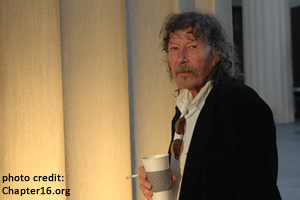

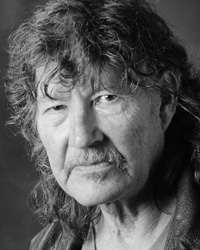

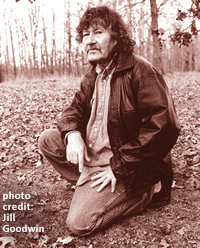

Starring Gary Cooper

In a story discovered after his death, William Gay tells the tale of a good-hearted drifter who finds an unlikely landing place at the drive-in

He rose and trudged wearily onward. In the west the sun had gone and the last vestiges flared in chromatic red and orange and windrows of lavender clouds dulled to smoke gray. Somewhere westward night was already facing and he went on toward it as if he and the darkness had some appointment to keep. For some time he’d been aware of sounds, the equable cries of birds, a truck somewhere laboring through the gears.

Yates woke with light the color of haze heavy on his eyelids, heat bearing down on the flesh of his face and throat. His throat felt as if it had been cut with a rusty pocketknife and he had a thought to feel and see but some old caution stayed his hand. Some things are better not known. He judged it better to enter into the day with caution, who knows what lay ahead.

Or behind. He lay very still and tried to locate himself. Where he was, where he’d been. Jagged images of the night before came unsequenced and painful, little dayglo snippets of chaos. Like snapshots brought back from a backroads vacation of dementia. He’d been in a car, six or seven men sitting tightly crammed shoulder to shoulder. Had there been a woman? He seemed to remember perfume, soft drunken laughter. A siren, the systole and diastole of a cruiser’s lights. Riding through the arcane woods down to a hollow, brush whipping the car, the breathless impact of a tree trunk. The protest of warped metal and a final shard of glass falling like an afterthought.

Or behind. He lay very still and tried to locate himself. Where he was, where he’d been. Jagged images of the night before came unsequenced and painful, little dayglo snippets of chaos. Like snapshots brought back from a backroads vacation of dementia. He’d been in a car, six or seven men sitting tightly crammed shoulder to shoulder. Had there been a woman? He seemed to remember perfume, soft drunken laughter. A siren, the systole and diastole of a cruiser’s lights. Riding through the arcane woods down to a hollow, brush whipping the car, the breathless impact of a tree trunk. The protest of warped metal and a final shard of glass falling like an afterthought.

Running through the woods. One picture of him frozen in air limbs all outflung and his mouth an O of surprise and an outstretched vine or bramble or perhaps clothesline hooking him beneath the chin and his terrific momentum slinging him into the air. Later on, the cry of some beast he suspected was yet unrecognized by science, some horrible hybrid of loon and mountain cat. Oh Lord, he said aloud, then immediately wondered if there’d been anyone about to hear it and opened his eyes to see.

The first thing he saw was the sun and he wrenched his face away in agony and saw a field of grass, a horizon of stems and seeds and clover blossoms like trees in a miniature. A sky of a bluegreen that seemed to be alive, so did it pulse and throb. He looked back into the ball of white pain that stood at midmorning.

An enormous blue monolith seemed to rise above him, and it took him a few moments to realize that it was his left leg distended into the air, rising at a precipitous angle and tending out of sight into a malefic sky he wanted no part of. As if some celestial beast or outlaw aberrant angel had snatched him up by the left leg to hove him off, found him ungainly or not worth having and departed or simply paused to rest.

Well now, Yates said tentatively.

When he rose he noticed the white flaps of his pockets turned wrong side out and when he patted himself down found he had scores no more than the nothing whatever he’d come into the world with.

After a time he realized that the cuff of his jeans was caught on the top of the chainlink fence and hung him here in dismissal. Well son of a bitch he thought. Reckon I was chasin something or runnin from it. He remembered voices and gunfire and riders and their steeds that seemed to have been lithographed on the stormtossed heavens themselves. By inching forward he was able to jiggle his leg. He looked as if he was climbing the fence with his buttocks , using them as a snake uses his ribs. In this manner he was able to accumulate enough slack in the denim to wrench his leg free. He rolled backward and sat up in the grass with his legs folded under him and his face in his hands.

Oh Lord, he said. A person ought not have to live like this.

