Singing What You Mean

Poet Robert Wrigley talks with Chapter 16 about the necessity of stories and music

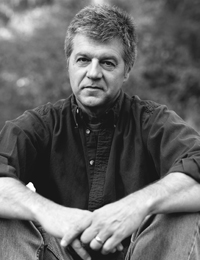

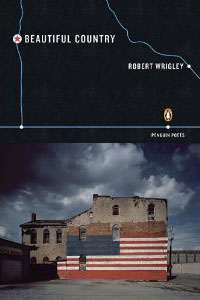

Robert Wrigley, the author of five collections, writes poems that speak to daily concerns about family, aging, and the land we inhabit. This is a poet who built his own writing studio from the foundation up, so it comes as no surprise that his poems are equally ambitious and well structured. Prior to his reading at Vanderbilt University on October 25, Wrigley answered questions via email about his life in Idaho and his goals for poetry. As he explains, “poetry exists for three central reasons: to delight, to instruct, and to wound. Some poems do one of those three things; some do two; some all three.” Wrigley’s own poetry certainly does all three—and with a grip akin to that of a novel and a lyricism akin to that of a song.

Chapter 16: The classroom prepares us with skill sets, but the tough questions about how to deal with identity, aging, life’s purpose, etc., have to be

learned elsewhere. Your poetry definitely offers insights into how to live and how to accept this life as it is, full of its quiet joys and great sorrows. Poems such as “Heart Attack,” “Thatcher Bitchboy,” and “News” are a just a few examples. For you, why is poetry a good place for meditating on those questions?

Robert Wrigley: I suppose I simply prefer to believe that poetry, like any other essential human activity, must have some purpose, even if it does not have one that’s especially useful (like any other living thing, poetry’s most essential purpose might well be keeping itself alive, perpetuating itself). But I have come to the sense that poetry exists for three central reasons: to delight, to instruct, and to wound. Some poems do one of those three things; some do two; some all three. And I also believe, in addition, that one of the best reasons for making poems is to undercut the notion that there are, let’s say, three reasons for writing poems. Poetry is a good place for comedy, tragedy, history, challenge, revolution—you name it.

Chapter 16: “Economics” from your third collection is a good example of the skillful manner in which you balance storytelling with lyricism: the details build suspense until the reader is almost cringing. We suspect what is going to happen, yet the poem still surprises and haunts. Do you consider yourself to be a storyteller?

Chapter 16: “Economics” from your third collection is a good example of the skillful manner in which you balance storytelling with lyricism: the details build suspense until the reader is almost cringing. We suspect what is going to happen, yet the poem still surprises and haunts. Do you consider yourself to be a storyteller?

Robert Wrigley: Sure. We’re all storytellers. We’re all stories. Stories are how we make sense of existence. But stories, like history (which is, of course, a story or stories), give the illusion of moving horizontally through time. But that’s not the way stories are actually made: they move vertically too. They are about their own telling, about she or he who tells them, and about the people and the place the story takes place in. There are people who think narrative in poetry is somehow “worn out,” but that’s silly. They have to make their case with story to make such an assertion.

Chapter 16: What are some of your poetic strategies to keep the lyricism of the poem from becoming buried under the story or anecdote that inspired the poem?

Robert Wrigley: For me, the poem’s vertical movement is usually connected to sound, to the music of the language. I like to push sound in order that the sound of the words (which is to say, the sound of the story) will in fact move the story in new and surprising directions. Keeping the need to report from swallowing the need to sing is what I’m talking about. Theodore Roethke said, “If you cannot mean, then at least sing.” I guess I say, “Sing what you mean.”

Chapter 16: “The Milking” is a great poem that tells about a man beating a cow that kicked him “for some good reason.” We know the cow will endure a beating when the man “grabbed a long-handled spade / and as it swung through the still barn air / it made a whoosh like a scythe….” And we also know, that despite witnesses, there’s no stopping this violence. A lot of your poems address violence, yet never in expected ways. Could you talk a bit about the way you define violence and how you see it functioning in poetry?

Robert Wrigley: Violence happens, though as Stephen Pinker’s wonderful book, The Better Angels of our Nature, suggests, we—and humanity at large—are actually getting less violent with each generation. It seems counter-intuitive, but it’s true, at least statistically. I was discharged from the Army on the grounds of conscientious objection; the last physical “fight” I had, I must have been nine or ten.

Robert Wrigley: Violence happens, though as Stephen Pinker’s wonderful book, The Better Angels of our Nature, suggests, we—and humanity at large—are actually getting less violent with each generation. It seems counter-intuitive, but it’s true, at least statistically. I was discharged from the Army on the grounds of conscientious objection; the last physical “fight” I had, I must have been nine or ten.

