction in these books of alcohol and drugs are so exact, and without any of the sentimentality or histrionics.

Pollock: A lot of people—I can understand why they do it—but they sort of romanticize it, you know. I’m sure that some people think, “He’s just using that ‘I used to be a drunk thing’ as part of his gimmick,” but I try to make people understand that there was nothing romantic or exciting about this. It was freakin’ miserable to live like that.

I met some crazy people, no doubt. Most of them I was afraid of. There was this one bar the last couple of years I was drinking. The name of it was The Big Penny, and I would go in there on Sunday nights, and in Chillicothe on Sunday nights a lot of the bars were closed down and especially at one o’clock in the morning. But the Big Penny was open till 2:30, so I would always go down there at some point on Sunday night. And I remember the last year I was drinking, every time I walked into that place I had this feeling come over me that, man, something bad is going to happen if I keep coming in here. It was the worst of the worst, that bar, and part of it was I think my paranoia by that time had gotten serious.

So we’re on Route 50, heading back to Chillicothe.

Chapter 16: The idea of these road books, which is what your Devil is, in a sense—it’s a road book. These characters all leave and start travelling and start moving. But just like in Knockemstiff, they all come back, and none of them gets away; nobody gets away.

Pollock: Yeah, Arvin ends up back in Knockemstiff.

Chapter 16: Yeah, exactly. The only characters who ever end up leaving Knockemstiff, even in the short stories, die. The only one I can think of who doesn’t die is the sister of Charlotte; she takes off, and nobody ever hears from her again. So if you do make it out, you die. And the only outside forces that come into Knockemstiff are the do-gooders from the government, and they molest the children. So it’s kind of like this closed-off world.

Pollock: Well, when I was writing this book, I guess I wasn’t really thinking of themes. You know, I just had these characters and I wanted to somehow weave several different story lines and I wanted to somehow connect all these towards the end. And I had this vague idea of how I wanted to end the book. So for me it was like a nuts-and-bolts type thing. I mean OK, so Roy’s going to meet Carl and Sandy, so what’s going to happen to Roy? You know, his daughter is dead, and he killed his wife. It’s only logical that Roy dies, too. He doesn’t make it back to Coal Creek.

Chapter 16: Of course not.

Pollock: So a lot of that was just plot devices. Other people, readers, can see things in a book that the writer can’t.

Chapter 16: I don’t think you were thinking, “OK, they’ve left Knockemstiff; now I have to kill them.” But I do think it’s sort of interesting that in all the stories you’ve written, without thinking about it, that is what happens.

Pollock: Right, and that could just be, unconsciously, when I was growing up and when I was a young man, I always wanted to be somewhere else. You know, after I cleaned my act up, I started accepting myself for who I was and I became satisfied. This is who I am. And I’m pretty much satisfied with just staying here. But you know, I have thought about maybe trying to move away. Especially since my wife’s retired. But I doubt if I do.

Donald Ray Pollock will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.