Relinquishing the Flimsy Protection of Shelter

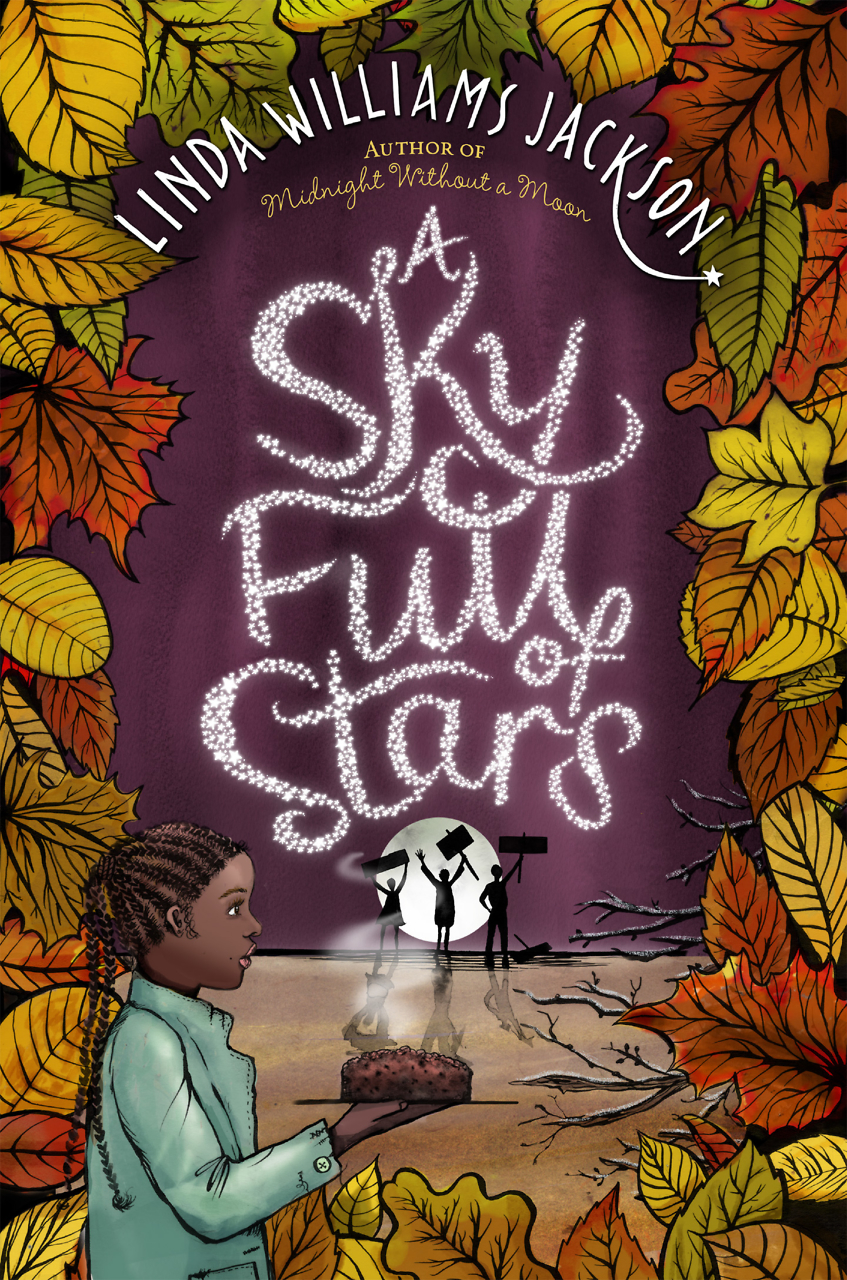

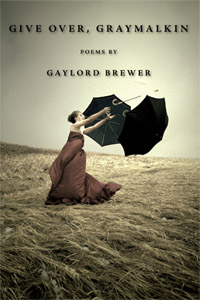

Gaylord Brewer discusses his eighth collection of poems, Give Over, Graymalkin

Gaylord Brewer’s eighth collection of poems, Give Over, Graymalkin, delivers gripping, meditative poems that take readers to unexpected places—India, Spain—or simply make them see their own back yards in a new way. Smart, quirky, and sensual, these poems on longing and loss speak directly to our times.

