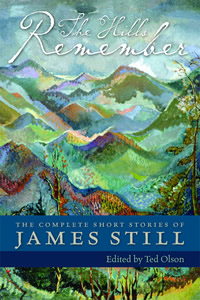

Steady as Time

In The Hills Remember, Johnson City poet Ted Olson collects James Still’s beautiful stories of Appalachian life

Appalachian poet, novelist, and short-story writer James Still was born in Alabama and educated in Tennessee—at Lincoln Memorial University and Vanderbilt—but he spent most of his life in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky. Trouble finding work during the Depression drew him to Knott County, Kentucky, but it was the wild beauty of the place that kept him there. As he got to know the fiercely independent inhabitants of a harsh landscape, he began to write about their lives. In The Hills Remember, editor Ted Olson, professor of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, has put together a complete collection of Still’s short pieces. Spanning more than forty years, they represent a link between Still’s poetry and his novels. As Olson explains, “His short stories expanded upon the strengths of his poems and ultimately encouraged his imagination to explore the extended narrative novel form.”

According to Olson, “Still distilled his visions and his values into minimalist landscapes. Indeed, to many readers his short stories seem closer to outpourings from the oral tradition than to conventional, self-consciously composed ‘literary works.’ They stand out as evocative and timeless yet remarkably simple tales and legends from the soul of Appalachia.” Nevertheless, Still did not consider himself a regional writer: in a 1992 interview, he said, “I’m not writing Appalachian stories. I’m just writing something I know or want to tell. I’m a storyteller.” He was certainly fascinated by the people of Appalachia, however. In James Still: Man on Troublesome Creek, a 1988 documentary produced by Western Kentucky University, he said, “If I had to select one theme basic to the lives of the people here, I think it is the will to survive any difficulty, any sorrow, any condition. I have seen them do it … and I admire that.”

In The Hills Remember, sorrows come thick and fast. In the title story, old Aus Hanley, “meanest man on Troublesome—aye on God’s green earth,” may be down—literally lying on his back on the creek bank, the victim of a fatal gunshot wound—but he is by no means out, as his assailant discovers to his regret during the half hour or so that it takes Aus to die. In “All Their Ways Are Dark,” a fiercely protective mother burns down her own house rather than suffer the company of her husband’s ungrateful, freeloading relatives for one more day. “Lost Brother” relates the story of a well-meaning fiddle player, plagued with guilt over the accidental shooting of his own son, who adopts a young man Still describes as “all the devils in torment rolled in one ball,” with predictably dire consequences.

In The Hills Remember, sorrows come thick and fast. In the title story, old Aus Hanley, “meanest man on Troublesome—aye on God’s green earth,” may be down—literally lying on his back on the creek bank, the victim of a fatal gunshot wound—but he is by no means out, as his assailant discovers to his regret during the half hour or so that it takes Aus to die. In “All Their Ways Are Dark,” a fiercely protective mother burns down her own house rather than suffer the company of her husband’s ungrateful, freeloading relatives for one more day. “Lost Brother” relates the story of a well-meaning fiddle player, plagued with guilt over the accidental shooting of his own son, who adopts a young man Still describes as “all the devils in torment rolled in one ball,” with predictably dire consequences.

Almost without exception, the inhabitants of Still’s fictional landscape live their lives on the stark edge of hunger. In “Twelve Pears Hanging High,” children greedily take in every detail of the bounty that suddenly appears on the kitchen table when their father takes a new job in the coalmine: “There was a five-pound bucket of lard, with a shoat drawn on the bucket. Brown sugar in a glass jar. A square of sowbelly, thin and hairy. A white-dusty sack of flour, and on it a picture-piece of a woman holding an armful of wheat straws. And there was a tin box of black pepper and a double handful of coffee beans. We looked in wonder, not being able to speak, knowing only that a great hunger crawled inside of us, and that our tongues were moistening our lips.”

In these stories, the youngest are particularly vulnerable. A baby’s funeral—postponed until after the harvest has been gathered in—is the occasion for a large family gathering in “The Egg Tree.” The child’s brother describes the poignant scene: “Neighbors came up quietly, greeting Mother, and the women held handkerchiefs in their hands, crying a little. Then we knew again that there had been death in our house. All who went inside spoke in whispers, their voices having more words than sound. The clock was stopped, its hands pointing to the hour and minute the baby died; and those who passed through the rooms knew the bed, for it was spread with a white counterpane and a bundle of fall roses rested upon it.”

