“The Bridge”

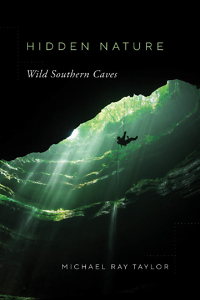

Book Excerpt: Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves

It was an Indiana Jones sort of moment, stolen from a hundred adventure films: that part where the heroes race over a collapsing stone bridge.

I was not yet thirty years old that summer in the late 1980s. Children were still in the future. Kathy and I had met up with Lee and Sharon Pearson in Cookeville, something we often did on vacation. By this time our wives seldom went caving, but Lee had somehow convinced them to join us in a short trip to a well-known, heavily-visited wild cave about forty-five minutes from town.

“Nothing but easy walking passage,” he promised. “Pretty formations.”

“It’s probably some hellhole with a belly crawl,” Sharon said.

But Lee insisted it would be fun, and, surprisingly, Sharon and Kathy agreed to go. We drove from Cookeville down a scenic county road along the edge of the Plateau. Through gaps in the trees and the haze of summer we could see rolling farmland and the twin ribbons of Interstate 40 before we turned south toward forest. We parked in a darkly shaded dirt lot just off the highway. The hike was short, with dramatic spires of weathered gray limestone rising through green brush beside us. The entrance appeared exactly as advertised: a tall portal to an easy walking passage.

We all donned helmets and lamps. The cool cave air was far more appealing than the rising heat and humidity outside. For perhaps two hours the four of us meandered through a limestone canyon about twenty feet wide, the sort of twisting, boulder-strewn pathway a cowboy would gallop down in a western, if it were outside. Occasionally we passed deep holes in the floor, but we easily skirted these by walking to one side. At a wide junction area, Lee and I left our spouses sitting on a large rock, eating snacks. He explained that he and I would spend a few minutes scaling one wall of the canyon visible from the point where they sat.

“Just ten minutes or so,” he promised. “There’s a lead I’ve always wanted to check.”

A couple of shadowy pockets in the wall beckoned, a good fifty feet off the floor. Even though we had chosen a well-known, well-traveled cave, the general inaccessibility of these high leads might signal previously unexplored side passages. Lee picked out a series of handholds and footholds and began ascending the wall. I followed. We finally reached the two openings, but both revealed dead ends. A lone boot print told me we weren’t even the first to check them out. So we edged along the wall, clinging by our fingertips to various indentations as we began slowly to working our way back toward the floor.

Ahead, Lee pointed out a natural arch that joined the two sides of the canyon. From the main trunk below, this connection had appeared to be an uneven patch of ceiling, rather than the bridge now visible from our higher perch. I flipped on the battery-consuming hi-beam of my headlamp. It seemed an easier route than the way we had come up. Lee said that the far side of the canyon was near a known formation alcove — one I thought we might have visited years earlier. I recalled that a much-traveled path, almost a natural staircase, led down toward the floor from the alcove, which glistened with yellow and white stalactites. It would land us in the main passage very close to the spot where we had left Kathy and Sharon.

We decided to avoid the exposed, somewhat dicey-looking down-climb by walking over to the other side.

We decided to avoid the exposed, somewhat dicey-looking down-climb by walking over to the other side.

Kathy and Sharon could see what we were up to from where they sat. Kathy recalls shouting toward us, “Don’t try to go across that, you dumbasses!”

I don’t recall hearing her.

Whenever constructions of nature sit for centuries undisturbed by weather or the hand of man, they may not be as immovable as they appear. A third of the way across the three-foot-wide arch, something shifted slightly beneath our feet. We froze.

Lee, leading as usual, turned toward me, a quizzical look on his face.

“That can’t be good,” I said.

Just then a chunk of limestone the size of a Pilates ball rolled off one side of the arch, followed by gravel sliding from a spot we had just passed. We ran as more chunks of bridge collapsed behind us to sounds of thunder. Powdered limestone rose through the air like smoke from an explosion. Lee reached the far side ahead of me. I was still a few steps behind, the path tilting beneath my feet like a gym treadmill moving toward a more difficult setting. Had there been an accompanying soundtrack, the music would have swelled ominously, horns blaring danger. I was two long strides away from solid ground and took a leap of faith.

***

Cavers will tell you that most injuries underground happen to ill-equipped spelunkers, that proper training and equipment make even extreme vertical caving a relatively safe activity. This is true, by and large: according to actuarial tables, you are less likely to die while caving than while participating in, for example, hang gliding, scuba diving, or boxing. Highly publicized cave accidents, like the boys trapped in Thailand who drew the world’s attention for a week in 2018, generally involve novices overlooking basic safety precautions. And it’s true that standard single-rope technique, first developed by cavers in the late 1960s to safely descend the deep pits of TAG*, is so reliable that it has been adopted by rescue squads and SWAT teams the world over. Even the leading ropes for mountaineering and rescue operations — the brands PMI and Bluewater — were first manufactured in north Georgia specifically for caving. (“PMI” stands for “Pigeon Mountain Industries,” named after the mountain housing Ellison’s Cave, which contains the two deepest vertical cave pitches in the continental United States: Fantastic Pit, at 586 feet, and Incredible Pit, at 440 feet.)

But the reality is that caves are an ever-evolving and naturally unstable environment. Serious injury, even death, may be no more than a misstep away. American Caving Accidents, published periodically by the National Speleological Society and continually updated online, offers a sobering compendium of the many ways things can go wrong underground. It is thus required reading for beginning cavers.

***

Not that I was thinking about making that particular publication as the bridge collapsed beneath my feet. I leapt without thinking, landing solidly on the flat surface where Lee stood. We heard urgent shouting from Sharon and Kathy, some distance safely beyond the boulders. Gravel still rained down on the obscured floor.

“We’re okay!” Lee answered. “We made it across.”

As the dust cleared, I could see that the natural arch still stood — just a little bit smaller than it had been a few minutes earlier. Our wives waited in the canyon, not directly below the boulder storm we had created, but close enough to have heard the crash and seen the dust cloud, to have wondered whether we had killed our fool selves.

We had not. As this sank in, we grinned like madmen. We looked at the pretty stalactites and stalagmites in the alcove ahead before climbing down the gentle route to the main passage, where they waited to yell at us.

“You know, Mike,” Lee said as we walked, “that’s caving.”

*An acronym for the cave-rich region surrounding the intersection of Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Michael Ray Taylor. Reprinted with the permission of Vanderbilt University Press. All rights reserved. Michael Ray Taylor’s Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves will be published in August 2020. He chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas.