The Constancy of Goodness

Robert Goolrick, author of the bestseller A Reliable Wife, talks with Chapter 16 about writing as the path to something resembling peace

Robert Goolrick grew up in the 1950s in a small college town in Virginia, where he lived with his charismatic father, a college professor; his beautiful mother, a homemaker; and two siblings. When Goolrick lost his job as an advertising copywriter, he turned to writing memoir. The End of the World As We Know It (Algonguin, 2007) shines a searing spotlight on the excesses and failures of both the social underpinnings of the time and his own parents’ inevitable alcohol-fueled decline, culminating in a devastating portrayal of the sexual abuse he suffered as a child.

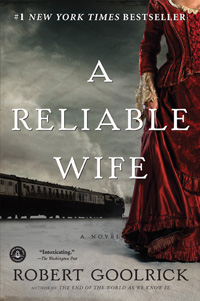

Three years later, Goolrick’s first novel, A Reliable Wife (Algonquin, 2010), quickly garnered both critical and popular acclaim, became a favorite book-club selection, and hit the top spot on The New York Times bestsellers list. In A Reliable Wife, Goolrick spins a web of mystery and suspense around deceitful lovers in a bleak, early-twentieth-century Wisconsin town in the dead of winter.

Goolrick’s soon-to-be-published second novel, Heading Out to Wonderful (read an excerpt here), begins with the arrival of a mysterious stranger, Charlie Beale, in a quiet Virginia town during the summer of 1948: “It was a town where people expected to live calmly and die and go to heaven in due time.” Beale brings with him two suitcases—the first filled with knives and the second with money—and a powerful desire that “things would finally turn out better, and that this would be the place he could feel at home.”

Goolrick’s soon-to-be-published second novel, Heading Out to Wonderful (read an excerpt here), begins with the arrival of a mysterious stranger, Charlie Beale, in a quiet Virginia town during the summer of 1948: “It was a town where people expected to live calmly and die and go to heaven in due time.” Beale brings with him two suitcases—the first filled with knives and the second with money—and a powerful desire that “things would finally turn out better, and that this would be the place he could feel at home.”

Prior to his appearance at Parnassus Books in Nashville on March 15, Robert Goolrick answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: You began your writing career at age fifty-three, after losing your job in advertising. Has literary success changed your life? Is pursuing a new career at mid-life a course you recommend?

Goolrick: I changed careers because I had no choice. It was agonizing and not easy, but, looking at the results, it’s the best thing that ever happened to me. People had always told me I should be a writer; now I am.

Chapter 16: Explaining the impetus to write a memoir, you have said, “My clothes were immaculate, my house charming, and my dinner parties a success, yet inside I felt completely dead. I found that writing about my life was a way of saving what’s left.” Are you willing to elaborate on that point at all?

Goolrick: Adults who were abused as children often function at a very high level. It’s the mechanism we develop to conceal and manage the fear that governs our lives. People often ask me if writing the memoir was cathartic. It wasn’t, because I was only recording what I already knew. But what was extremely redemptive was seeing it on a shelf in a bookstore. I had made my experience into an object which was entirely separate from me, and that gave me an enormous sense of both vindication and pride.

Goolrick: Adults who were abused as children often function at a very high level. It’s the mechanism we develop to conceal and manage the fear that governs our lives. People often ask me if writing the memoir was cathartic. It wasn’t, because I was only recording what I already knew. But what was extremely redemptive was seeing it on a shelf in a bookstore. I had made my experience into an object which was entirely separate from me, and that gave me an enormous sense of both vindication and pride.

Chapter 16: Some reviewers of A Reliable Wife used descriptions such as “Gothic potboiler” in the context of generally positive reviews. How do you react to descriptions of that kind, and how would you characterize the book?

Goolrick: I have to confess I have never read any of the great Gothic novels—Jane Eyre, for instance. It’s a genre of which I am almost totally ignorant. And I don’t read potboilers. It doesn’t bother me to be included in that bunch, but I think in many ways that A Reliable Wife was misread by many of its readers. Those who expected a stereotypical bodice-ripper are generally disappointed, I think. A Reliable Wife is not actually an historical novel; it is neither Gothic nor a potboiler. I look at it as a very contemporary novel about modern people who happen to live a hundred years ago.