Brewer has published over 800 poems in journals and anthologies, including Best American Poetry and The Bedford Introduction to Literature. Brewer is also a playwright, and his plays have been staged in New York, Chicago, and Nashville, among other cities. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, he is currently an English professor at Middle Tennessee State University and the editor of the journal Poems & Plays. In 2009, he received the Individual Artist Fellowship in Poetry from the Tennessee Arts Commission. He recently spoke with Chapter 16 about the challenge of writing in a foreign country, his advice for young poets, and the pleasure of writing rude poems.

Chapter 16: The title of this excellent collection is taken from a longer quotation of a passage by Cormac McCarthy that also serves as your third section’s epigraph: “Give over, Graymalkin, there are horsemen on the road with horns of fire, with withy roods.” How do you see that passage as a way to unify the poems in this latest book?

Brewer: First off, despite Oprah’s book club, I adore McCarthy’s work and am generally fond of epigraphs that make me sound smart. With the exception of one section, I believe this to be a rather dark collection, with lots of poems about loss and leavings. I like the edgy, aggressive, apocalyptic warning of the quote, which, by extension, sounds a discordant note with the book’s gorgeous cover photo. A happy accident. Dance in the wind in your loveliness and youth. Relinquish the flimsy protection of your shelter. Darkness comes and, faint yet distinct, the hooves of the rider approach. Plus the words just sound great out loud. Say them. Mm, that’s mouth-feel.

Chapter 16: The collection opens with a quiet, gripping poem titled “After,” which ends this way:

What was a life worth,

beleaguered friend,

when you finally returned,

stinking, unshaven,

parched all the way through?

Dark doorway and key,

hand pushing forward,

one step across to silence.

“Silence” is an interesting word choice for the opening of a poetry collection. How does this first poem establish the themes of the book?

“Silence” is an interesting word choice for the opening of a poetry collection. How does this first poem establish the themes of the book?

Brewer: As I mentioned, there are lots of departures in this book, and a few ambiguous returns as well. Our log house in the woods lost its magic for me for a while after we buried our sweet old dog Jasper, so I was traveling more than ever. And if your language is dodgy, or even if you’re home but feeling a little raw and withdrawn, you—meaning me—may spend a lot of time in your own head talking to yourself, to some schlemiel who has no choice but listen. That is to say, silence. Plus, I’ll admit I like that poem and wanted to start off with a good one.

Chapter 16: In your acknowledgments, you mention writing residences in France, India, and Spain, and the poems in this collection really do place the reader in those countries. One of your most vivid images is a scene in which the speaker is standing in a shared kitchen, wearing woolen socks and sandals and trying to figure what to do with the rabbit he has just purchased: “Again I got what I’d claimed / to want—how to get rid of it?” he asks. Could you talk about what you gain from working at residences abroad and what that experience does for your work?

Brewer: That rabbit ended up quite tasty, with a lot of sliced garlic and fresh paprika, but it was a mess for a while. A metaphor or just a fine meal? I’ve been lucky to travel a lot and have a lot of residencies, and it so happens that the majority of poems in this book were indeed written in India, Spain, and France, thanks to the enduring patience of a number of kind and odd folks. Lord, how I suffer. Wonderful experiences and inspirations, but also those attendant moments of dislocation, darkness, exhaustion bought and paid for. Why does the weary traveler put him or herself through such travail? Toward what? Away from what? On a more practical front, it’s fun to jump into nervous situations and then insinuate or bullshit or buy your way out. A month or more away from work, distraction, American convenience, with only the excuse of writing a poem each morning—wonderful, if you can carry the load.

