The Kite

A boy in a coal town finds his way out of the dust

We destroyed three kites trying to get one that could play out every bit of our string in the brisk fall breeze. Then we built the King of All Kites. It was made of kite sticks—broken and unbroken—laced with thin string into a cross shape, and it included double layers of old newspapers carefully stretched and folded over the sticks. The glue bottle with the rubber snout was nearly empty, but the glue had dried, and the kite looked strong. King Kite had a fifteen-foot-long tail made of ripped rags tied tightly into knots at foot-long intervals. The wind was perfect under big puffs of cotton clouds. A short length of lead pipe held all the string we owned laced into a figure eight and ready for the challenge.

We were on the hill at the top of Third Street looking down at the company-owned coal mine. It was named Bovard but everyone called it Crowsnest. I could see the mine owner’s big brick house down at the foot of Second Street; our Catholic Church and the mysterious Protestant Church—each with its two outhouses—were on either side of the brick house. At the other end of First Street I could see the entrance to the coal mine. Aside from the wind, the only noise was the distant clinking of waste coal dumping onto a small tipple below us. The siren on the tipple, which wailed when the mine caved in or caught fire, was silent.

We were on the hill at the top of Third Street looking down at the company-owned coal mine. It was named Bovard but everyone called it Crowsnest. I could see the mine owner’s big brick house down at the foot of Second Street; our Catholic Church and the mysterious Protestant Church—each with its two outhouses—were on either side of the brick house. At the other end of First Street I could see the entrance to the coal mine. Aside from the wind, the only noise was the distant clinking of waste coal dumping onto a small tipple below us. The siren on the tipple, which wailed when the mine caved in or caught fire, was silent.

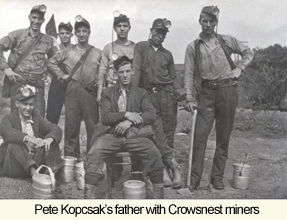

I remembered my father telling me about his first day’s work in the mine. He was sixteen years old, and he’d gone to work with my grandfather. They walked for more than two miles into the dark mine with carbide lamps flickering on their heads before they reached the coal seam that was being worked. My grandfather asked Dad if he wanted to pick or to shovel. Dad decided to pick first. He picked as hard as he could as his father relaxed on his shovel, occasionally scooping the loose coal into the metal car. When Dad tired of picking, he asked to shovel. Soon loose coal was flying from Grandpap’s pick as Dad loaded car after car till he was nearly exhausted. Then Dad heard a loud creaking sound, and Grandpap yelled, “Cave In!” Dad, a high-school track star, sprinted the two miles to the mine exit. As he reached it, a section of the mine collapsed, blowing him onto the ground in a cloud of coal dust. The men outside laughed at him. Fifteen minutes later, Grandpap walked out of the dark dusty hole carrying two picks, two shovels, and two lunch buckets. He turned to Dad and said, “Don’t ever leave your tools behind. It would take us two months to pay back the company store for these tools and lunch boxes.”

We launched the kite into the wind and played out the string as it flew over Second Street. It took two of us to hold the pipe in the gusty wind. When the string was all played out, it looked like the kite was beyond the railroad tracks that hauled the coal to fancy big cities far away. As we reached the end of our string, Scrawny Tommy ran to the houses down Third Street, beating on the screen doors of the clapboard houses and begging for more twine.

I held the pipe and, once in a while, checked the mine entrance for coal dust. We’d gotten a wrinkled yellow telegram from the Army that said Dad had been killed in battle, but then another telegram came and said Dad wasn’t dead at all but was going into surgery in a place called England because a Nazi land mine had blown the toes off one of his feet while he was fighting in France.

I held the pipe and, once in a while, checked the mine entrance for coal dust. We’d gotten a wrinkled yellow telegram from the Army that said Dad had been killed in battle, but then another telegram came and said Dad wasn’t dead at all but was going into surgery in a place called England because a Nazi land mine had blown the toes off one of his feet while he was fighting in France.

Tommy came back with two rolls of twine. It took all three of us to get the end of the string off the pipe and tie the new twine on. Mothers stopped peeling potatoes and scrubbing clothes to stand on bare porches and watch. The kite was getting smaller and smaller. It did not go any higher or lower as we played out more line. Then suddenly the pipe fell limp as the string broke off somewhere in the distance.

We fell on the weeds in front of us and cupped our hands into imaginary telescopes and pressed them to our eyes to watch the kite as long as we could. We thought it would spiral down and crash, but the long broken string still attached to the kite was acting like a steady rudder, and the kite climbed easily and rose and drifted further and further away until we each admitted we could not see it any more.

I got up and started to coil our remaining string back onto the short pipe. The mothers had gone back into their coal-company houses. I had a short piece of lead pipe with some knots of string still on it, but King Kite soared high, leaving Crowsnest to see the big cities far away.

Nashville resident Pete Kopcsak spent his childhood in the coal country of Bovard, Pennsylvania, and his adolescence among the steel mills of Pittsburgh. Before retirement he served as president and CEO of Ingram Materials and Ingram Barge Company. “The Kite” will appear in his forthcoming essay collection, Lies, Memories, Sex, and Coal.