Chapter 16: Michael Lesy’s 1973 cult classic Wisconsin Death Trip was a strong influence on the atmosphere of A Reliable Wife. Was there a similar inspiration for your forthcoming novel?

Goolrick: The new novel is based on a true story. It actually happened, and I knew some of the people involved. It happened a long time ago in a foreign country, but the novel is, in its essential elements, a true story. It was actually harder, I think, to write a novel based on real events than it was to write one that was pure fiction. I felt the obligation to honor the people who had lived through these events, and a real need to understand and communicate the reasons they acted as they did.

Chapter 16: In light of the painful disclosures of your memoir, these lines from Heading Out to Wonderful seem particularly poignant: “Anyway, it’s too late now to go back, to take that rock out of the river, the one that changed the course of the water’s flow.” Has placing rocks in the rivers of your characters’ lives led you to a clearer understanding and acceptance of the pivotal events of your own life?

Goolrick: The final stage of grief is acceptance, or so I understand. Both Sam, in the novel, and I have finally reached a point of acceptance. I live much more in the present and for the future than I ever have in the past. I think that writing this novel was, in many ways, “the rock in the river”—an attempt to re-chart the course of the grief that has ruled my life since I was four.

Goolrick: The final stage of grief is acceptance, or so I understand. Both Sam, in the novel, and I have finally reached a point of acceptance. I live much more in the present and for the future than I ever have in the past. I think that writing this novel was, in many ways, “the rock in the river”—an attempt to re-chart the course of the grief that has ruled my life since I was four.

Chapter 16: In Heading Out to Wonderful, Charlie Beale keeps a diary. Are you a diarist and, if so, how has the habit been helpful to you, and especially to your writing?

Goolrick: I kept a diary when I was a young man. Looking back on it now, re-reading those journals, I see clearly how imprisoned I was in the trauma of the events of my childhood, how repetitious the anguish of those events. I don’t keep a diary or journal now. I write novels instead. When I was a child, I had a recurring constant nightmare in which there was something terribly wrong with me, and I couldn’t speak to describe where the pain was. The journals of my youth were early attempts to find a voice with which to describe the pain. Now I use my writing to elucidate and, I hope, to move beyond that pain.

Chapter 16: The new book is set in a small Virginia town in 1948, which is obviously much closer to your own experience than the 1907 Wisconsin setting of A Reliable Wife. How did you choose the time and place of Heading Out to Wonderful?

Goolrick: There is an actual town of Brownsburg, which the town in the novel resembles only in name. I picked it because I love the real town, and I know it like the back of my hand. Even though the actual events happened in a foreign country, I wanted a setting that was more familiar, and quintessentially Southern. Both of my novels take place in isolated towns. A Reliable Wife was my winter novel; Heading Out to Wonderfulis a summer one. I set it in 1948 simply because that was the year I was born. Nothing more complicated than that.

Chapter 16: In a 2009 interview you said that “most writers really have only one or two things to say in their whole lives. But they can’t get it out, so they construct elaborate memory palaces to house the simple sentence that they’re trying to say. And then, when they finish whatever they’re working on, they say, ‘No, that wasn’t quite it.’ And so they have to write another one.” Are you trying to say something different with Heading Out to Wonderful, or would you say that your message continues to be “I want to be safe and I want to be heard”?

Goolrick: I think I am trying to say that bad things can happen to good people, just as, in A Reliable Wife, good things can happen to bad people. The sentence I am trying to articulate in my life is about the value and constancy of goodness. I’m not sure I’ve said it clearly yet, but I’m getting closer. In writing, I have found the only safe place I have ever known, the only spot in which it is possible for me to understand people’s motivations and to measure my own distance or proximity to what I consider to be the good.

Robert Goolrick will read from Heading Out to Wonderful on March 15 at 6 p.m. as part of Algonquin Book Club Night at Parnassus Books in Nashville. Attendees will sample wines suggested especially for book-club meetings, take home book-club catalogs and complimentary tote bags, and have a chance to win $150 worth of new Algonquin titles.