“Sound Advice”

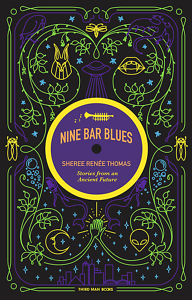

Book Excerpt: Nine Bar Blues

Faded vintage posters plastered the walls. Burgundy velvet covered the steps. Mopti walked up each one, careful not to brush against anything. Flyers and event postcards dangled along the sides, stroked him like fingers as he passed. Mopti shuddered.

Now he knew why he had the devil of a time finding the place. Must be a law against putting addresses on the buildings, Mopti thought. He passed the near-invisible Sound Advice sign many times on his own before Brenda had pointed and he finally saw “Vital Vinyl” in tiny letters beneath it. The run-down building was designed as if it was meant to fold up and disappear, accordion-style. Steep stairs led up to a blackhole door.

Now he knew why he had the devil of a time finding the place. Must be a law against putting addresses on the buildings, Mopti thought. He passed the near-invisible Sound Advice sign many times on his own before Brenda had pointed and he finally saw “Vital Vinyl” in tiny letters beneath it. The run-down building was designed as if it was meant to fold up and disappear, accordion-style. Steep stairs led up to a blackhole door.

When Mopti finished huffing and puffing, he looked around. Records filled the space, stacked in rows of teal blue wooden shelves and orange plastic crates, spilled across wide tables. Vintage toys, stuffed animals, old 45s and 78s, and Christmas lights hung from the ceiling. Album covers and occult signs and symbols decked the walls. Mopti saw at least three different kinds of Ouija boards. No one was in sight.

“So what are you looking for?”

Mopti nearly jumped out of his skin. The voice was right behind him. A thin older man wearing a “Don’t Hate the Player” shirt stood, hand on his hip, waiting. Castle Grayskull hovered over his head. He didn’t look like an occultist, just a hoarder.

“Something rare —” Mopti managed to say.

“Rare? Listen, you ain’t seen rare ‘til you’ve seen my X-ray collection. Straight from the Cold War.” His mouth approximated a smile. “Now we thought we had bootleggers. You got to see what they made over in Russia. I mean bone music.”

He waved and didn’t wait to see if Mopti followed him.

“They had to do everything in secret. Most of the good music was banned. See this?” He held it out so Mopti could note the illuminated ribcage. “They’d etch a copy right on an X-ray they stole from the hospitals, cut a circle with some kitchen scissors, and burn a hole right in the middle with a cigarette. Could play that sucker on anything, just as good as you please. Don’t tell me what people can’t do when they’re pressed.”

“I see,” Mopti said, scanning the room.

“Okey dokey,” Old Player said and placed the album back in its protective sleeve. “Bone music don’t float your boat, so what is it?”

Mopti paused, sorting what he should say from what he wanted to say. The store looked as if a truckload of albums had exploded inside. Vinyl was everywhere he looked. Not a single CD in sight.

Old Player shrugged. “If you’re into vinyl, you’re into vinyl. It’s not something you can explain. It’s just in you.”

“I don’t think much of it’s in me,” Mopti said, “but my uncle, he definitely was … a collector.”

“And what did he collect?” Old Player asked.

Mopti tried to answer. The house on Shands Bottom Road had piles of albums stored throughout every room, even the bathroom. Most, from what Mopti could tell, were blues, some jazz, but the collection spanned music from around the world.

Mopti tried to answer. The house on Shands Bottom Road had piles of albums stored throughout every room, even the bathroom. Most, from what Mopti could tell, were blues, some jazz, but the collection spanned music from around the world.

“A single record, pressed by unknown hands, never widely released. Something called The Great Going Song? I think that’s the name of it.”

Old Player frowned. “Well good luck with that.”

“What do you mean?”

“Haven’t heard that name in a long time. Most folks hunting for that good and crazy.”

Mopti raised a brow. “Well, I try to be good. Not sure if I’m crazy yet …”

The shop owner laughed. “No disrespect, son, I’m just saying. Don’t know if they start off that way, but seem like by the time they come through, they’ve lost it.” Old Player squinted at him. “The last somebody call hisself looking for The Great Going Song looked a bit like you. Old Oumar. Y’all related?”

Mopti nodded and lowered his eyes. Shame made his cheeks feel hot and flushed.

Old Player turned around and picked up one of the faced out albums. “Listen, you want some psychedelic acid jazz? Might as well listen to some of this.” He handed the album to Mopti. “This is a rare one.” He leaned his elbows on the counter as he moved the needle. Suddenly the air erupted into the sound of blue crystals. Mopti felt as if he’d been rained on. “What’s your name?”

“Mopti Cissé.”

“I’m sorry for your loss. Your uncle was a nice man. A little strange,” Old Player said, “a bit obsessed, like most vinyl hounds, but ain’t no sense in chasing after fairy tales.” He stared at Mopti. “Especially tales that can get you killed.”

If the tick-ticking of the overhead fan had been a record player, the needle would have skipped and scratched. Mopti’s eyes and lips formed a series of questions.

