Unreasonable Schemes

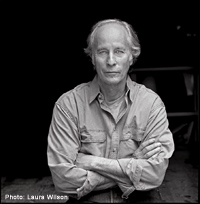

With Canada, Richard Ford returns to the bleak, forbidding landscapes of the Northwest and the thwarted lives of those who inhabit them

”At the heart of schemes like this, there’s always something unreasonable,” muses Dell Parsons, the stoic, haunted narrator of Richard Ford’s new novel, Canada. “The explanation for which,” Dell concludes, “is that human beings are involved.” The scheme to which Dell refers is his parents’ decision to stage a bank hold-up in a neighboring town near their home of Great Falls, Montana—a senseless, reckless choice that sends Dell’s life careening helplessly down a path that will lead him across physical and psychological borders that he will spend the rest of his life struggling to resolve.

In the years since the publication of Independence Day (1995)—the first novel ever to win both the PEN/Faulkner Award and the Pulitzer Prize—Richard Ford has achieved rare and lofty status as a cherished American institution, regarded mostly as a gifted chronicler of fin-de-siècle suburban angst in the tradition of Cheever, Updike, Richard Yates, and Ford’s fellow Mississippian Walker Percy. Ford’s reputation rests largely on the critical and popular acclaim of Independence Day and its two companion novels, The Sportswriter (1986) and The Lay of the Land (2007), a trilogy depicting the existential quest of Frank Bascombe—sportswriter turned real estate agent—as he navigates the twin obstacles of “whacking loss” and “the possibility of terrible, searing regret.” Bascombe’s erudite, metaphysical musings—at once tragic and whimsical—captured the zeitgeist of the age and established Ford as an enduring voice of educated, upper-middle-class malaise at the end of the American Century and the beginning of whatever lies before us.

Ford’s association with Frank Bascombe—as intimate as John Updike’s with Rabbit Angstrom or Philip Roth’s with Nathan Zuckerman—obscures the fact that his career is divided between the relatively urbane world of a philosophical writer-turned-realtor and the downtrodden, blue-collar, lawless, hardscrabble world most often associated with the late Raymond Carver, a dear friend of Ford’s from their early years as unknown writers scraping by on the workshop circuit. Great Falls, the quintessential volume of this half of Ford’s oeuvre, presents a cast of scarred and desperate characters in the blasted, frozen landscapes of the great Northwest. Frank Bascombe’s essential, quixotic faith in the goodness of life is nowhere to be found in the Montana of Great Falls. “It is just low-life,” Ford writes at the conclusion of the title story in the collection, “some coldness in us all, some helplessness that causes us to misunderstand life when it is pure and plain, makes our existence seem like a border between two nothings, and makes us no more or less than animals who meet on the road—watchful, unforgiving, without patience or desire.”

Ford’s association with Frank Bascombe—as intimate as John Updike’s with Rabbit Angstrom or Philip Roth’s with Nathan Zuckerman—obscures the fact that his career is divided between the relatively urbane world of a philosophical writer-turned-realtor and the downtrodden, blue-collar, lawless, hardscrabble world most often associated with the late Raymond Carver, a dear friend of Ford’s from their early years as unknown writers scraping by on the workshop circuit. Great Falls, the quintessential volume of this half of Ford’s oeuvre, presents a cast of scarred and desperate characters in the blasted, frozen landscapes of the great Northwest. Frank Bascombe’s essential, quixotic faith in the goodness of life is nowhere to be found in the Montana of Great Falls. “It is just low-life,” Ford writes at the conclusion of the title story in the collection, “some coldness in us all, some helplessness that causes us to misunderstand life when it is pure and plain, makes our existence seem like a border between two nothings, and makes us no more or less than animals who meet on the road—watchful, unforgiving, without patience or desire.”

The gap between these two worlds has long made Ford, as Lorrie Moore recently observed in The New Yorker, “an embodiment of interesting and intimidating contradictions” and “a writer of jangling personal fascination to many in the literary world.” With Canada, Ford seems to resolve some of these contradictions, intentionally or not, by placing a somewhat Bascombe-ish narrator—a retired English teacher named Dell Parsons—in the cold, bewildering, and unforgiving world of Great Falls.

“Our parents were the least likely two people in the world to rob a bank,” Dell recalls, drawing his memory back to 1960, when, as a boy just entering adolescence, he watched his parents careen helplessly toward a catastrophe that would land them both in prison and cast their children—Dell and his twin sister, Berner—to the wind. “A sociologist of those times—the beginning of the ‘60s—might say our parents were in the vanguard of a historical moment, were among the first who transgressed society’s boundaries, embraced rebellion, believed in credos requiring ratification through self-destruction,” Dell reflects. “But they weren’t. They weren’t reckless people in the vanguard of anything. They were, as I said, regular people tricked by circumstance and bad instincts, along with bad luck, to venture outside boundaries they knew to be right, and then found themselves unable to go back.”

