The Beat Goes Down

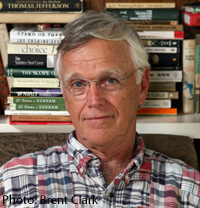

Clyde Edgerton brilliantly captures the complex dance of music and race in a small Southern town in 1963

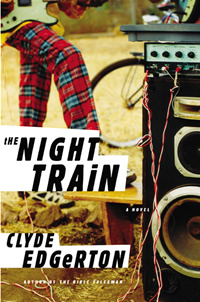

Like many Southern towns in 1963, Starke, North Carolina—the setting of Clyde Edgerton’s tenth novel—is divided by a railroad running north to south. East of the track is white and mostly poor; west is black and mostly poorer. Yet even in a novel that opens the very week Martin Luther King Jr. sat in a Birmingham jail and wrote a letter, the residents of Starke are tied to one another in deep and complex ways. “People from both sides of the track in Starke ate about the same amount—per capita—of corn bread, chicken, vegetables, pork, pies, cakes, stews,” Edgerton writes in The Night Train. “More chitterlings on the west side. About even on chicken necks, per capita. You could hear ‘Pass me that corn bread’ from one house. ‘Mama, can I have the snap beans?’ from another.”

Edgerton notes other similarities among the people of this segregated town: “We could accurately say that the railroad divided a community of corn bread, vegetable, and chicken eaters; or a community of pet lovers; or a community of rural dialects; of families with men who hunted quail and rabbits; people who owned chickens; women who cooked and sewed; or people who had, in their lifetimes, ‘worked in tobacco’—picked it, carted behind mule or tractor, tied it to sticks, hung it in barns to cure, took it to the market, complained about suckering and land lugging.”

But the track-crossing similarity that most concerns Edgerton is music. At barely 200 pages, The Night Train is his shortest book, and yet in its simple story of two musically inclined teenagers, one white and one black, it may surpass Walking Across Egypt and The Bible Salesman as his best. The title come from the blues song as sung by James Brown in his groundbreaking 1963 album, Live at the Apollo. The novel’s black protagonist, Larry Lime Beacon of Time Reckoning Breathe on Me Nolan (his family is known for long names) is sixteen and learning to play piano blues from a hemophiliac musician called The Bleeder. The other protagonist, Dwayne Hallston, is the same age and white. Dwayne has put together a rock-and-roll band in hopes of playing for The Brother Bobby Lee Reese Country Music Jamboree, a local television show patterned on the Grand Ole Opry or, failing that, for frat parties at the college town down the highway. The two boys work together at one of Starke’s major employers, a furniture-refinishing business. (The other is a dog food factory; both are owned or primarily funded by the town’s sole rich man, who also owns the local television station where Dwayne aspires to perform.).Their mutual interests lead Larry Lime and Dwayne to an uneasy friendship that reflects the changing nature of the times.

But the track-crossing similarity that most concerns Edgerton is music. At barely 200 pages, The Night Train is his shortest book, and yet in its simple story of two musically inclined teenagers, one white and one black, it may surpass Walking Across Egypt and The Bible Salesman as his best. The title come from the blues song as sung by James Brown in his groundbreaking 1963 album, Live at the Apollo. The novel’s black protagonist, Larry Lime Beacon of Time Reckoning Breathe on Me Nolan (his family is known for long names) is sixteen and learning to play piano blues from a hemophiliac musician called The Bleeder. The other protagonist, Dwayne Hallston, is the same age and white. Dwayne has put together a rock-and-roll band in hopes of playing for The Brother Bobby Lee Reese Country Music Jamboree, a local television show patterned on the Grand Ole Opry or, failing that, for frat parties at the college town down the highway. The two boys work together at one of Starke’s major employers, a furniture-refinishing business. (The other is a dog food factory; both are owned or primarily funded by the town’s sole rich man, who also owns the local television station where Dwayne aspires to perform.).Their mutual interests lead Larry Lime and Dwayne to an uneasy friendship that reflects the changing nature of the times.

What Clyde Edgerton has to say about the nature of race relations in the South of the early 1960s tends to be conveyed through drama, not through exegesis; he requires readers to figure out on their own the significance of events and conversations in the book. The exception is one brilliant passage that concludes his catalog of similarities between the white and black sides of town: “Since about the same percentage of people called themselves Christians on both sides of the track, we could say that the railroad track divided a single Christian community. But something begins to break down there, doesn’t it? The truths of their pasts gave each group a different God (one of deliverance, the other of dominion), a different mode of worship service (one with energy and joy trumping solemnity and fear, the other almost reversing that). And their histories brought hardships to the people of West Starke not understood by the people of East Starke, and guilt to the East not understood by anybody—a guilt that if moving deep in a lake, would leave the flat surface calm.”

One Sunday night in May 1963, that flat surface is disturbed by a surprising confluence of music—the precise moment in time when both Motown and The Brother Bobby Lee Reese Country Music Jamboree cross the tracks. In a couple of flash-forward chapters set in 2011—when the keyboard player of Dwayne’s band is researching an article for the annual music edition of The Oxford American—readers learn that Brother Bobby Lee Reese is uniquely positioned to shake up his audience. This promise is fulfilled when Dwayne’s band is scheduled to play two live gospel songs but plays something else instead.

One Sunday night in May 1963, that flat surface is disturbed by a surprising confluence of music—the precise moment in time when both Motown and The Brother Bobby Lee Reese Country Music Jamboree cross the tracks. In a couple of flash-forward chapters set in 2011—when the keyboard player of Dwayne’s band is researching an article for the annual music edition of The Oxford American—readers learn that Brother Bobby Lee Reese is uniquely positioned to shake up his audience. This promise is fulfilled when Dwayne’s band is scheduled to play two live gospel songs but plays something else instead.

As with everything Clyde Edgerton writes, The Night Train is very funny. The jokes arise naturally from familiar situations; Edgerton cares too much for each of his characters to let any of them devolve into cliché or metaphor. Even minor characters (notably the elderly on either side of the tracks) remain both humorously and heartbreakingly real, playing against type in small but satisfying ways. While the general plot—a train rolling toward a comic blending of cultures—seems apparent from the start, the story, like its characters, contains enough surprise to bring delight at every turn.

“Are you ready for the Night Train?” James Brown shouts at his New York audience several times during his 1963 song. The people of Starke, North Carolina, aren’t quite ready for it—but it is screaming down the tracks anyway, blurring in its wake the once immutable border that the tracks themselves represent. As it passes, the reader realizes that Edgerton’s novel is less about race than about the joyous, transformational power of song.

Clyde Edgerton will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.