Sophisticated Tales, Hardscrabble Lives

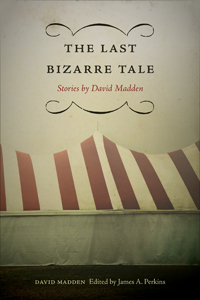

The stories in David Madden’s The Last Bizarre Tale reveal hidden hopes in the South’s dark corners

The Last Bizarre Tale, a new collection by Knoxville native David Madden, serves the dual purpose of introducing its prolific author to new readers and offering a summa to his long, impressive career. Sixty years of sustained productivity merits our respect, and the fact that so many of the tales carry the unmistakable sheen of a well-made story provokes admiration. The book demonstrates the protean nature of Madden’s gifts: his tales run the gamut of literary styles and genres, each entry marked with the stamp of its author’s ingenuity.

The Last Bizarre Tale evinces a mastery of the writing craft, a confident virtuosity that should be expected from a writing teacher (Madden is Robert Penn Warren Professor of Creative Writing Emeritus at L.S.U) and author of handbooks with titles like Revising Fiction. He evokes setting with subtle details integrated seamlessly into stories. In “A Human Interest Death,” for example, a man looks out the window of his home in East Tennessee, where many of the stories take place, and watches the red beacon atop a nearby ridge, “erected to warn planes not to fly too low.” The red light “seemed a personal sign of everlastingness, a reminder that his heart beat red and wet in the dark cave of his chest, but, also, of his dreary, day by day existence.” Over the course of the story, a biography in miniature of a humble accountant, that warning beacon enters twice more, each time altering the course of the protagonist’s life.

The Last Bizarre Tale evinces a mastery of the writing craft, a confident virtuosity that should be expected from a writing teacher (Madden is Robert Penn Warren Professor of Creative Writing Emeritus at L.S.U) and author of handbooks with titles like Revising Fiction. He evokes setting with subtle details integrated seamlessly into stories. In “A Human Interest Death,” for example, a man looks out the window of his home in East Tennessee, where many of the stories take place, and watches the red beacon atop a nearby ridge, “erected to warn planes not to fly too low.” The red light “seemed a personal sign of everlastingness, a reminder that his heart beat red and wet in the dark cave of his chest, but, also, of his dreary, day by day existence.” Over the course of the story, a biography in miniature of a humble accountant, that warning beacon enters twice more, each time altering the course of the protagonist’s life.

Madden uses stage props with similar efficiency in “Hurry Up It’s Time,” the collection’s most chilling tale. Greta and Dorish, two orphans living in an Upper West Side Manhattan orphanage become engrossed in watching the drama of a young couple living across the street. Madden skillfully entwines the orphans’ fates twenty years later with the sad events they had watched in dumb show as children. That story, with its Poe-like twist and O’Henry plot, characterizes Madden’s gifts for evocation and economy.

Madden uses stage props with similar efficiency in “Hurry Up It’s Time,” the collection’s most chilling tale. Greta and Dorish, two orphans living in an Upper West Side Manhattan orphanage become engrossed in watching the drama of a young couple living across the street. Madden skillfully entwines the orphans’ fates twenty years later with the sad events they had watched in dumb show as children. That story, with its Poe-like twist and O’Henry plot, characterizes Madden’s gifts for evocation and economy.

As accomplished as these stories are, however, Madden never flexes his literary muscle gratuitously or show-boats with fine writing for its own sake. The pieces here convey profound messages about heartache and loss, the consolations of beauty, and the struggle for dignity. Madden understands that life’s biggest mysteries involve questions of motivation and that, much of the time, there is no final answer. Who can explain why we do the things we do? In “Lights,” an actress’s son, who doubles as the stage technician for a small town’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire, misses lighting and sound cues and ruins his mother’s long-awaited first night as Blanche DuBois. He dreads his mother’s asking him why he “punished” her right at the moment when her career reached its zenith. “He still didn’t know why,” the son thinks. “He expected that one day, he would.” Or perhaps he won’t; either way, Madden’s story functions as a complex meditation on the expression of love and the path toward redemption.

In the book’s introduction, James A. Perkins (a one-time student of Madden’s) makes it clear that, for all the time Madden has spent in academia, he still prefers to write about “late-night, back-alley, marginal, maimed, hardscrabble characters.” The first story, “A Piece of the Sky,” confirms this penchant, chronicling a chance hook-up at a bus stop that leads to an erotic interlude aboard a borrowed house boat. Whether his heroes are professors hiding from mortality or youngsters seeking adventure, Madden captures the reader’s attention, using an impressive array of skills developed during a lifetime devoted to the art of writing.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford University as an undergraduate. He later returned to Austin, where he earned a Ph.D. in modern fiction from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.