“All I’m saying is that folks been looking for that album a good, long time. Nobody’s found it yet, but a whole lot of folks found some shit they wished they hadn’t.”

“Like what?” Mopti shivered.

Old Player shrugged. “Bad luck. Misfortune. Death. The usual stuff. Which is kinda funny, since the whole point of The Great Going Song is to overcome death in the first place.”

Mopti picked through a box of 45s on the counter. A James Brown bobblehead nodded at him.

“I’ve been trying to understand why my uncle wanted the album so much. It looks like he spent a considerable amount of time and resources trying to track it down. And there isn’t a lot about it out there.”

Old Player looked thoughtful, rested his arms on the cluttered counter.

“Some hobbies have a way of taking over you. Collecting can be like that, like a drug. You never know if and when you’ll grow addicted. Sometimes it’s hard to figure out when you should stop — if you can stop.” He stared at Mopti, his eyes like pennies. “But The Great Going Song is different. It’s not your ordinary record.”

Mopti didn’t like how he was looking at him. He turned and dug through a crate, flipped through familiar names and images. He paused at one, Otha Turner and the Afrossippi Allstars. “My uncle has a lot of these artists. Some he has multiple copies of. Is that Going Song album really valuable?”

A pinwheel spun over Old Player’s shoulder. His eyes took on a waxy sheen.

“Why? You looking to get into collecting?”

“No. I was just curious.” Mopti slid the Allstars back into the crate. “My uncle wrote a lot about different albums. This one seemed to stand out for him. But I can’t figure out who the artist is.”

“Nobody knows. Part of the mystery. And yeah, rare vinyl can get up to crazy amounts. I know a previously unknown blues 45, from Sun, that went for $10,000. A 78 went for $30,000. That was online and the collector didn’t even blink ‘cuz that was a steal. But the record you’re talking about is super rare, more rare than hen’s teeth. Only three copies were made.”

“Just three?”

“Yep. They say the album is made of the perfect sound, full of all the colors of our world. It’s a miraculous key, said to open doors that only a god can.”

“A god?” Mopti didn’t like this kind of talk, and the more the man spoke, the more he sounded like Uncle Oumar’s strange, manic notes.

“Only one number in our universal spectrum is the same color and sound, the core frequency of creation, nature, life. The original musical scale has only six notes, but they say that there are actually nine.”

“Nine? Now you’re speaking my language,” Mopti said. “I’m an accountant. I speak numbers fluently.”

“Ah,” Old Player said. “But these are the kind of numbers that can change a world, a kind of sacred geometry.”

“I’m familiar with this in my country,” Mopti said. “It is a science of creating space, yes? Art, what have you, that reflects faith. You build architecture, music, writings that exhalt the Greatness, the Oneness …”

Old Player’s eyes sparkled, his mouth settling into a tight grin. “You are your uncle’s nephew.”

“Did he come here often?” Mopti asked, unsure if he should be pleased or offended.

“At first. He would buy me out of my blues and some of the rarer, off the beaten path jazz. Place special orders every now and then. He had an eclectic taste. Started off with Hip Hop, classics, and fresher takes. Iron Mic Coalition, Nicole Mitchell’s Black Earth Ensemble, Kamasi Washington, Ekpe Abioto and the African Jazz Ensemble, big pure, free sound like that. But I didn’t see him much before,” he paused. “Before he died.”

“Yes. I am not as versed on this as he was,” Mopti said. “He certainly had a love of music that must have comforted him. I don’t understand it but somehow it drove him. My family had not seen him for many years. I, myself, have no memories of my uncle, though I am told we do share a likeness.”

Old Player didn’t look convinced.

“But I don’t share his music hobby, the collecting as you call it. What is it about this Going Great music? If there were six notes in the original music scale, how do you get nine?”

“It’s called The Great. Going. Song,” Old Player said, emphasizing each word to reveal tiny, sharp teeth. To Mopti he looked irritated. “It is made up of the original six, solfeggio.” He sang the notes, apologizing. “Forgive me. I’m no Maria von Trapp but you get the idea.”

Mopti nodded. “I … I think so.”

“Okay, well, you start with the original six that these old Benedictine monks created to sing their Gregorian chants but it’s older than that, dates back to biblical days,” he said. He took a sharpie from a red “Tighten It Up” cup and started drawing. “396, 417, 528, 639, 741, and 852,” he said. “Plus three additional notes, 963, 174, 285. Together they form a perfect circle of sound, and that circle of sound can heal all things, make what is dark, light, what is broken whole. The nine sacred notes of healing. The basis for a song that can heal this broken planet.”

Copyright (c) 2020 by Sheree Renée Thomas. Reprinted with permission of Third Man Books. All rights reserved. Sheree Renée Thomas is an award-winning short story writer, poet, and editor. She edited the Dark Matter speculative fiction anthologies, which won two World Fantasy Awards. Her previous books include Sleeping Under the Tree of Life and Shotgun Lullabies. Nine Bar Blues: Stories from an Ancient Future is her first fiction collection. She lives in her hometown, Memphis.