We Are Not in the Zone of Logic

Padgett Powell exercises free imaginative play in the absurd stories of Cries for Help, Various

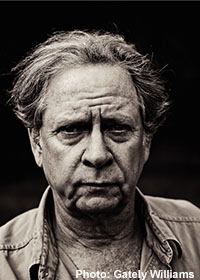

At the 2013 Southern Festival of Books, Padgett Powell was asked if he intended his novel You & Me to be an homage to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Though that comparison was made by many reviewers (and though the cover of You & Me features two Beckettian characters wearing top hats), Powell found the notion laughable. “When I’m writing, my window is about six characters wide,” he explained. With such intense concentration on language, Powell leaves larger questions of literary form and influence for critics to debate. All he cares about is the next sentence.

Powell, a creative-writing professor at the University of Florida, tells students that a writer’s top two mandates are to “be alive” and “be surprising.” In six novels and two previous collections of stories, he has modelled those dicta with verve and spirit. In You & Me and The Interrogative Mood, a short novel consisting entirely of unanswered questions, Powell rejects naturalistic conventions like character and plot in favor of language that makes a direct connection with the reader. With his new collection of short fiction, Cries for Help, Various, he continues in this vein, providing a lively medley of voices that sound off on his own pet themes.

Powell, a creative-writing professor at the University of Florida, tells students that a writer’s top two mandates are to “be alive” and “be surprising.” In six novels and two previous collections of stories, he has modelled those dicta with verve and spirit. In You & Me and The Interrogative Mood, a short novel consisting entirely of unanswered questions, Powell rejects naturalistic conventions like character and plot in favor of language that makes a direct connection with the reader. With his new collection of short fiction, Cries for Help, Various, he continues in this vein, providing a lively medley of voices that sound off on his own pet themes.

Occasionally Powell lays bare his process of creation, stopping mid-tale and commenting on its direction. In “Hoping Weakly,” he writes, “I hope for something. It is not a strong hope. The strength of the hope does not exceed—I am now seeing lightning out the window—let me restart the sentence. The weak hope I have is congruent to the weak vision I have of whatever it is I hope for. I hope weakly and vaguely.” These interruptions convince readers that they are following a live performance as Powell’s six-character window scrolls past. “We are not in the zone of logic,” one narrator puts it, mildly. “If you do not already divine what I am talking about, there’s nothing for it, no explaining this.”

The figures who populate Powell’s fiction often resemble the author’s own profile—nearing sixty, literate, living in the South. When Powell expands his scope, he tends to drift down the socio-economic ladder to hard-up men who retain a sense of dignity. He identifies his target population in “Horses,” the new collection’s first piece: “We are the ungainfully employed, unjailed, unlettered, unprotected fair boys left in the world.”

A tone of stoic acceptance permeates Cries for Help, Various. Powell’s characters have seen enough to know that they don’t have to strive for greatness to be struck down by fate. The “bright, challenging world” crushes the humble, too: “It seems to me that if you do not deign, presume, and meddle, though, that the forces of the world at large, sometimes in the form of a kind of anonymous aggregate power, will pile up on you in an ambient deigning and presuming and meddling that will render you helpless,” he writes.

“The Imperative Mood,” the collection’s finest piece, contains disconnected jets from the author’s fountain of wisdom. Some lines re-contextualize old nuggets: “Test the wind. Brave the currents.” Some urge acceptance of aging: “Do not lament the loss of testosterone.” Many recommend ways to avoid calcification, both mental and physical: “Alternate the theories you entertain about all things. Investigate leather tanning. Learn to swim again.” Here and elsewhere Powell reveals his own literary kinships: “Inspect the phrase ‘resistant incoherence’ as it pertains to John Ashbery, whose incoherence you have not so much resisted as found incoherently beautiful.”

“The Imperative Mood,” the collection’s finest piece, contains disconnected jets from the author’s fountain of wisdom. Some lines re-contextualize old nuggets: “Test the wind. Brave the currents.” Some urge acceptance of aging: “Do not lament the loss of testosterone.” Many recommend ways to avoid calcification, both mental and physical: “Alternate the theories you entertain about all things. Investigate leather tanning. Learn to swim again.” Here and elsewhere Powell reveals his own literary kinships: “Inspect the phrase ‘resistant incoherence’ as it pertains to John Ashbery, whose incoherence you have not so much resisted as found incoherently beautiful.”

This collection displays a fascination with women (“Goddamn that is a cute girl out there on the street,” Powell writes in “The Indicative Mood”), tempered by reminders that, generally speaking, women should be left alone. His “imperatives” include: “Do not oppress any of the women you have already oppressed, and try not to oppress any new ones. Try to get all the way to the grave, in fact, without oppressing another woman.”

Several of the stories in Cries for Help, Various involve middle-aged men who are starting over. A couple of Powell’s narrators face the predicament of recreating their existences after divorce. “The New World,” the most moving divorce story, features a man who, however daunting the future appears, knows better than to blame his plight on others. “It is, a divorce, not unlike bringing a meal along slowly and then through neglect burning this dish or that, and then perhaps another, and ultimately facing the situation, after long work, of an inedible repast, guests milling around unsatisfied and ready to head out for fast food,” the narrator says. “All that was needed was an ounce or two more of circumspection and caution and witness. The vision of that meal will linger.”

Though none of Powell’s recent fictions satisfy the expectations of orthodox storytelling, some of the pieces in this collection manage to offer a semi-coherent sketch of an elliptically drawn character as he endures a partially recognizable life-phase. Other pieces read as unadulterated linguistic play by an author allowing his imagination free rein. Taken together, the short compositions assembled in Cries for Help, Various portray a consciousness wearied by experience but on the lookout for objects of wonder. More than anything, they reveal an author who wants to use language to revivify the world.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford University as an undergraduate. He later returned to Austin, where he earned a Ph.D. in modern fiction from the University of Texas. He now lives in Nashville.