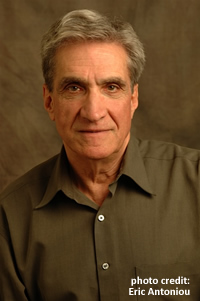

The Bruce Springsteen of American Poetry

Robert Pinsky, America’s preeminent Man of Letters, talks with Chapter 16 prior to his Chattanooga appearance next week

Poet, translator, critic: these are Robert Pinsky’s day jobs. After hours, he dabbles: as columnist, professor, Poet Laureate. And even that’s just for starters. As Poet Laureate, Pinsky founded the wildly popular Favorite Poem Project; on television, he appears frequently on serious shows like PBS’s NewsHour but has also turned up on The Simpsons and The Colbert Report; and as a musician, he performs with jazz bands, recently wrote the libretto for an opera, and shared the stage with Bruce Springsteen. If America can claim a Public Man of Letters, Pinsky is it.

Born into a working-class family in Long Branch, New Jersey, in 1940, Pinsky, never a strong student, nevertheless became the first in his family to attend college, enrolling at Rutgers. He has said he found his calling while copying out by hand William Butler Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium.” After graduating from Rutgers, he enrolled at Stanford to study poetry with Yvor Winters. More than a decade later, at thirty-five years old, he published his first book, Sadness and Happiness. Since then he has published six more poetry collections, three books of criticism, and English translations of the great Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, as well as Dante’s Inferno. He now serves as poetry editor of the online magazine Slate and also teaches in the graduate writing program at Boston University.

Pinsky’s own great poems blend the personal with the universal, the present with the past and the future. This mingling helps him convey a sense of both urgency and timelessness. A good example is his poem “Shirt,” in which an ordinary, mass-produced garment undergoes the scrutiny normally reserved for works of art. In the poem, the shirt’s history becomes inseparable from the histories of the men and women who produce it. The poem includes these haunting lines about the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911:

Pinsky’s own great poems blend the personal with the universal, the present with the past and the future. This mingling helps him convey a sense of both urgency and timelessness. A good example is his poem “Shirt,” in which an ordinary, mass-produced garment undergoes the scrutiny normally reserved for works of art. In the poem, the shirt’s history becomes inseparable from the histories of the men and women who produce it. The poem includes these haunting lines about the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911:

…[A] young man helped a girl to step

Up to the windowsill, then held her out

Away from the masonry wall and let her drop.

And then another. As if he were helping them up

To enter a streetcar, and not eternity.

A third before he dropped her put her arms

Around his neck before she kissed him. Then he held

Her into space, and dropped her.

Pinsky will give a free public lecture, “The Value of the Arts and Humanities in Education and Society,” at the University of Tennessee in Chattanooga on February 7. Prior to his visit, Pinsky answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You have written, “Attachment to a work of art, as to a person or a cuisine or a sport, begins with a physical experience, and only afterward proceeds to analysis and interpretation.” How do you hope readers physically experience your poems?

Robert Pinsky: I hope that they will try my poems in their own voices—at least imagining what it’s like to say the words, and even better actually saying them, appreciating what it feels like to need to say this in just these words. The exact model is in the videos at favoritepoem.org: readers who are not actors or poets or professors, but . . . readers.

Robert Pinsky: I hope that they will try my poems in their own voices—at least imagining what it’s like to say the words, and even better actually saying them, appreciating what it feels like to need to say this in just these words. The exact model is in the videos at favoritepoem.org: readers who are not actors or poets or professors, but . . . readers.

Chapter 16: In each of your monthly Slate columns, you reprint a classic poem and, after some contextual background and explication, engage in a conversation about it. Readers get your insights, as they might in a poetry class, and then participate in a fairly learned poetry discussion with you and other readers. It’s impossible not to be both instructed and entertained. Would you talk a bit about how the column has developed, and about any hopes you have for its future?

Pinsky: The “Classic Poem” columns include my introduction of a poem by the likes of Emily Dickinson or Gerard Manley Hopkins, most recently Herman Melville, an audio file of me reading a poem, and of course the text of the poem. And then, the Discussion: comments, arguments, notes, and speculations by a readership that might include well-known poets and high school students, scholars and mockers, insiders and outsiders. There are some regulars who contribute a lot—responding to the weekly new poem, as well as the monthly “Classics.” I respond to the discussion—and I’m happy to say it is more civilized and decent in tone than a lot that happens on the Web.

