The Stories We Tell

Through a nonlinear twinning of murders—one real and one imagined—Manuel Muñoz explores the way fiction is embedded in human lives

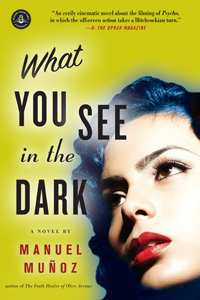

Manuel Muñoz’s first novel, What You See in the Dark, weaves together the stories of two murders, one “real”—that is, it actually takes place in the fictional world of the novel—and one fictional even within the novel’s imagined world. In 1950s Bakersfield, California, a young Latina shopgirl, Teresa Garza, is murdered, presumably by her lover Dan Watson, the town’s handsomest man, who disappears in the wake of her death. Around this time, a film crew comes to Bakersfield from Los Angeles, a few hours south, to scout locations for a film in production. That film, left unnamed in the novel, is Psycho, and Alfred Hitchcock and shower-scene star Janet Leigh appear in the narrative only as “The Director” and “The Actress.” The categorical titles are a nod to the novel’s central theme: the way role-playing is essential to our very existence. Though it is on one level a murder mystery, What You See in the Dark is also a quiet, slow-boiler of a book, driven more by ideas than by drama.

Through this nonlinear twinning of murders, Muñoz explores the way stories are embedded in lived experience, from the movies we consume and absorb, to the stories we tell ourselves about our lives, to the narratives we (mostly unwittingly) construct to make sense of strangers and intimates alike. With the turn of every page, he lays bare the constructed nature of reality—the multiplicity of constructions of any one event. “There is what you see and what you make of it, what you know for sure and what you have to experience, what others tell you and what gets confirmed,” he writes—and repeats, the narrative voice echoing itself—in the book’s first chapter, which channels the perspective of Candy, Teresa’s fellow shoe-shop employee.

The subtext, of course, is that none of this is wholly true or false. All “knowing” is inherently provisional, and the novel provides a masterful example of the power of multiple points of view to explore that fact. The perspective shifts between Candy and three other women—Teresa, The Actress, and Dan Watson’s mother, Arlene—all of whom are misunderstood by others, seen-but-not-seen. They are gazed upon by each other and by men, but they are never fully known.

The subtext, of course, is that none of this is wholly true or false. All “knowing” is inherently provisional, and the novel provides a masterful example of the power of multiple points of view to explore that fact. The perspective shifts between Candy and three other women—Teresa, The Actress, and Dan Watson’s mother, Arlene—all of whom are misunderstood by others, seen-but-not-seen. They are gazed upon by each other and by men, but they are never fully known.

Arlene, a widow and a longtime waitress at a Bakersfield café where Dan brings Teresa for lunch, is the eldest of these four central figures, and the least susceptible to illusion. When The Actress shows up at the café, Arlene muses that the younger girls who work there, all avid readers of Hollywood gossip rags, will construct fictions from that observed moment. “[T]hey would come up with a story, but it would be the wrong one…Here, people believed whatever story they wanted to believe,” she thinks. Arlene is a tragic figure, in some respects more tragic than the murdered Teresa, and painfully self-aware of the distance between her multifaceted vision of herself and the way the small community perceives her:

She was a waitress. She was a motel owner. She was a mother. She was an abandoned wife. She served coffee. She had a brother whom she had loved from a great distance, yet never saw again. Her name was Arlene. She served pie. Her name was Mrs. Watson. Her name was Arlene Watson before and during and after. She slid coins off countertops and dropped them into her apron pockets. She wanted to tell this to those girl waitresses to see if they would understand—that she was all of those things, and the town had a story about her and yet the story would never, ever come close to the truth. That she had a story and that it could change and that it was not over and that she was not on the last page…. Things change, she wanted to say. You don’t know anybody’s story.”

She was a waitress. She was a motel owner. She was a mother. She was an abandoned wife. She served coffee. She had a brother whom she had loved from a great distance, yet never saw again. Her name was Arlene. She served pie. Her name was Mrs. Watson. Her name was Arlene Watson before and during and after. She slid coins off countertops and dropped them into her apron pockets. She wanted to tell this to those girl waitresses to see if they would understand—that she was all of those things, and the town had a story about her and yet the story would never, ever come close to the truth. That she had a story and that it could change and that it was not over and that she was not on the last page…. Things change, she wanted to say. You don’t know anybody’s story.”

In the next chapter, Teresa echoes Arlene’s sentiment, having “learned quickly that people in Bakersfield had their own ideas about who she was and could be.” But at times she herself displays a false understanding of her own co-worker, Candy. Again and again, the book examines the distances between people, and the fictions, the unknowing, at the heart of everyday reality. The small-town folk of Bakersfield gaze upon one another with little more understanding than any out-of-towner might have of any one of them.

In fact, it is The Actress, emissary from that world, who shows more capacity for empathy than anyone else in the novel, the skills of her profession allowing her a measure of insight into the hearts and minds of Bakersfield’s residents. Having arrived at a Bakersfield hotel where she waits for The Director, she wonders “what it would be like to be a cleaning woman in a small hotel in an inconsequential city, the daily humdrum of that kind of life.”

Muñoz’s attention to language is keen, his sentences crafted with precision and a calculated deployment of repetition that sometimes calls to mind the trademark phrasings of Joan Didion. At every turn, he reminds us that this is a story about looking and being looked at, about what we know and what we don’t of others and our own selves. And with each consecutive chapter, each shift in perspective, the novel gracefully exposes the artifice that girds both the movies and the real world. Like the rest of the women in the novel, Teresa succumbs to the spell of the media when, on her lunch hour, she stands enchanted in front of an electronics-store window, where a bank of color TVs shows glamorous female singers. Later, the town’s eyes will watch her, hungrily, as she lunches with Dan behind the large, plate-glass windows of the café. Desire and curiosity fuel the looking, just as they do when The Actress stands on set beneath a showerhead that “look[s] down on her like a giant eye.” Some readers may feel that Muñoz wears his themes thin, reemphasizing them as he does via the motifs of eyes, windows, and stories. But the effect is also intoxicating, convincing, a prosecution of an idea through an almost hypnotic approach. Hitchcock would surely approve.

Manuel Muñoz will give a reading at Vanderbilt University in Nashville on March 15 at 7 p.m. Click here for details.