The Bitter Taste of Sugar

Attica Locke’s new literary thriller is much more than a murder mystery

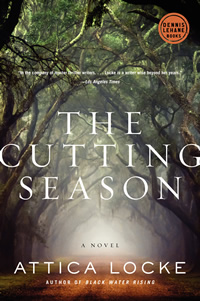

The Cutting Season, the second literary thriller from Attica Locke, opens with a murder: the body of an El Salvadoran sugarcane field worker, her throat slit, is found in a shallow grave on the grounds of Belle Vie, an antebellum plantation that’s now a tourist attraction and event site. Just across a fence line from that grave are Belle Vie’s back acres, leased for cane farming to the Groveland Corporation, which is steadily swallowing up land in Louisiana’s Ascension Parish.

Belle Vie’s manager, Caren Grey, grew up on the plantation grounds: for decades her late mother had been the cook. Returning to Belle Vie with her ten-year-old daughter Morgan, after years away, is not a move Caren has made without ambivalence: “Pride, as a method of categorizing one’s personal life and history, was something she’d long given up on,” Locke writes. But she has always known the plantation as a safe place, one to which she has real ties. As clues about the murder begin to surface, Caren sees her vision of Belle Vie’s future, and her own shaky sense of security, begin to crumble.

Locke, who brings to the page an accomplished resume in writing for television and film, made an auspicious debut in 2009 with her first novel, Black Water Rising, which was shortlisted for the 2010 Orange Prize and earned her comparisons to mystery-masters Dennis Lehane and Scott Turow. Now it’s Lehane himself who has heralded Locke as a formidable new talent on the scene, having selected The Cutting Season as the first title for his new HarperCollins imprint.

Locke recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email prior to her appearance at the Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 12–14.

Chapter 16: Before you published your first novel, Black Water Rising, you were an established Hollywood screenwriter—for Paramount, Disney, Warner Bros, HBO, and others. Is there any facet of screenwriting that serves as an especially useful training ground for writing novels?

Chapter 16: Before you published your first novel, Black Water Rising, you were an established Hollywood screenwriter—for Paramount, Disney, Warner Bros, HBO, and others. Is there any facet of screenwriting that serves as an especially useful training ground for writing novels?

Locke: For me, it’s having an appreciation for “white space” on the page—leaving some things unexplained. In plays and screenplays (and often in real life), the real meaning between two lines of dialogue is what isn’t said. I try to leave moments like that in my books.

Chapter 16: What first appealed to you about the idea of writing a novel?

Locke: Mainly the idea that writing a novel seemed so possible. Whereas making a movie involves millions of dollars, months and years of fundraising, a cast and a crew. There was a directness of approach that I liked about writing a novel. I wanted to tell a story, and I only needed paper to do it.

Chapter 16: Oak Alley Plantation, a real place in Louisiana, is the model for Belle Vie; you’ve described it as a “muse at first sight.” What was so compelling about this particular setting for a novel?

Locke: Well, I had never been on a plantation before, and I wasn’t prepared for my emotional reaction. I burst into tears the moment I set foot on the land. I was thrown by the undeniable beauty of the place, mixed with what it represented for me, as an African-American. I was also stunned by the absurd kitschy-ness of it all. There were literally women dressed up as mammies there to greet the wedding guests. Oak Alley has a restaurant, a gift shop, a bed and breakfast. I didn’t know if we were helping or hurting our history by preserving it in this way.

Chapter 16: In her New York Times review , Janet Maslin writes that both you and Dennis Lehane “use the murder mystery as a framework for much more ambitious, atmospheric fiction.” What draws you to mystery? Do you agree with Maslin that it offers a way to ease readers into complex social and historical issues?

Locke: I agree with her that the genre is a good fit for exploring social issues. The plot restraints of a murder mystery keep me from going off on tangents or getting too preachy and didactic. And I do think the familiar tropes of a mystery make it more palatable for readers to sit with new or uncomfortable themes.

Chapter 16: In researching the sugar industry, what did you find most intriguing or surprising about that world?

Locke: The strangest thing for me was seeing one of the manufacturing plants—pieces of cane turned into this coarse white powder that they store in warehouses. This is before it goes to a final processing plant, so nothing’s been bleached or made pretty; there’s just a big pile of white sugar sitting like a sand dune in a warehouse. Walking in, you get this sticky black stuff on the soles of your shoe—sugar mixed with dirt, I guess. And the whole operation stinks! It’s a scent that’s so sweet, it’s actually sour.

Locke: The strangest thing for me was seeing one of the manufacturing plants—pieces of cane turned into this coarse white powder that they store in warehouses. This is before it goes to a final processing plant, so nothing’s been bleached or made pretty; there’s just a big pile of white sugar sitting like a sand dune in a warehouse. Walking in, you get this sticky black stuff on the soles of your shoe—sugar mixed with dirt, I guess. And the whole operation stinks! It’s a scent that’s so sweet, it’s actually sour.

Chapter 16: Caren Gray is in a complicated position as an African-American woman managing a largely African-American staff on a plantation, owned by a white family, which has become a tourist draw for its re-creation of the plantation South. The staff sees Caren as “management, with a capital M” and feels profoundly alienated from her. Can you talk a bit about the development of this fascinating character?

Locke: She came out of my research, in the sense that once I knew I was going to write about Oak Alley or a place like it, I started doing a lot of research about sugar plantations, and I came across a book of letters from a plantation mistress to her mother in the years before, during and after the Civil War. And what surprised me most is that, in 2009, when I read the book, I actually had more in common with the plantation mistress than I did with the slaves. I was a middle class woman working out of my home, and I had people helping me raise my daughter—women who were of a different culture than me, spoke a different language and whom I wasn’t sure trusted me all that much. Somewhere in the experience of reading that book was the idea to explore the irony of a black woman running a plantation.

Chapter 16: The Cutting Season is set during the early part of the Obama Administration, and Eric, the father of Caren’s daughter, has ties to Obama. That fact adds a layer of irony to the plantation backdrop, but is there a political subtext to this plot point as well?

Locke: I don’t know that it’s political so much me trying to set the book in a certain time frame, in terms of our country’s cultural history. Barack Obama’s election was a very big deal, no matter what side of the political equation you fell on. I wanted readers to think about what it meant to have crossed the psychological threshold of having a black president. And how does (or doesn’t) his presidency mitigate the history of slavery in this country?

Attica Locke will discuss The Cutting Season at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books on October 12 at 2 p.m. in Conference Room 1A of the Nashville Public Library. All festival events are free and open to the public.