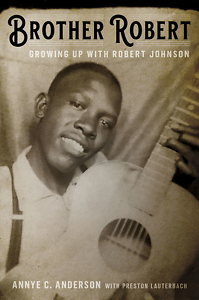

Remembering Robert Johnson

Brother Robert provides a human perspective on the man who changed American music

The city of Memphis plays a featured role in Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson, a memoir by Annye C. Anderson, the legendary musician’s younger stepsister. As Preston Lauterbach, Anderson’s co-author, writes in the book’s epilogue, “During Brother Robert’s time, people called Beale ‘the Main Street of Black America.’ Much more than a hangout for blues musicians, Beale had a storied history, a cast of colorful current characters, and a list of lively venues, from low-down dives to first-class theaters infusing the atmosphere around Johnson.”

This was the Memphis neighborhood where W.C. Handy created the blues at the turn of the 20th century. By the 1920s, it housed a pulsing, crowded blend of speakeasies and music halls, brothels and houses of worship, criminal elements and respectable families. As Anderson, who turned 94 this year, tells it, her mother Mollie Spencer was “a hardworking woman, a Christian woman,” who wouldn’t tolerate “any blues and finger poppin’ in her house.”

But nearby was the home of Anderson’s adult sister Carrie, where the young girl and the teenage Johnson could listen to popular music — on the radio, on the Victrola, and in live performances by relatives and neighbors. It was there, Anderson says, that her sister “helped to rear Brother Robert, and she bought him his first guitar.” He was soon playing at local house parties — not only the blues, but country music and other popular genres. Anderson lived with her stepbrother off and on for 11 years, starting when she was only three, but her recollections are sharp and detailed. She is perhaps the only living person who knew Robert Johnson.

As Lauterbach explains in his introduction:

The first memory of Robert Johnson in this book is of a long-legged eighteen-year-old carrying a toddler up a flight of stairs. The last is of him playing at a party celebrating Joe Louis’s victory over Max Schmeling. In between are memories of him taking a little girl to the movies, caring for her father’s horse, teaching her a simple piece on the piano, and sitting outside with his guitar, singing nursery rhymes for her and her friends or playing upbeat tunes that got them dancing.

The first memory of Robert Johnson in this book is of a long-legged eighteen-year-old carrying a toddler up a flight of stairs. The last is of him playing at a party celebrating Joe Louis’s victory over Max Schmeling. In between are memories of him taking a little girl to the movies, caring for her father’s horse, teaching her a simple piece on the piano, and sitting outside with his guitar, singing nursery rhymes for her and her friends or playing upbeat tunes that got them dancing.

The complicated branches of family that produced Anderson and Johnson trace to Mississippi, where Johnson was born, where popular legend has it that he sold his soul to the devil at “the crossroads,” and where he died mysteriously in 1938 at the age of 27. But his life as Anderson recalls it — like the roots of Johnson’s music — is very much a Memphis story. Lauterbach, a historian and author of Bluff City, Beale Street Dynasty, and The Chitlin’ Circuit, proves an ideal interviewer to tease this fascinating tale from the nonagenarian, first at her home in Boston and later on joint trips to her old Memphis haunts.

For that is what constitutes the bulk of this short book: an extended interview, a free-wheeling journey through old times with an earnest historian and a sharp-witted witness. Mrs. Anderson, as she insists Lauterbach call her, remains a child of the city that gave the world the blues and ultimately rock and roll. Although her life after Johnson’s death led her to the East Coast, college, and a long career as a teacher and school administrator, she brings her brother and the Memphis of her youth to life with verve and humor, in a dialect that could have originated nowhere else:

When I got to Sister Carrie’s with the barbecue, I saw my father cutting Brother Robert’s hair. All the pots were out, heating water on that stove. That’s how Brother Robert took a bath in a cold-water flat. Brother Robert kept himself clinically clean. … He was tall, slender, and built like the way women like men, especially black men, to be built. He had the African physique. He didn’t have overly broad shoulders, he was high-hipped, had narrow hips.

Until now, most people knew Johnson only through his recordings. Of those, Lauterbach reminds readers that “he only spent a few days making them, and what we are hearing is barely an hour and a half of his life.” And yet those songs influenced generations, including The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Eric Clapton. As is so often the case in American music history, Johnson was paid what Anderson called “peanuts” for his work, with decades of profits going to rich white men in distant cities. The latter part of the book is devoted to the often-infuriating ways that others tried to take advantage of the family to claim a piece of that legacy and the ways his sisters tried to reclaim it.

This book gives Mrs. Anderson at long last a chance to have her say — and what a stirring conversation it proves to be.

Michael Ray Taylor is author of Hidden Nature, a mixture of memoir and subterranean natural history to be published in August 2020. He chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas.