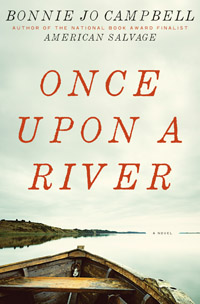

The River Rose

In Once Upon a River, Bonnie Jo Campbell introduces a fearless young heroine whose escape on the water brings her close to both danger and desperation, but also to courage

At age fourteen, a quiet and beautiful girl learns to shoot a rifle. A natural with the weapon, she feels “the guidance of the gun itself,” writes National Book Award finalist Bonnie Jo Campbell in Once Upon a River, her second novel. “It held her steady, and then sadness perfected her aim.”

Absorbing, exotic, and relentlessly heartbreaking, Once Upon a River follows the journey of young Margo Crane, who comes of age in the late 1970s on a river in Michigan. As a child, Margo loves the Stark River’s waters and silted banks, which she explores with a gaggle of boy cousins who live on the bank opposite her family’s home. But just as the Stark is fouled in the stretch where a metal fabricating plant releases its wastewater, all does not stay pure in Margo’s world for long.

Margo is abandoned by her mother, no fan of river life, who departs with a vague promise to return for her in the future. The following year brings the death of Margo’s grandfather, who calls her “Sprite” or “River Nymph” and nourishes her prowess in fishing and trapping. At a family gathering, the very uncle who first took her hunting rapes her in a tool shed. (“You’re so lovely,” he whispers to her. “It’s unholy.”) A year later, when she is sixteen, she watches as her eleven-year-old cousin shoots her father dead.

Alone, Margo turns for solace and security to the river she knows so well. “Instead of feeling trapped by the river, which might freeze her or drown her, she felt terribly, painfully free,” Campbell writes. “Without her father, she was bound to no one, and with the water flowing around her, she was absolutely alive.” Aboard The River Rose, the sturdy teak craft her grandpa bequeaths her, Margo paddles upstream, carrying with her little more than her rifle, her father’s old Carhartt jacket, and a book about her hero, the sharpshooter Annie Oakley, whose life bears more than a few resemblances to her own. She plans to make her way to her mother, who has hinted at her whereabouts in a letter that Margo finds among her father’s belongings.

Alone, Margo turns for solace and security to the river she knows so well. “Instead of feeling trapped by the river, which might freeze her or drown her, she felt terribly, painfully free,” Campbell writes. “Without her father, she was bound to no one, and with the water flowing around her, she was absolutely alive.” Aboard The River Rose, the sturdy teak craft her grandpa bequeaths her, Margo paddles upstream, carrying with her little more than her rifle, her father’s old Carhartt jacket, and a book about her hero, the sharpshooter Annie Oakley, whose life bears more than a few resemblances to her own. She plans to make her way to her mother, who has hinted at her whereabouts in a letter that Margo finds among her father’s belongings.

Between stretches of solitude—weeks and months spent fishing, hunting, and foraging— Margo takes up with a series of men, each one a contrast to the last. One wants to cage her; one wants to tame her; one wants to set her on a path back to school. Each meets her needs in real ways, offering her food and shelter, survival skills, and, not least, sexual companionship. (Desire, for Margo, offers “the same urgency she felt when she had a buck in her sights.”) In lieu of school—which she never enjoyed—young Margo has only the teachings of these men. All are, to some degree, replacements for both her lost father and grandfather. From them, she also learns tough lessons about protecting herself.

Campbell does not shy from the brutal details of Margo’s river existence. She matter-of-factly describes the steps involved in skinning and eviscerating a rabbit and muskrat, and she’s attentive to the way Margo cleans and cares for her rifle, keeping it near, always, as if it’s an extension of her body. And her depiction of female adolescence, of Margo’s confidence and pleasure in making her own way in the wild, is equally clear: “Fish and turtles and water birds were her family, she supposed, not humans, despite the comfort she might get from food and beds, from hot showers and lovemaking,” Campbell writes. “Even when she had lived in her father’s house, every morning in summer and winter the river had spoken more clearly to her than he had.” It is difficult to pity Margo, even as it is impossible not to fear for her in her isolation, her sheer youth, and the proximity of danger and desperation.

Campbell does not shy from the brutal details of Margo’s river existence. She matter-of-factly describes the steps involved in skinning and eviscerating a rabbit and muskrat, and she’s attentive to the way Margo cleans and cares for her rifle, keeping it near, always, as if it’s an extension of her body. And her depiction of female adolescence, of Margo’s confidence and pleasure in making her own way in the wild, is equally clear: “Fish and turtles and water birds were her family, she supposed, not humans, despite the comfort she might get from food and beds, from hot showers and lovemaking,” Campbell writes. “Even when she had lived in her father’s house, every morning in summer and winter the river had spoken more clearly to her than he had.” It is difficult to pity Margo, even as it is impossible not to fear for her in her isolation, her sheer youth, and the proximity of danger and desperation.

Ultimately, Margo’s travels up and downstream, and her experiences with men and boys along the way, show her grappling not only with the immediate tasks of survival but with the larger question of what sort of life she might make for herself back in the society she has fled. Always a silent kid, an outsider at school, she can’t look to her mother and father for answers. Only in her Aunt Joanna—a capable, hard-working woman whose loyalty and dedication to her family stand in stark contrast to Margo’s mother’s self-absorption—does she find much to admire. Even Joanna’s plain looks seem to kindle respect in Margo, although she does not grasp the challenges her own natural beauty can present. Even as she begins to accept that Joanna cannot be the mentor or protector she seeks, Margo follows in her aunt’s footsteps in the satisfaction she gains from doing for others. While she is not unhappy in her solitude, opportunities to nurture others clearly figure into her happiness.

A journey narrative always offers dramatic potential, the promise of a character’s transformation after she logs those hard, actual miles. Once Upon a River is a transcendent example of the form, a book with a singular, deeply complex protagonist who refuses to be contained or forgotten.

Bonnie Jo Campbell will read from Once Upon a River on February 9 at 7 p.m. in Buttrick Hall, Room 101, at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. The event is free and open to the public. For more details, click here.