He looked about cautiously, like a player sweating in the last down card in a poker game. Who knew what he’d find. A dead body, a canvas bag of money stenciled First National Bank, a knife with blood crusted on its blade, a dead sheriff with a bloody and unserved warrant clutched in his fist. But there was just the fierce arsenical green of the field he was in, a distant treeline, birds moving above it like random or malignant spores on a glass slide. When he rose he noticed the white flaps of his pockets turned wrong side out and when he patted himself down found he had scores no more than the nothing whatever he’d come into the world with. Just these ragged vestments of jeans and tee shirt. A right shoe. But Yates was of a philosophical turn of mind and this served him in good stead here. If you don’t know what you had you can’t miss it when it’s gone.

He judged the road southward for he’d seen the sun glare off the tops of occasional cars and as this was the only sign of civilization he’d seen he followed the chainlink fence toward it through the stunned hot silence of the day. He was enormously thirsty and all he could think of was water.

When the fence ended by the roadbed momentary indecision halted him. He looked left, he looked right. Right was touched by some vague familiarity ephemeral as social memory and never one for covering the same ground twice he turned left and plodded along the shoulder of the road head down as if he were looking for something he’d lost among the brackery of dewberry vines and honeysuckle.

When the fence ended by the roadbed momentary indecision halted him. He looked left, he looked right. Right was touched by some vague familiarity ephemeral as social memory and never one for covering the same ground twice he turned left and plodded along the shoulder of the road head down as if he were looking for something he’d lost among the brackery of dewberry vines and honeysuckle.

Each footfall brought a shock of electricity to his brain. As if his feet completed some bygone telluric circuit when they touched the earth. He thought of white rats, other small laboratory animals whose job it was to close the electrical circuit painfully until they learned better. He began to feel watched by some celestial scientists that studied him from on high, watched one step after another. This is an exceedingly slow subject, why doesn’t he learn? But Yates was of an optimistic nature and after he began to sweat he felt better and he thought if he could find some water he might actually live.

He saw the sign long before he could read the letters and beyond it the screen of a drive-in theatre and the green of earth shaped in curved tiers where the rowed speaker posts stood like some esoteric crops. Centered in the back of the convoluted earth a white stucco building warped itself up out of the sundazed landscape. Past that a white frame house set in the blue shade of the hills.

A figure he judged female was moving purposefully along a row of speakers at some obscene chore, bending and straightening, stooping and rising up the rows going on like someone picking cotton. After a time she turned past the white building toward the house in the woods and vanished in the trees.

He could read the sign now. FREE CAR THURSDAY, it said. He stopped and studied it bemusedly perhaps looking for amendments, fine print. There was none. He wondered what day it was. He spat a cottony mass onto the roadbed. Probably a catch to it, he said aloud. He went on.

He was soon upon the car itself. It was sitting aloft parked on a platform framed atop creosoted poles. A ramp of sawmill lumber led from the earth up to the platform. Yates crossed and peered through the fence. A faded green Studebaker that looked as if it had been ridden hard and illy used. But free was free and a gift mouth not to be examined. It had presumably been driven up the steep ramp.

I been broke all my life and ain’t robbed no bank yet.

He left the roadbed. He turned in where a narrow cherted drive branched off past a sign that said Star Vue Drive-In and crossed between the screen where it rose enormous on tall posts and an untenanted ticket booth and followed the curving drive to the stucco building.

He walked all around the building. He was looking for a spigot but he didn’t find one. He felt dry as gunpowder, weightless as dry leaves. The cold black water of his underground lake ached like ice in his throat.

He pushed open a door hinged to open either way like the batwing doors of a saloon. Hey in there, he called. No answer. Just the hum of machinery, the whir of an unseen fan blowing. Looking about he saw that he was in the concession stand, a cornucopia of boxed candy bars and gum, bagged potato chips, and the first thing he saw was the soda fountain with its gleaming chrome appurtenances. Its cunning pump levers with knoblike gearshifts. Compartmented paper cups you pulled free one by one, a sliding door under the counter that revealed miniature ice cubes in a stainless steel bin.

He’d learned how to work the dispenser and he’d finished a Coca Cola and half an Orange Crush when the door opened and a redhaired woman stepped through it. She was looking back over her shoulder and didn’t see Yates until she’d slammed into him. Shit, she said, and leapt away wildeyed, orange soda all down her front.

He’d learned how to work the dispenser and he’d finished a Coca Cola and half an Orange Crush when the door opened and a redhaired woman stepped through it. She was looking back over her shoulder and didn’t see Yates until she’d slammed into him. Shit, she said, and leapt away wildeyed, orange soda all down her front.

What are you doing in here? Who are you?

Yates was picking up ice cubes and replaced them in the paper cup. He looked about for something to mop up the soda.

I just come in off the road. I was needin a drink of water.

I guess if you was broke you’d just walk in a bank and help yourself, she said. Just fill up your pockets and be gone.

I been broke all my life and ain’t robbed no bank yet.

Well, you’re young, she said. Give yourself time. No need in rushing into things.

Yates set the ice on the counter and studied her. She had bright green eyes and pale skin faintly freckled. A medusalike head of red curls sprayed so heavily in place they seemed to have been glazed and fired in a kiln. He judged her somewhere in her forties, maybe fortyfive. She was dressed so heavily for the weather in warm men’s clothing and he could tell nothing about her body.

Well? Do you want to see my teeth?

What?

You’re looking me over like a horse at a auction barn.

Yates looked away and said nothing.

You just pushed the door open and walked in like you owned the place. We’re closed here. You can’t show movies in the daytime.

I was just lookin for a faucet and couldn’t find one. I’ll get a drink and be on my way.

On your way to where?

I don’t know. Whatever’s down that road.

Where’d you come from?

He gave a onearmed gesture so meaningless it seemed to encompass the horizon, the world itself, Nowhere at all.

Haven’t you got folks?

Yates finished off the orange drink and crunched the ice cubes in his teeth. He’d never seen ice cubes that cunning and small. As if they’d been served only halfgrown. He’d always been perplexed by the origin of things and he wondered how they were formed.

Everybody’s got folks or I wouldn’t be here, he said. But mine are all dead. I’m an orphan. I fell in with a bad bunch and got robbed. It is a rough bunch on the road these days. What about that car?

What about it?

Is it free like the sign says?

We hold a drawing on Thursday night. A raffle. All week long the tickets are put into a box and one is drawn out. If the person who bought that ticket is here he wins the car.

It still seems fixed to me. You got to already have a car to win this car.

No. We get a lot of walkers. It’s hard times. Lots of folks don’t have a car.

Oh. Then it ain’t really free.

What?

If you have to buy a ticket and come to the show.

The car is free. You buy the ticket to see the movie and speaking of free, the drinks are not. They’re fifteen cents apiece.

Like I told you I was robbed. They turned my pockets wrong side out. I reckon I owe you fifteen cents. He wadded the cup, wondering if there was some kind of chemical test she could subject the cup to and detect residue of Coca Cola amidst the orange, a lie detector test. You got something I could do to work it off?

I’d not charge a thirsty man for a cold drink. Even one who helped himself without asking. But there’s work here if you want to make a few dollars.

Yates had given up on the Studebaker. No free car today.

He went dragging an enormous aluminum garbage can into the rowed speakers and stopped to survey the grounds. They were strewn with popcorn bags and coke cups and cigarette packs and napkins. Windtossed paper that looked like debris from some huge storm. Every son of a bitch that passed in the night must of just raked out his car and drove off, he said.

But it was light easy work and he went at it with a good heart down the tiers picking up scrap bothhanded like a man picking cotton. Sweat soaked his shirt as he worked, but it was good to be in a day that seemed guided by purpose. He began to whistle some old lost song from his childhood. He’d police an area around the can then he’d move the garbage can and commence again. When the can was full, he dumped it into a steel incinerator behind the concession stand and set it afire and went back to the field. Once when he was dumping the can into the mesh cylinder she came out to check on him. Well, she told him, you will work. I’ll say that for you.

On the last tier next to the woods the findings were of a different nature. Beer cans, a few half pint bottles. A thin tube of latex like a sea fluke left by the recession of a briny tide. Eros’ calling card. God semenstained container love had come in. I ain’t touchin that, he said aloud. He hunkered on the earth to think about it. He didn’t know what the protocol was here. He wondered what she did in this situation. Should he go ask her. How to phrase it. He couldn’t think of a delicate way to put it, and perhaps it had never happened before. As so often it was of no moment. At length, he rose and caught it up on a length of a stick and carried it out to the garbage can, holding his arm stiffly extended and slightly to the side as if germs were blowing off it.

When the last of papers were burned he sat for a time behind the concession stand in the shaded silence and just listened to the day. Every sound seemed separate and distinct, a thing to itself, and each seemed to possess significance beyond themselves, as if each sound stood for something. A truck passed on some distant unseen road. Doves called from the woods beyond the house, soft and sad as if they had some loss to mourn to him about. He looked up. The sky was cloudless and blue and bottomless and within it birds shifted and spun in the wind’s keep like small dark kites that had come untethered. He rose to go inside and tell her he was finished. For the first time in weeks he felt at peace with himself.