But I have lived most of my adult life in what most of the rest of Americans would see as “wild” places. We have four or five resident packs of coyotes in our neighborhood; we have bears and more recently wolves. The most common mammals around us are deer, which understand that they are prey and behave accordingly. I go for walks in the woods around my house almost every day, and I often see the results of a kind of acceptable, “natural” violence. Human violence always has a moral dimension, and there may be cases in which violence—human against human—is understandable, even necessary, and even cathartic. I’ve got a yet-to-be-completed and for perhaps a decade under-construction poem, spoken by one of the five men who executed Gary Gilmore in Utah. Capital punishment, by firing squad. Five marksmen with rifles all aiming as carefully as possible at a target above a man’s heart, one of their rifles loaded with a blank. Ever talked to someone on a firing squad? What would you ask him? It’s no different in poetry than it is in the culture at large. Violence. It’s awful and exhilarating; it’s horrible and righteous; it makes us not only who, but what, we are.

Chapter 16: Another distinguishing element of your poems is their emphasis on nature. As Christian Wiman said about your poems, they feel as if they are written by “a human who lives and feels his world and not, like too many poems, by a brain on a pedestal in some bare, unbelievably clean room.” Your poems leave readers with the sense that you like getting your hands dirty. What’s the reality?

Robert Wrigley: There are approximately 1.2 million people in Idaho; it’s a big state, and most of the people live within 80 miles of Boise (300 miles from me). Much of the central part of Idaho is comprised of two gigantic wilderness areas (both of which are larger than Yellowstone Park, but without the highways, hotels, and concessions). I live amidst a whole lot of nature, in other words, and it was the abundance of that kind of wild country that drew me to the northern Rockies and which has kept me here. I’ve had offers to go elsewhere, and so far nothing’s drawn me away. You either like that kind of natural world or you don’t. I do.

I like physical labor too. If there’s one problem with teaching, it’s that there’s so little actual heavy lifting. I have a writing studio I built myself, all of it. Excavation, foundation, framing, wiring, finishing, every part of it. I’d never built a building before, but I studied books, I kept my eyes open, and I learned. I like confronting problems and solving them, and since every poem is the creation of, and the solving of, a problem, it’s good practice. I like to sweat, too. I especially like poems that are of the body as much or more than those that are of the mind, or of the mind only. Our minds are our best parts—our handsomest, sexiest parts, even—but without the body, the mind doesn’t have much to do. I like doing, then writing about doing.

Chapter 16: In “52 Statements About Poetry,” Marvin Bell writes that “prose is prose because of what it includes; poetry is poetry because of what it leaves out.” What do you tell your own writing students about what to leave in and what to leave out?

Robert Wrigley: Well, I think poetry is poetry because of what it includes and what it leaves out. For me, it’s not about what’s in or out of the piece of writing that identifies it as poetry. There is nothing poetry can do that prose cannot also do. Nothing. The difference—the only difference between poetry and prose that matters—is that poetry is written in lines.

And since lines are poetry’s only unique characteristic, then they must be paid supreme attention to. And the line is utterly clear: there it is on the page, absolutely beginning and ending. And at the same time, codifying what a line ought to be is like codifying what love ought to be. Ten syllables? Five stresses? Worked for Shakespeare, Pope, Dryden, and innumerable others. Eight syllables, six syllables; four stresses, three; worked for Emily Dickinson. What about Whitman? What about Kay Ryan? We will never get to the end of possibilities with the line, because we will never get to the end of possibilities of syntax. (This is what keeps prose alive and vital.)

So, getting back to the question, I do talk to students about what to leave out or put in, but the really hard part of writing is knowing what’s enough. Too much information is as deadly to the poem as too little (no, too much is probably deadlier), but I spend most of my time finding ways to get students to work out the problem of leaving stuff out or in as a problem of craft—which is to say, of the line, of music, of diction, of figuration, form, and structure. The poem is a little machine; its parts move. It needs to work, even if the only thing it does is to bounce up and down, saying me!, me!, me!

Chapter 16: What advice would you give someone coming to your poems for the first time? Have you ever formulated the kind of introduction to your own intentions that Wordsworth gives in the preface to Lyrical Ballads?

Robert Wrigley: I don’t think I’ve ever done such a thing or even thought about it. I wouldn’t enjoy it much. It’s strange. If you have to explain to people what you’re doing, then are you doing it well enough? But there’s also this: the vast majority of your readers will not see (or get, or make sense of) half of what you’re up to, if you’ve done your job well enough. Read Shakespeare’s sonnet 43. Read it again the next day, and you’ll see something you did not the first time. Wait a week and read it again. Again, there’ll be more.

That’s the way real poems [work]—poems that aspire to the condition of literature; poems that accept and embrace complexity, both in terms of the literary product and in terms of the human experience. So, to a new reader, I can only say: welcome. I’ve done my best. I hope you find something here that delights you, instructs you, and wounds you. And may you, at some point, feel all three responses at once.

Robert Wrigley will give a free public reading on October 25 at 7 p.m. in Buttrick Hall room 101 at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Click here for event details.