Despite the terse suggestions of its title, Canada itself is not reached by Dell until the novel’s second half. Its first setting—its elegiac heart—is Montana—the home of that “low-life coldness” that haunts the pages of Ford’s best short fiction and his underappreciated fourth novel, Wildlife (1990), which is also set in 1960 and features an adolescent narrator observing his family on the verge of collapse. The Parsons family is not from Great Falls—they have relocated there, thanks to Dell’s father’s career with the Air Force.

The Parsons appear, from the outset, mismatched and adrift. Dell’s father, Bev, is a Southern charmer whose “graceful obliging manners should’ve taken him far in the Air force, but didn’t.” His mother, Neeva, the daughter of Jewish immigrants, who “featured herself possibly as a bohemian and a poet, and had hoped someday to land a job as a studious, small-college instructor,” has ended up married to Dell’s father for the expected reason. Neeva, who makes no secret of her despair to her twin children, frequently must have considered leaving Bev, Dell reflects. But in Richard Ford’s Montana, there are no easy escapes.

The Parsons appear, from the outset, mismatched and adrift. Dell’s father, Bev, is a Southern charmer whose “graceful obliging manners should’ve taken him far in the Air force, but didn’t.” His mother, Neeva, the daughter of Jewish immigrants, who “featured herself possibly as a bohemian and a poet, and had hoped someday to land a job as a studious, small-college instructor,” has ended up married to Dell’s father for the expected reason. Neeva, who makes no secret of her despair to her twin children, frequently must have considered leaving Bev, Dell reflects. But in Richard Ford’s Montana, there are no easy escapes.

Nevertheless, Dell’s nostalgia is tinged with a far greater measure of generosity than condemnation or regret. “It seems possible, I suppose, to look back at our small family as being doomed, as waiting to sink below the churning waves, and being destined for corruption and failure,” Dell explains. “But I cannot truly portray us that way, or the time as a bad or unhappy time, in spite of it being far out of the ordinary.” Dell preoccupies himself with his interest in beekeeping and a burgeoning obsession with chess, which he hopes will help him find friends in high school. Berner grows into a sullen girl “who was now skeptical with life” and “angry”—observations that reveal Dell’s persistent optimism, in spite of everything.

The foolishly self-destructive part of the story is preceded by something more mundane. Bev Parsons involves himself in a small-time scam with a group of Cree Indians who butcher rustled cattle and use Bev to sell the contraband. A conflict over a spoiled shipment leaves Bev in the lurch. Facing threats of violence, Bev gamely decides to solve his problems by turning himself and Neeva into Bonnie and Clyde. The children are left to their own devices. They spend a strange and chilling night alone, and then Berner disappears, not to be seen again for fifty years.

The novel’s second half takes Dell, finally, to Canada, where, in a misbegotten effort to save him from being swallowed up by state social services, Neeva’s closest friend whisks him across the border into Saskatchewan. There, Dell becomes the ward of another lethally charming rake, Arthur Remlinger, who has fled the United States for unknown crimes and established himself as a hotelier in Fort Royal. Dell’s primary companion, a cross-dressing part-Indian called Charley Quarters, introduces Dell to the barren, isolated, and violent world that will shape his adult consciousness. Dell’s patient narration of his lodgings—he lives in a cluttered Quonset hut in a meadow a short distance away from Port Royal—reflect both his scientific, inquisitive nature and his unspeakably sorrowful loneliness. His primary tasks are to clean hotel rooms and, along with Charley Quarters, to gut and de-feather the geese killed by the so-called “sports” who make up most of Arthur Remlinger’s business. This filthy, bloody work, along with the vaguely sinister Arthur Remlinger, make it clear that Dell is being drawn against his will toward yet another violent and life-altering confrontation.

What results is predictable: Arthur Remlinger’s past comes back to haunt him, and Dell unwillingly becomes implicated in an even more senseless crime. But suspense really isn’t the point of this or any of Ford’s novels. We learn in the first paragraph what will become of Bev and Neeva, and, implicitly, what it will mean for Dell and Berner. The tension in Canada derives entirely from the adult consciousness of Dell Parsons as he struggles to make sense of what happens to the two of them as a result of their parents’ disastrous choices. Dell wants to understand, but he also wants to love, and to forgive. He can’t dismiss either or both of his parents the way they were characterized in the Montana papers, or the way they would be depicted today on 24-hour cable news.

“I could like it or hate it,” Dell remarks, “but the world would change around me no matter how I felt.” Nevertheless, he refuses to dismiss his tragic childhood as meaningless misfortune. Unlike Jackie, the young narrator of “Great Falls,” Dell Parsons cannot see anything as “pure and plain.” Like Frank Bascombe, Dell wants to believe that the world can be comprehended, in all of its complexity. Ford seems to be suggesting, in the fusion of the desperate and hopeful strains of his work, that some reckoning can be made of life’s cruelty and randomness. In this regard, Canada recalls the philosophy of one Ford’s great influences, Walker Percy: “I take it as going without saying that the entire enterprise of literature is like that of a physician undertaken in hope,” Percy once wrote. “Otherwise, why would we be here?”

Richard Ford will discuss Canada at the Nashville Public Library on June 14. The event is part of the Salon@615 series and will begin with a reception at 6:15 p.m. Both the reception and the reading are free and open to the public.