The Music City?

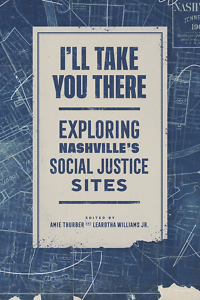

Book Excerpt: I’ll Take You There: Exploring Nashville’s Social Justice Sites

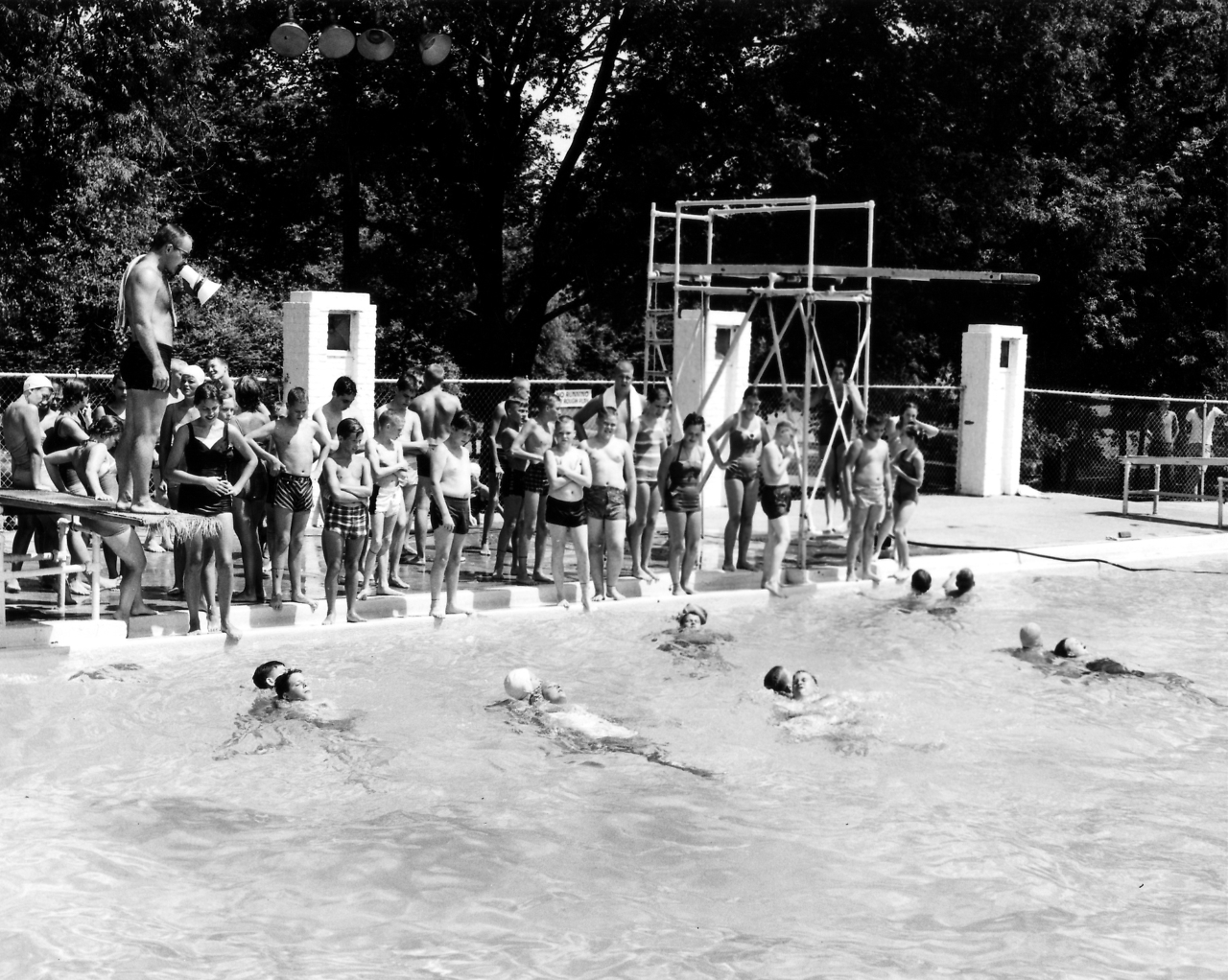

Nashville opened its $623 million, 1.2 million square-foot Music City Center to both fanfare and voices of dissent in May 2013. Its boosters call it a shining monument to the hopes of all who came to the Music City with guitars on their backs and dreams in their hearts. This often-told story of the Music City’s past is one that celebrates tales of smoke-filled honky-tonks, crushed and realized dreams, record stores, dynamic disc jockeys, and the creation of a billion-dollar country music industry. This narrative, though, obscures the fact that historically, Nashville’s diverse musical culture rivaled that of any city in America. Indeed, although there has long been the presence of great musicians in Nashville, it is only since the mid-twentieth century that the city has cultivated its popular image as the center of the country music recording industry. And though Nashville has sparked cultural movements — drawing in and supporting musicians from around the country — it has also nearly extinguished them, burying one of the nation’s most prominent Black music centers beneath a freeway.