In these stories, the youngest are particularly vulnerable. A baby’s funeral—postponed until after the harvest has been gathered in—is the occasion for a large family gathering in “The Egg Tree.” The child’s brother describes the poignant scene: “Neighbors came up quietly, greeting Mother, and the women held handkerchiefs in their hands, crying a little. Then we knew again that there had been death in our house. All who went inside spoke in whispers, their voices having more words than sound. The clock was stopped, its hands pointing to the hour and minute the baby died; and those who passed through the rooms knew the bed, for it was spread with a white counterpane and a bundle of fall roses rested upon it.”

The keys to survival in such an environment are hard work and lots of luck. Still describes both the opportunities and the disappointments produced by risky and undependable jobs in coal mining, logging, farming, saw-milling, and even well-cleaning. In “The Hay Sufferer,” a wiry little man descends to the depths of a well, where “the mud on the bottom reached to the caps of his knees,” and proceeds to scoop mud and clay from the surface into a bucket with his hands. He enjoys his work, as the bottom of a well is the only place where his allergies don’t bother him. “When the last of the mud had been removed,” Still writes, “the well cleaner hand-walked the rope to strip away the honeyvines, and he used a finger as a spindle upon which to wind the spiders’ webs.” Last, he sprinkles table salt on the bottom before declaring, “A wonder all that gom didn’t give you a disease.”

“Gom,” or mess, is an example of the vocabulary common among Still’s neighbors, and his stories are filled with what Olson calls Still’s “brilliant literary approximation of Appalachian speech.” Olson includes a link to a handy database containing definitions for hundreds of Appalachian words such as “rusty” (a prank), “witty” (a slow-witted person), and “sang” (ginseng root).

Despite the hardships, or perhaps because of them, Still’s characters make the most of happy times, with community gatherings for sorghum making, hog butchering, barn dances, and weddings. Humor is often enjoyed by one character at the expense of another, and colorful metaphors and similes are scattered liberally through the stories to comical effect. In “The Scrape,” characters climb ground “so steep you’d nearly skin your nose” and have heads “as hard as ball-peen hammers.” In “On Pigeon Roost Creek” the bewitching Ellafronia Saul is “tender as a snail’s horns” with teeth “white as ladybean seeds and even-set as corn grains on a nubbin.” In “School Butter,” a schoolhouse full of children listening entranced to the story of the Trojan Horse are “still as moss eating rocks,” and in “Plank Town” a child is “so spoiled salt wouldn’t save him.”

Despite the hardships, or perhaps because of them, Still’s characters make the most of happy times, with community gatherings for sorghum making, hog butchering, barn dances, and weddings. Humor is often enjoyed by one character at the expense of another, and colorful metaphors and similes are scattered liberally through the stories to comical effect. In “The Scrape,” characters climb ground “so steep you’d nearly skin your nose” and have heads “as hard as ball-peen hammers.” In “On Pigeon Roost Creek” the bewitching Ellafronia Saul is “tender as a snail’s horns” with teeth “white as ladybean seeds and even-set as corn grains on a nubbin.” In “School Butter,” a schoolhouse full of children listening entranced to the story of the Trojan Horse are “still as moss eating rocks,” and in “Plank Town” a child is “so spoiled salt wouldn’t save him.”

As colorful as the characters is the Appalachian landscape itself. A good example is “The Ploughing,” in which the young narrator goes to the fields seeking his Uncle Jolly early on an April morning. Still writes, “The sky was as blue as a bottle. A rash of green covered the sheltered fence edges, though beech and leatherwood were browner and barer still for the sunlight washing their branches. I began to climb, hands on knees, the way being steep. I went up through a redbud thicket swollen with unopened bloom and leaf, coming at last to where Uncle Jolly was ploughing. The bench spread back to a swag, level as creek land, set up against air and sky and nothing.” Later, when Uncle Jolly decides to let his eager nephew try his hand, the experience takes on a mythical quality: “The earth parted; it fell back from the shovel plough; it boiled over the share. I walked the fresh furrow, and balls of dirt welled between my toes. There was a smell of old mosses, of bruised sassafras roots, of ground new-turned. . . . The share rustled like drifted leaves. It spoke up through the handles. I felt the earth flowing, steady as time.”

The best writers are able to arrange words on a page so skillfully that they somehow open a channel directly between the author’s voice and the reader’s heart. James Still was such a writer, and his deceptively simple portrayals of Appalachian life pulse with a powerful truth and an eloquent beauty. With The Hills Remember, his voice will continue to resonate as clear and as pure as a dipperful of cold mountain water on a hot day.

To read Chapter 16’s review of Chinaberry, James Still’s posthumously published final novel, click here. To read a sample poem from Ted Olson’s own recent poetry collection, Revelations, click here.