When the last of papers were burned he sat for a time behind the concession stand in the shaded silence and just listened to the day. Every sound seemed separate and distinct, a thing to itself, and each seemed to possess significance beyond themselves, as if each sound stood for something. A truck passed on some distant unseen road. Doves called from the woods beyond the house, soft and sad as if they had some loss to mourn to him about. He looked up. The sky was cloudless and blue and bottomless and within it birds shifted and spun in the wind’s keep like small dark kites that had come untethered. He rose to go inside and tell her he was finished. For the first time in weeks he felt at peace with himself.

From his dark booth the projectionist showed a Gary Cooper western of one man backed to the wall and ultimately making his stand. To Yates the projectionist tending his whirring machines was an alchemist laboring over his potions. As if he’d concocted this parable, decoded it from some collective unconscious. Never had Yates seen rugged individualism so rewarded, yet so neatly thwarted. He watched as the projectionist switched between the reels, learned to watch for the white circle in the upper right hand corner of the frame that signaled the end of the reel: ever after he would imagine this appearing to him like a sign of a celestial guidance and he would know that whatever particular reel he was in was ending, and he would think, got to go, time to fold these cards, time to walk off down the road. Start another show.

Long after the lights had come on and the last car gone he was still transfixed by the play he’d seen. As if in some manner he’d acquired a friend in Gary Cooper, some stoic black and white familiar who’d stand beside him when the going got tough.

How’d you like that part where his wife finally shoots that last outlaw? he asked.

I’ve seen it too many times, the woman said. I always know what’s coming. I don’t ever like movies anymore. The bad guy always gets shot, the good guy always gets the girl. It never shows what happens after that.

Her name was Willodene Roth and he’d learned she was from Michigan.

How’d you wind up way down here, he asked.

My husband was looking for the ideal spot to drink himself to death, she said. He figured this was the perfect place. As it turned out, he was right.

She was cleaning the grill, Yates was sweeping up cigarette butts and trampled coke cups.

I don’t see how you’ve managed to run this place, he said. Sellin tickets and all. Cookin all night these hamburgers and all. It’s run us both to death.

I had a helper until a few nights ago, she said. She was at emptying the cash register, stowing the money in a white canvas bag.

Why’d he quit.

He didn’t quit. I fired him.

How come. Looks like you’d need the help.

I didn’t need that kind of help, she said. He knew I was a widow and he thought that gave him a license to take advantage.

Mmmm, Yates said. At the back of his mind he’d been idly wondering where he was going to sleep tonight and guessed this told him where he wasn’t.

He wound up sleeping on a sort of chaise lounge in the concession stand. From the house she brought blankets, a pillow. There’s a shower back there in the bathroom, she told him. I don’t want to get personal but I believe you could stand one. I guess hygiene is different on the road.

When she’d gone he examined the place at his leisure. There was a back room with a freezer. He opened it, cold air smoked out. Bags of frozen hamburgers, neat bundles of wieners corded in their plastic sarcophagus. He’d never seen such largesse. In the other room tiers of cartoned candy bars, each identical in the cellophane wrapper. So accessible, all you had to do was tear off the paper. The coke machine was inexhaustible as the lemonade spring told of in some old song.

He ate three leftover hot dogs and a bag of potato chips and then he ate a candy bar and drank a cherry coke. He looked about. Well now, he said. He was enormously content, master of his domain, lord of all he surveyed. He’d been idly thinking about lovestarved widows and lonely mile scarred drifters but this no longer seemed applicable here. At length he made his bed, crawled into it and pulled up the covers. He lay for a time, marveling at the switchbacks and reversals life can take, the odd trips it can take you on. This very morning he’d awakened lost and penniless, even the next meal a dim prospect. Now he was sated and content, semiproprietor of a prosperous business. For a while he lay as he tried to concoct a plan to jerryrig the drawing for the car. An accomplice perhaps, raising aloft the ticket Yates had slipped him. That’s me, the accomplice cried, that’s my number.

But the day had been too full and he was enormously weary. The icemaker made a comforting drone. His eyes closed. When he opened them halfdozing he imagined his head was resting on the bone of a saddle, the ceiling sprent with stars, and that from the dying campfire, Coop watched him with bemused and tolerant eyes.

Copyright (c) 2013 by the estate of William Gay. All rights reserved. This story was discovered among Gay’s papers in manuscript form and is faithfully reproduced here without significant editing. To read Chapter 16’s tribute to William Gay, including essays by Darnell Arnoult, Adrian Blevins, Sonny Brewer, Tony Earley, Robert Hicks, Derrick Hill, Suzanne Kingsbury, Randy Mackin, Inman Majors, Corey Mesler, Clay Risen, George Singleton, Brad Watson, and Steve Yarbrough, please click here, and follow the links to an interview with Gay and two excerpts from the novel he was writing at his death.