Religion and Dogs and Woods

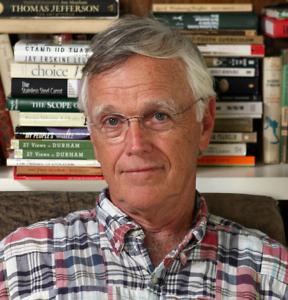

Clyde Edgerton talks with Chapter 16 about the Southern literary landscape

Few contemporary Southern writers have enjoyed the success of Clyde Edgerton. Beginning with Raney in 1985, he has published ten novels and two works of nonfiction. Three of the novels have been made into films and seven adapted to the stage, and he has earned a long list of accolades and awards. Raney and another of Edgerton’s early novels, The Floatplane Notebooks, have just been reissued by the University of South Carolina Press in its Southern Revivals series, which celebrates “the astonishing diversity of contemporary Southern culture.” In these novels and others, Edgerton’s characters are almost universally Southern, almost always funny, and astonishingly human—even the nonhuman ones. Prior to his appearance at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville, he answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: The Southern Revivals Series is dedicated to deepening readers’ understanding of and appreciation for “the flourishing Southern literary landscape.” How has that landscape—and perhaps what it means to be a Southern writer—changed with twenty-first-century influences like cable news and social media?

Edgerton: I think all these new things must fit into scenes that are written by fiction writers about contemporary life, and therefore, in a sense, if you are writing about contemporary American life, it pays, in some ways, to be young. I’m writing about a twenty-five-year-old character these days for a novel, and I have a couple of twenty-five-year-old people advising me. So, to the question that was asked: the landscape is ever-changing and as long as memory and community and love of words and turns of phrase and hot weather and religion and dogs and woods and issues about ethnicity and identity are a part of some writer’s life, there will be what is called a Southern literary landscape. These days, the new writers are diverse and modern, but there are echoes of those Southern norms and habits and ways of being that can nurture and embrace a human being, as well as those that repel and wound a human being. Paul Kwilecki said it better in his book called One Place. Louis Rubin also says it mighty well in the afterword to the second edition (1991) of The American South: Portrait of a Culture.

Chapter 16: Your protagonists and narrators include men and women, young characters and old, dogs and wisteria vines. What draws you to inhabit such continually varied lives?

Chapter 16: Your protagonists and narrators include men and women, young characters and old, dogs and wisteria vines. What draws you to inhabit such continually varied lives?

Edgerton: Remembering where there has been heat in my life—love, despair, hate, loss, hope, fear—and getting a kick out of inhabiting the imagined lives of made-up fiction characters (who may resemble relatives and old friends) is kind of what keeps me writing fiction.

Chapter 16: Of all the characters you’ve created, which are your favorites?

Edgerton: Gosh, if I could have dinner with several, it’d be with Bliss Copeland (The Floatplane Notebooks), Meredith Copeland (The Floatplane Notebooks), Cobb Pittman (Redeye), Uncle Hawk (The Floatplane Notebooks), Larry Lime Holeman (The Night Train), L. Ray Flowers (Lunch at the Piccadilly), Gloria Palmer (In Memory of Junior), and Wesley Benfield (Walking Across Egypt). Then I’d like to pick new bunches for occasional dinners in the future.

Chapter 16: In new introductions to both Raney and The Floatplane Notebooks, you describe the way each novel arose from events within your own family. After a dozen books, how has your extended family adapted to its occasional appearance in fiction?

Edgerton: I’m lucky in that those who’ve read the novels have (or had) a clear understanding that fiction is (in Robert Penn Warren’s words) “a made-up story about made-up characters.” I tell students who don’t want to base a character on their mother for fear of being caught red-handed to just have the mother-like character shoot a dog or kill somebody in chapter two, and then suspicion from Mama will evaporate. She will know it ain’t her.

Chapter 16: You’ve spent four decades teaching young writers. Has teaching informed your own approach to craft in any significant ways?

Edgerton: Let’s see. I hope it’s made me more apt to follow my own advice, a main part of which is “Follow no advice that doesn’t make sense to you” and “Write for yourself as audience.”

Chapter 16: Reviewers praise your characters for their complexity, and they can be funny as all get-out, yet most tend to speak in sentences of two or three words. How important is simplicity to good storytelling?

Chapter 16: Reviewers praise your characters for their complexity, and they can be funny as all get-out, yet most tend to speak in sentences of two or three words. How important is simplicity to good storytelling?

Edgerton: I wanted to answer: very. But I’ve been reading some amazing Faulkner recently (in the middle of The Hamlet when Mink stuffs a corpse down a hollow tree), the pages aren’t exactly simple, and so, hmmm…. In many situations, making it simple is good in that simplicity allows the perceptive reader room to participate in the story.

Chapter 16: Like other Southern writers before you, your books and characters struggle with issues of race. Do you hold out any hope that literature can find a way to help bridge a racial divide that seems as wide now as in the days of Faulkner and Welty?

Edgerton: I think a reader is often able to find empathy with fictional characters (and fiction writers) who are different (race, sex, gender, outlook, beliefs, values, habits, etc.) from the reader. I believe this empathy with “different” fictional characters and writers, in turn, ups the chances of reader empathy in real life. A goal, of course, is that “difference” loses its edge, and we begin to discover and understand ways we are alike—in spite of the ease with which pre-judgement slips into our noggins.

Michael Ray Taylor chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction.

Glen Rose copy_0.jpg)