I’ll Take You There presents an opportunity to redefine what is meant by the “Music City” moniker in both historical and contemporary times and to explore the often open and contentious conflicts of race and class in the American South. As Nashville gained its reputation as the Music City, two genres of music — both with roots in gospel and Negro spirituals — contested and complemented each other on the Nashville airwaves: country music, which was defined by music industry elites as largely White and conservative, and “race music,” the musical forms associated with African Americans.

Interestingly, at a time when hillbilly was synonymous for poor, rural, White Southerners, Nashville’s elites initially scorned the sounds that earned the city the mantle of the “Hillbilly Music Capitol of the World.” Nashville’s reputation for “hillbilly music” was eschewed until the music began to gain larger audiences as a result of recordings made during the 1920s. During the 1940s and ’50s, programs such as the Grand Ole Opry helped rebrand and popularize the sound as “country music.” Concurrently, Nashville saw the development of “race music” rooted in the musical traditions of descendants of enslaved Africans, who numbered among the earliest settlers in Nashville. The banjo, an instrument created in Africa and one that recent scholarship demonstrates is a common signifier of the Trans-Atlantic experience and Blackness, became a centerpiece of twentieth-century folk, hillbilly, and bluegrass music — all forms that gained acclaim in Music City.

Despite the segregation of musical forms, artists undeniably influenced one another, and the rise of the city’s most celebrated music genre coincided with the growing popularity of rhythm and blues in the South. Nashville’s historic WLAC, whose nighttime fifty-thousand-watt broadcasts during the 1950s did much to increase R&B’s popularity, convinced many in the music industry that they could increase their profits by signing, recording, and producing both country and R&B artists. Music performed by African Americans sometimes resonated in these country spaces, and while most Black artists never succeeded in gaining a foothold in the almost exclusively White genre, as background musicians they nevertheless contributed to its continuing development and to the cultural life of the city.

Indeed, although Nashville’s celebrated status as “Music City, USA” — a term many credit to local WSM-AM radio personality David Cobb — has made the city’s name synonymous with country music, this guide offers insight into the many places and organizations that contributed to its earning this title: from the Fisk Jubilee Singers to the acclaimed Ryman Auditorium, and from the honky-tonks that line Broadway today to the many clubs on Jefferson Street that were destroyed during succeeding waves of so-called urban renewal. Some of America’s greatest songwriters and musicians of all genres have at times called Nashville home, including Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Joan Baez, DeFord Bailey, Gillian Welch, Béla Fleck, and Chris Stapleton. Although the city increasingly celebrates many of the genres that laid the foundation for country music, the contributions of Black musicians to this and other genres are often marginalized. Within the last half of the twentieth century, individuals have challenged the geographical boundaries of what many have defined as the Music City, as evidenced by the eclectic sounds that emanated from the Woodland Sound Studio in East Nashville after 1967, a space that provided an opportunity for Nashboro and Excello Records to produce gospel and R&B records.

There is no doubt that Nashville has earned its musical acclaim. And yet, equating “Music City” with Nashville has functioned to overshadow musical hubs across Tennessee, most notably Memphis, home to Stax Records, one of the most influential soul music record labels in American history. The title of this guide — in addition to reflecting the participatory nature of this text — is a nod to the hit single by the same name. Recorded at Stax and written by Al Bell, originally of Little Rock and later co-owner of Stax, “I’ll Take You There” was made famous by the Staple Singers of Chicago. Musicians recording and performing in Nashville were no doubt influenced by Memphis artists to the west and Chicago artists to the north, much as they were by Appalachian music to the east and the Delta Blues further south. Such geographic and cross-genre connections were on full display in 2019, when Mavis Staples celebrated her eightieth birthday with a concert at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, sharing the stage with country and soul singers. This guide explores the intersection of music, artists, and audiences with attention to the complexities of race relations in Nashville and in the South.

There is no doubt that Nashville has earned its musical acclaim. And yet, equating “Music City” with Nashville has functioned to overshadow musical hubs across Tennessee, most notably Memphis, home to Stax Records, one of the most influential soul music record labels in American history. The title of this guide — in addition to reflecting the participatory nature of this text — is a nod to the hit single by the same name. Recorded at Stax and written by Al Bell, originally of Little Rock and later co-owner of Stax, “I’ll Take You There” was made famous by the Staple Singers of Chicago. Musicians recording and performing in Nashville were no doubt influenced by Memphis artists to the west and Chicago artists to the north, much as they were by Appalachian music to the east and the Delta Blues further south. Such geographic and cross-genre connections were on full display in 2019, when Mavis Staples celebrated her eightieth birthday with a concert at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, sharing the stage with country and soul singers. This guide explores the intersection of music, artists, and audiences with attention to the complexities of race relations in Nashville and in the South.

[Read more about the book here.]

From the introduction to I’ll Take You There: Exploring Nashville’s Social Justice Sites, edited by Amie Thurber and Learotha Williams Jr., forthcoming from Vanderbilt University Press in May 2021. Copyright ©2021 Vanderbilt University Press. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Learotha Williams Jr. is a professor of African American, Civil War and Reconstruction, and Public History at Tennessee State University and coordinator of the North Nashville Heritage Project. Amie Thurber is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at Portland State University.