The Uses for Freedom

Robert Cheatham remembers his friend Reynolds Price—and their one public conversation about sex

Shortly after Reynolds Price’s death, Margaret Renkl, knowing he and I were longtime friends, asked if I would write something on Reynolds’ life and/or death for Chapter 16. Because I cannot say no to Margaret and saw it as a legitimate duty, I said I would. Off and on during these six months since, I have tried to think of what I could say. My problem is that I am being asked to write about Reynolds the public figure, the writer and teacher who belongs to us all, but my grief is private and personal, and seems meaningful only to me.

At least since the early 1970s, when I was in Chapel Hill, and Reynolds, understandably, had little patience with English graduate-school talk, we did not much discuss the whys, or even the content, of our work. He sent me all of his books, which I read and praised, but generally our talk was rarely about literature, even when it concerned the literati. Consequently, I have no particular insights into his accomplishments as an artist, or even as a teacher, though I first knew him as a teacher. His words spoke to me as much because of who I was, and am, as because of who he was, and I miss him for all the complex reasons that you miss anyone you loved who loved you back, who was a significant presence in your life for almost fifty years, and, not incidentally, whose passing reminds you that, too soon, death will come knocking on your door.

At least since the early 1970s, when I was in Chapel Hill, and Reynolds, understandably, had little patience with English graduate-school talk, we did not much discuss the whys, or even the content, of our work. He sent me all of his books, which I read and praised, but generally our talk was rarely about literature, even when it concerned the literati. Consequently, I have no particular insights into his accomplishments as an artist, or even as a teacher, though I first knew him as a teacher. His words spoke to me as much because of who I was, and am, as because of who he was, and I miss him for all the complex reasons that you miss anyone you loved who loved you back, who was a significant presence in your life for almost fifty years, and, not incidentally, whose passing reminds you that, too soon, death will come knocking on your door.

The part of our relationship that was public, that belonged to Reynolds’ life as a writer, was minimal. I introduced him once at the Southern Festival of Books. What I said then might be a good summation, and I remember that Reynolds was moved by my words. But I suspect my purpose was more to move Reynolds than to summarize his accomplishments. Whatever the case, the introduction is now lost. Reynolds dedicated his novel Blue Calhoun to me. That moved me, which was Reynolds’ purpose. Certainly, I am unaware of any way in which the story of my life would illuminate the novel, or vice versa, though I once spent half an hour on the phone with someone who was writing a paper and seemed convinced that I was being intentionally evasive about having run off with a teenaged girl.

Early in our friendship, when I was a VISTA volunteer on the Navajo Reservation, Reynolds visited me for a week over the Christmas holidays. Like that whole year, his visit was rich with unplanned adventure, some of which Reynolds transformed into a long story called “Walking Lessons.” The “social worker with his head up his ass six light years” is based on me. Most of the context, the scene-setting action, and the immediate internal conflicts of the characters of that story are pure fiction while the exterior action of the central episodes is mainly true. That distinction was confusing to my mother, who thought she had raised me better, and she had, than to have sex with the Navajo woman the fictional Dora is based on while Reynolds had to listen in the next room. It goes without saying that the Reynolds-like character is not really Reynolds either, and his wife did not kill herself.

Such adventure was not typical of our time together, particularly after Reynolds was confined to a wheelchair. Even before the chair, our friendship consisted mainly of conversation. The only public documentation of those conversations—albeit staged, intentionally one-sided, and less laughter-filled than usual—is an interview I conducted with Reynolds in 1991 for Humanities Tennessee’s former magazine, Touchstone. The subject of the issue was “censorship in the schools,” and I asked Reynolds for the interview because almost twenty years earlier I’d read Milton’s Areopagitica for his class and wanted to begin with that. I also knew that Reynolds would have, as always, plenty of interesting things to say in interesting ways, all of which I would likely agree with, and that he and I would be comfortable talking about sex.

Censorship, Literature, & Public Education

Born in Macon, North Carolina, in 1933, Reynolds Price received degrees from Duke University and Merton College, Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. Since 1958, Price has taught at Duke where he is now James B. Duke Professor of English.

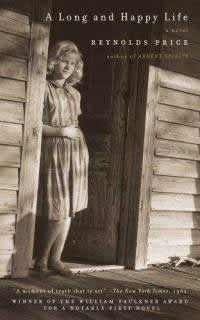

Price’s long and distinguished literary career has been remarkable both for his virtuosity and for the variety of forms he has embraced. In addition to eight novels—including his first, A Long and Happy Life, which received the William Faulkner award for a notable first novel and has never been out of print, and in 1986, Kate Vaiden, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award—Price has published three volumes of short stories, including his most recent book The Foreseeable Future, three volumes of poems, as well as plays, essays, translations from the Bible, and a memoir, Clear Pictures.

Price is a member of the National Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Robert Cheatham: In addition to writing novels, short stories, plays, poems, essays, and translating stories from the Bible, you have taught an enormously popular course on Milton for almost thirty years. In 1791, when our Bill of Rights became part of the Constitution, every educated person would have been familiar with Milton’s views on censorship as presented almost 150 years earlier in the Areopagitica. What were they?

Reynolds Price: Milton’s famous essay, Areopagitica, addresses itself, in fairly grandiose fashion, to the Parliament of England, and is a great plea for the absolute freedom of the press. It’s ironic that, as we now know, once Milton became an employee of Cromwell’s government, he himself was for a time a censor. His pure faith, presumably, in ordinary times was in an “absolute free public exchange of all conceivable information without any form of censorship.” The rational mind, he believed, should be given the privilege of making its own decisions.

Cheatham: Of course it is impossible to say, but given what you know about Milton, how do you think he would have responded to something like the Mapplethorpe photographs ?

Price: Well, we do know from his poetry, such as Paradise Lost, and from many of his prose works that Milton had an enormously healthy sense of the whole role of sexuality and of erotic love in the life of the human species, and of the dangers and excesses that are implicit in any force as powerful as eros. I strongly suspect—and maybe it’s only because I identify intensely with Milton in various positions—that he would have found some of the Mapplethorpe photographs so repellent as to be dangerous to exhibit. If we could imagine him alive in the 1990s, whether or not he would, in his office as a censor, have tried to prevent that exhibit, I couldn’t say.

Cheatham: In the Areopagitica, Milton is opposing the prevalent censorship of his time which was aimed at protecting particular religious or political interests. In America today, we can espouse in print almost any political or religious doctrine without any fear of censorship, but we tend to want to censor things that Milton does not seem at all concerned with. Was there in the seventeenth century anything like what we would recognize today as pornography?

Price: Oh, yes, definitely. Italy was the great source of what we might call pornography—literature that concerned itself with sex as mechanics, as opposed to sex as love. There were famous books with engravings of men and women engaged in all imaginable forms of intercourse. Certainly from Renaissance Italy on, we know that such things existed. And even earlier, throughout medieval Europe, we can find carvings in gothic cathedrals which would definitely be banned in Boston and Tennessee and North Carolina today, and certainly would not be found in our churches. And, of course, if you go to Pompeii, everybody tells you that you have to see the remaining pornographic frescoes in the old brothel. There’s nothing I know of to indicate that ancient peoples had anything like the problems we often have with such artistic or graphic displays of sexual behavior.

Price: Oh, yes, definitely. Italy was the great source of what we might call pornography—literature that concerned itself with sex as mechanics, as opposed to sex as love. There were famous books with engravings of men and women engaged in all imaginable forms of intercourse. Certainly from Renaissance Italy on, we know that such things existed. And even earlier, throughout medieval Europe, we can find carvings in gothic cathedrals which would definitely be banned in Boston and Tennessee and North Carolina today, and certainly would not be found in our churches. And, of course, if you go to Pompeii, everybody tells you that you have to see the remaining pornographic frescoes in the old brothel. There’s nothing I know of to indicate that ancient peoples had anything like the problems we often have with such artistic or graphic displays of sexual behavior.

Cheatham: So when did that become a problem?

Price: It would be too easy to say Victorian England. Of course, sexual neurosis and very distorted sexual behavior can be exhibited by primates in zoos, so it’s as old as primate life at least. But when the whole notion of pornography and censorship arose … we may have to conclude that it arose in Victorian England with bourgeois society. It’s hard to think that there was anything Shakespeare wanted to write about that he couldn’t write about. He’s full of all kinds of bawdry and what now, by a great many people, would be considered blatant obscenity, though it seems to have given the Elizabethan theatre and Queen Elizabeth and King James, who liked the plays, no trouble at all.

But what I know—just from observing older generations of my own family—is that one of the mechanisms of what we think of as Victorian prudery was that many of these people would say, and delight in and laugh about, a great many thoughts on the subject of sexuality, but they wouldn’t write them down. And that wasn’t so much because they felt that there was anything dirty about it. It simply was the convention; it was decorum. In our family, Grandmother sitting there in her little lace collar and cameo was perfectly capable of enjoying a bawdy joke, but it never would have crossed her mind to write one in a letter or to buy herself a joke book where she could read more such things.

Cheatham: Do you find in your own writing that you’re ever censoring yourself?

Price: I began publishing books in 1962, and my first novel contained a very graphic sexual scene, which I hope was described in language that was very clear and revealing and interesting and yet could not have been called pornographic in the sense of being obsessed with the mechanics of sex. I can’t think of being constrained by

myself or anyone else on the subject of sexuality in my work until maybe the last three or four years when the question has arisen of whether or not to describe certain kinds of sexual acts, such as homosexual acts or what might be thought of as promiscuous heterosexual acts. It’s very difficult to describe those now simply because the intelligent reader is now controlled by a sense of the awfulness of AIDS and the danger of AIDS, and I think that danger has introduced into our consciousness as writers certain kinds of calculations that we have to make—if character x does so-and-so, is the reader going to think that character x is criminally irresponsible by doing this with one character and then going and doing it with another character? But beyond that, I’ve never felt constrained; and I’ve certainly never been told by an editor or publisher that I couldn’t say certain things in my work.

Cheatham: But you, of course, write for adults who are free to read your work or not. The question of censorship in the schools, where we’re dealing with children and adolescents and required readings, is less clear. Where do you think those lines should be drawn? How does one decide, and who decides?

Cheatham: But you, of course, write for adults who are free to read your work or not. The question of censorship in the schools, where we’re dealing with children and adolescents and required readings, is less clear. Where do you think those lines should be drawn? How does one decide, and who decides?

Price: I’m not taking the position that absolutely everything that some human being might think up and get into print should be available to every other human being. That’s obviously a colossally complicated problem. I don’t see how, in a republic, those questions can ever satisfactorily be answered, simply because we are far too diverse a culture in terms of religious background, standards of child-rearing, and what a given family feels about a given child’s exposure to this or that. We have a public education system which is tax-supported; ergo those systems are subject to the will of the public—and sometimes to the bad whim of taxpayers who don’t know what they’re talking about. On the other hand, if I were a parent, and knew that some form of sado-masochistic photography involving pre-adolescent children were being purveyed in the art class in my public high school, I would be extremely vocal as a parent in saying that I thought this was highly inappropriate. Or at the very least, I would be engaged in a very careful attempt to be sure that my child had some sense of perspective about what relation these photographs bore to anything we might call love or human care or human sexual pleasure.

Obviously, I’m deeply concerned as a writer and as a reader when The Catcher in the Rye, one more time, is blacklisted by a local school board, when we know that the only thing wrong with The Catcher in the Rye is that the word f**k occurs there x number of times. And you realize that many of the parents who ask that it be censored have simply never known that their child says it far more frequently per hour than J.D. Salinger ever said it in print.

Cheatham: Touchstone is tax-supported, and I’m not sure we can risk printing that word even though we know children say it.

Price: You can disguise it with asterisks. … But I really don’t know how, in public schools, we do it any better than we do it. I teach in a private university. Throughout my thirty-three years of teaching, I have had no desire to shock my students for the sake of shock; but when any question has arisen in a given text about whether my students can handle what, for example, Hemingway might have to say, or his characters to show, about adultery, I have assumed that these people are here of their own free will, and if they don’t like it they can get up and walk out. I can’t think of any occasion on which a student has done so, or has ever even come to me and said, “I am disturbed by this passage in Faulkner about sexuality.” I have tried frequently to talk with my students through the years about matters of positive and negative love, about eros. But then again, I’m not teaching in a public school. Parents cannot come to me and say, “I am paying your salary. Shut up.”

Cheatham: But novels which the public schools have the most trouble with—such as The Catcher in the Rye and, more recently, the works of Judy Blume—are often the very ones that speak most directly to young people about a subject—sexuality—which is of intense interest to all adolescents.

Price: Yes. I read The Catcher in the Rye when it was brand new, either my last year in high school or my first year in college, and I was tremendously impressed by it as a fine book. But I’d read Hemingway and Tolstoy and Flaubert and was aware that human sexuality was dealt with in certain forms of serious literature. I would add what I think is a relevant fact. I graduated from high school in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1951, and I can say quite honestly that at the time I was not aware of knowing a male or female friend my age whom I was convinced had had full sexual relations with another person. And I don’t think that was at all unusual for me as a middle class American growing up in a small Southern city in the ‘40s and ‘50s. I’m sure there were such people, but I didn’t know them. I saw a lot of my friends and we talked and told dirty jokes and knew some people were bragging, but I couldn’t have said x has done it and y has done it.

Well, now—from what I hear my students say, from what I read in national surveys on sexuality, and from all the other information I have seen on the subject—any sane, middle-class parent would not be safe to assume that her teenage child had not had sexual relations and was not, possibly, having them on a very regular basis. That raises huge questions which run all the way from medicine and AIDS to philosophy and religion as to what texts we give this highly sexually active group of adolescents—and even pre-adolescents—to read and study. I would think it makes certain texts far more relevant, far more necessary, for them to read and have taught to them and expounded to them by teachers and parents in a responsible way. We’re faced right now with the incredible situation in which thousands of parents are violently objecting to having condoms mentioned as guards against AIDS in high-school sex education courses. Meanwhile, we know that AIDS is making deep inroads into the adolescent heterosexual population in this country.

Well, now—from what I hear my students say, from what I read in national surveys on sexuality, and from all the other information I have seen on the subject—any sane, middle-class parent would not be safe to assume that her teenage child had not had sexual relations and was not, possibly, having them on a very regular basis. That raises huge questions which run all the way from medicine and AIDS to philosophy and religion as to what texts we give this highly sexually active group of adolescents—and even pre-adolescents—to read and study. I would think it makes certain texts far more relevant, far more necessary, for them to read and have taught to them and expounded to them by teachers and parents in a responsible way. We’re faced right now with the incredible situation in which thousands of parents are violently objecting to having condoms mentioned as guards against AIDS in high-school sex education courses. Meanwhile, we know that AIDS is making deep inroads into the adolescent heterosexual population in this country.

But as a nation, we were settled by many non-conformist religious sects of Christianity; and we have always been faced with very heavy demands from various kinds of moralists—demands that I think one wouldn’t find made in a country like France or England. I’m not saying that this is necessarily bad, or that France and England are better countries, but just that they’re very different situations.

Cheatham: From what you know of history, what do you think is more typical of human behavior—the higher incidence of adolescent sexual activity today or the limited sexual experience of your high-school classmates in Raleigh?

Price: I have a feeling that if we could chart the sexual history of Homo sapiens, we would find that the sexual behavior of the European/American middle class was much more restrained from, let’s say, 1840 to 1960 than it ever has been before or since. I think we probably invented sexual repression with the rise of the middle class, for whatever reason.

Cheatham: And then around 1960, the so-called “sexual revolution” began.

Price: Yes, as I’ve said, I began publishing books in 1962, and the only time I’ve ever been aware of there being a parental protest about the reading of a book of mine came in about 1968 or 1969 when Agnes Scott College said that all the women who were entering as freshmen should read my second novel, A Generous Man. Some parent happened to read it and put up an almighty protest. I’ve forgotten how the matter was resolved, but I think that the book was withdrawn by the college as basic reading for all freshmen. My work is hardly sexually drenched, but certainly there is no novel of mine in which sexuality is not dealt with as candidly as I thought was necessary to tell the full story.

I would say that by the early ‘70s in America—more or less overnight with no big protest—we’d reached the point at which basically anything that a “serious” writer wanted to publish could be published without fear of any legal reprisal. It all started happening very fast with Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the Henry Miller novels. Grove Press cranked all that up from the early ‘60s on, and I think the beachhead was secure by the early ‘70s. That’s when Esquire asked me to write an essay about the fact that, more or less all of a sudden, novelists could say anything they wanted about sex in a novel. I said there that I think we can look back at certain classical novels and see that, for example, Thomas Hardy would have been better off if he could have talked more about sex in Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Tolstoy doesn’t need, however, in Anna Karenina to say one more word about sex than he says because it’s not a book about sex. To a large extent Tess is. Flaubert really did need to tell us more about how Emma Bovary responds once she starts having sex with these romantic-type men that she has been fantasizing about. Her illusory hopes destroy her.

When I wrote the article, I called it “The Uses for Freedom,” but Esquire called it “What Did Emma Bovary Do in Bed?”—which I must say is a better title than my own. If you’re going to really try to get down to what Madame Bovary is about, you do need to know more about her sexual behavior than Flaubert was able to tell you. And he got in legal trouble for telling you the little bit that he does.

Cheatham: Maybe the breakthrough was Peyton Place.

Price: Or Forever Amber or By Love Possessed. Oh, I remember distinctly when Gone with The Wind and The Grapes of Wrath were considered by my parents highly racy reading. And the books were huge bestsellers. There is an absolutely steady appetite for information about sexual behavior in the world’s population. We know that prudes and puritans have it as much as everybody else, often in far more exacerbated and maladjusted forms. Human beings, for whatever reasons, have some kind of innate need to know that other human beings have these needs and fulfill them in fairly similar ways. Sexuality is one of those realities that human beings do not wish to feel isolated in. When a society has any degree of sexual repression—and of course we still do—there is a deep curiosity to know: (a) that other people do this, that I’m not the only person who does this or feels this way; and (b) how do they do it?

Price: Or Forever Amber or By Love Possessed. Oh, I remember distinctly when Gone with The Wind and The Grapes of Wrath were considered by my parents highly racy reading. And the books were huge bestsellers. There is an absolutely steady appetite for information about sexual behavior in the world’s population. We know that prudes and puritans have it as much as everybody else, often in far more exacerbated and maladjusted forms. Human beings, for whatever reasons, have some kind of innate need to know that other human beings have these needs and fulfill them in fairly similar ways. Sexuality is one of those realities that human beings do not wish to feel isolated in. When a society has any degree of sexual repression—and of course we still do—there is a deep curiosity to know: (a) that other people do this, that I’m not the only person who does this or feels this way; and (b) how do they do it?

Far from wanting to edit out all explicit sexual information from the educational process in this country, I think that ideally speaking it would be very beneficial if most young Americans read a good deal more in good literature about sexual behavior than they do. I think I might have benefited a lot as a puzzled twelve or thirteen-year-old if I could have read some novel in which sexuality were dealt with in a very healthy, honest way. Those novels basically didn’t exist, or certainly weren’t available in North Carolina when I was that age. I understand now that, in what are called young-adult books, there is a good deal more about it; and I think that’s fine.

Again, I don’t know which ones of these books you select as part of your curriculum in a public high school and which ones you don’t. I suppose that we inevitably fall back on what’s called community standards, which really only means the standards of whatever person shouts the loudest and intimidates the hardest. Paradoxically, given the practical degree of more or less total sexual sophistication, or experience, that exists among young people today, we’ve become considerably more denying and prudish about admitting to ourselves that these people are doing it and need all the help they can get in doing it—that is, in becoming emotionally healthy adult human beings, which for most people means sexually functioning.