Chapter 16: For readers who might want to travel and write—or who have—do you have any suggestions of what not to do when writing about foreign places?

Chapter 16: For readers who might want to travel and write—or who have—do you have any suggestions of what not to do when writing about foreign places?

Brewer: Obviously the biggest challenge is not to write “travel” or “vacation” poems, a tepid travelogue, or to embrace some faux expatriate nonsense about jazz clubs and flappers and despair. Since I’m always only thinking about myself, I hope I’ve gotten well-practiced in bringing my little bag of obsessions and complaints along with me, so I can, on a good day, fold the landscape and adventures and embarrassments right into a perspective that challenges what I pretend to know about how we live.

Chapter 16: In many of your poems, you make this particular move that is hard to describe but it is very “Gaylord Brewer”: you’ll be describing a scene or an object up close and then you’ll make a tonal shift that is unexpected, and the poem often moves to a darker place, one of close critical introspection. I’m thinking in particular of “Jungle Appetites” right now…..

Brewer: Well, when you suddenly, fully realize that you’re out in the jungle expressly for the purpose of offering yourself to a tiger, with the idea that this offering constitutes some sort of perverse analogue or corollary to your personal loss and guilt and perceived deficiencies as a man and husband and son, it’s easy to make the poem take a dark turn! That is, if you’re still alive to write it down. Advice to young poets #1: you have to be alive to write it down. Remember that. Don’t get eaten.

More seriously and directly to your topic, a reviewer recently commented that my poems tend to shift toward black comedy, so I find your echoing yet distinct read on this intriguing. Just about any good poem requires a turning, an opening, a moment when the piece’s true agenda or subject announces itself and perhaps surprises. In the particular case of my poems, I think I’d now like to be a little cagey and say I should think about this some more. I suggest also in your comment lies a clue, again, about how to link the personal, the deeply felt, with whatever exotic surrounding material, so that the two inform one another and resonate. Maybe. Good question, evasive answer.

Chapter 16: One of my favorite sections of the new book is “The Dead Metaphors,” in which each poem is a riff on an overused metaphor. There is a lot of verve in those poems, and you show how the most overused idea can become fresh with the right language. How did you get started on those poems? And do you have a favorite one?

Brewer: “Verve” means being a smart-ass, yes? That’s the section I mentioned earlier that seems different from the rest of the book, a bit of ribald humor and literary cynicism amid all this deep feeling. Even if Red Hen and I are trying rabidly these days to rebrand me as “sensitive,” there must be limits!

I’m glad you like those poems. Their genesis was simple: I was out in the yard one night with Jasper, sipping one of my fabled martinis and watching the sunlight limn a nice spider web. I thought, “Too bad you can’t write about spider webs anymore.” Then I had a little “aha” moment and spent a very enjoyable summer writing rude poems. Those are poems I was able to write at the house. If you notice, the series morphs from literary cliché to cliché of behavior and attitude. One that’s popular at readings is “Dead Metaphor: Learning the Bicycle.” I swear, one year when I was editing Poems & Plays everybody in America wrote a poem about teaching or learning how to ride a bicycle, and most were sent to me. So here I get to try to bake my cake and nosh it too, which of course is the challenge of all those poems: to acknowledge the tired conceit and then craft a decent poem from it.

Notice I said “try.” As I get older and ideas get thinner, I’ve turned a lot to series. You get up in the morning and have something specific to work on. I recently finished a sequence about a character named “Ghost,” a sort of purgatorial figure wandering the hills of Spain. They were fun to write. Does Ghost hunger? Does Ghost bleed? Can cats see him? Et cetera. What’s the rest of the world thinking about this morning? Make the coffee, sit down, get on with it.

Chapter 16: Finally, is there anything you would like a reader to know?

Brewer: Absolutely. Because readers clamored for it, my website is currently under construction. Check it out. Actually, no one clamored for it, not even my mom. But we’re doing it anyway because Red Hen made me do it, and we’re family.

To read a poem by Gaylord Brewer, click here.