Chapter 16: Hart Crane wrote, “The writing of a poem is not—as the writing of a chemical equation is—intended to describe anything; instead, the poem is the chemical reaction itself.” And you’ve written that “a poem is something that happens.” How can a poem be a “chemical reaction”? How can a poem “happen”?

Pinsky: Like a piece of music, a poem happens in time: you can’t say all the syllables at once; they come out of your mouth in a certain order. When you say the poem—if it’s by, say, John Keats—your pronunciation may be different from his, but you are saying the words and lines in the same order as he said them. But your voice and body and you, all your differences from him or any other reader, all that creates a “chemical reaction” between the reality of the poem and the unique reality of you saying it and perceiving it. Once again, the videos at favoritepoem.org provide an example of this.

Pinsky: Like a piece of music, a poem happens in time: you can’t say all the syllables at once; they come out of your mouth in a certain order. When you say the poem—if it’s by, say, John Keats—your pronunciation may be different from his, but you are saying the words and lines in the same order as he said them. But your voice and body and you, all your differences from him or any other reader, all that creates a “chemical reaction” between the reality of the poem and the unique reality of you saying it and perceiving it. Once again, the videos at favoritepoem.org provide an example of this.

Chapter 16: In 2010, at Fairleigh Dickinson University, you and Bruce Springsteen, fellow New Jerseyans, appeared on stage together—Springsteen the poet-turned-musician, you the musician-turned-poet. It’s hard to believe that it took this long for you two to get together. Is Bruce Springsteen the Robert Pinsky of rock and roll?

Pinsky: Bruce and I come from the same part of the world, literally and figuratively. As that occasion showed, there are some similarities between what he does in his idiom and what I do in mine. We had a good time, have talked about doing that again some day.

Chapter 16: You are a much-honored poet, translator, and critic, as well as a widely read essayist and columnist, and you’ve repeatedly appeared on television. You have said that poetry itself is too foundational, too integral to people’s daily lives, to need a spokesperson, but it could easily be argued that you play exactly that role yourself. Do you see it as at all culturally meaningful or valuable for the country to have poets contributing to the public conversation?

Pinsky: To me, there’s something ephemeral or unreal about a lot of cultural activity that is official or visible or media-generated or organizational. It may be fun (or not). But quiet, unnoticed streams, underground streams, may run deeper and last longer: something a good teacher or loving parent reads to someone, or something somebody reads. I’m a little skeptical of arts-boosterism, poetry-boosterism . . . I hope that those Favorite Poem Project videos and events point in a different direction.

Pinsky: To me, there’s something ephemeral or unreal about a lot of cultural activity that is official or visible or media-generated or organizational. It may be fun (or not). But quiet, unnoticed streams, underground streams, may run deeper and last longer: something a good teacher or loving parent reads to someone, or something somebody reads. I’m a little skeptical of arts-boosterism, poetry-boosterism . . . I hope that those Favorite Poem Project videos and events point in a different direction.

Chapter 16: William Carlos Williams, another fellow New Jerseyan, struggled to write about the lives of poor and working people without sentimentality and in a distinctly American dialect. In that sense, he might be called a political poet. Do you see your own work in that vein or locate yourself within that tradition?

Pinsky: I’d be honored to think I was in the Williams tradition. To be hoped-for, not claimed!

Chapter 16: When you are in a bookstore choosing a new book of poems to read for pleasure only, what helps determine your choice? Do you flip through the pages, taking in a few lines here, a couple of stanzas there? Do you read the blurbs on the back? Does the physical look and feel of the book influence you?

Pinsky: I turn to a poem and imagine saying it out loud. I might even mumble it aloud. Not in an actor or poetry-reading way . . . just to hear the rhythms and pitches, how the vowels and consonants and lines and sentences are working together. Or not.

Robert Pinsky will give a free public lecture, “The Value of the Arts and Humanities in Education and Society,” sponsored by the University of Tennessee and the Benwood Foundation in Chattanooga, on February 7 at 7 p.m. in the Roland Hayes Auditorium of the UTC Fine Arts Building. The event is free and open to the public. Doors will open at 6 p.m. Seating is limited and on a first-come, first-served basis.