What Is Left

A dime-store scrapbook preserves priceless seventy-year-old memories

As scrapbooks go, it is small. Thirty-two cheap paper leaves, each 8 ½ by 12 inches, creating sixty-four pages on which to paste whatever memories the owner wanted preserved. The cover, of only a slightly better grade of paper than the leaves, bears a printed scene titled “Winter Wonderland” that portrays dormant trees, a frozen stream, and snow-covered buildings with warm, glowing windows. It is an incongruous cover, for the book’s contents, announced in three neatly handwritten lines at top center, are “Bruce and Pat, Our Honeymoon, Aug. 1947.”

Mom kept scrapbooks long before the recent commercialized, accessorized craze. She began in her youth in the 1930s. Her subjects ranged from personal memories to current events to movie stars. (Her favorites were Errol Flynn and Clark Gable.) I have two—the honeymoon and an earlier collection of newspaper clippings about World War II. As interesting as it is to read what the Detroit papers had to say about Pearl Harbor, my favorite is the smaller, honeymoon volume.

Mom kept scrapbooks long before the recent commercialized, accessorized craze. She began in her youth in the 1930s. Her subjects ranged from personal memories to current events to movie stars. (Her favorites were Errol Flynn and Clark Gable.) I have two—the honeymoon and an earlier collection of newspaper clippings about World War II. As interesting as it is to read what the Detroit papers had to say about Pearl Harbor, my favorite is the smaller, honeymoon volume.

They met, my mother and father, in 1946, at East Grand Boulevard Methodist Church. As a reserve officer in the Army Air Forces, Dad was still wearing his uniform, and Mom wanted to know who the handsome captain was. Before long, she had dumped her boyfriend and accepted Dad’s proposal.

They were married August 2, 1947, in the church where they met. She was recovering from mono, had lost a lot of weight, and her doctor urged a postponement. He misjudged her. My mother was a very determined woman, and there would be no putting off what she so strongly desired. Based on what she told me, the photos, and the newspaper clipping I still have, it was a large, traditional wedding. The honeymoon began that very day, as they drove west from the city in a 1946 Ford.

“Stayed here on our wedding night,” is the first entry in the scrapbook. Accompanying her text is a linen-paper postcard of the Hayes Hotel in Jackson, Michigan. A seven-story edifice topped by an American flag, the Hayes looks like a solid, respectable establishment in which to spend a wedding night. I have looked it up on the Internet and found that it still exists, currently undergoing renovation and soon to be reopened. In fact, I have used my mother’s scrapbook and the Internet to trace the route they took across the country that August. They spent the entire month driving to California and back, a lengthy journey even today, and a grand expedition in the 1940s, before the wide availability of air conditioning and the franchising of America.

“Stayed here on our wedding night,” is the first entry in the scrapbook. Accompanying her text is a linen-paper postcard of the Hayes Hotel in Jackson, Michigan. A seven-story edifice topped by an American flag, the Hayes looks like a solid, respectable establishment in which to spend a wedding night. I have looked it up on the Internet and found that it still exists, currently undergoing renovation and soon to be reopened. In fact, I have used my mother’s scrapbook and the Internet to trace the route they took across the country that August. They spent the entire month driving to California and back, a lengthy journey even today, and a grand expedition in the 1940s, before the wide availability of air conditioning and the franchising of America.

The book provides an almost day-by-day account, though the text is limited to simple labels, and Mom stopped numbering the days where the California section begins. I know they spent their third night in the Tower Tourist Village in Omaha, Nebraska, and that their fifth night’s rest was at the Ranger Motel in Laramie, Wyoming. The Ranger still exists, at 453 North 3rd Street, though it no longer appears to be the kind of place a newly married woman would choose to stay.

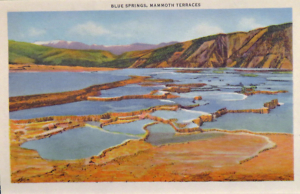

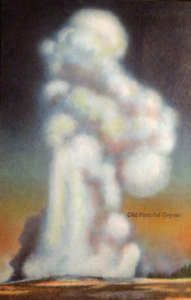

Most of the scrapbook’s contents are postcards, including an accordion-style color foldout set showing the geysers and hot springs of Yellowstone National Park, and two glossy black-and-whites of an empty Hollywood Bowl. But there are also restaurant menus—Alioto’s in San Francisco, still extant, served pan-fried fresh swordfish steak for $1.25—and business cards, like that from Packard’s Chaparral Trading Post in Santa Fe. I don’t know what they purchased at Packard’s, if anything, but the card carried with it some important piece of Mom’s memories of that trip.

Although the scrapbook provides a remarkably detailed record of the sights, and even tastes, of their first journey together, there are really only two uniquely personal items in the collection. One is a scorecard from Tropical Golf Gardens, a miniature golf course once located on El Cajon Boulevard in San Diego on property that is now part of a freeway interchange. Mom lost the game, thirty-five strokes to thirty-two. She beat Dad on two holes, but triple-bogeyed the fourth, putting her in a deficit she could not overcome. (Having played much mini golf with my Mom, I believe it is unlikely she threw the game as a concession to her new husband.)

Although the scrapbook provides a remarkably detailed record of the sights, and even tastes, of their first journey together, there are really only two uniquely personal items in the collection. One is a scorecard from Tropical Golf Gardens, a miniature golf course once located on El Cajon Boulevard in San Diego on property that is now part of a freeway interchange. Mom lost the game, thirty-five strokes to thirty-two. She beat Dad on two holes, but triple-bogeyed the fourth, putting her in a deficit she could not overcome. (Having played much mini golf with my Mom, I believe it is unlikely she threw the game as a concession to her new husband.)

The other personal artifact in the scrapbook is a matching pair of photographs, one of each of them, labeled simply “Pat” and “Bruce.” Mom is wearing a patterned skirt, white blouse, and a sweater draped over her shoulders. Dad is wearing light-colored slacks, sandals (with socks), and a pure white T-shirt. From the backgrounds I can tell that the photos were taken on Temple Square in Salt Lake City—Mom is standing in front of the Temple, Dad in front of the Tabernacle.

Whether the photos were taken by them or by a commercial photographer plying the tourists is unknown, but it is unlikely they took them. I know this for the same reason that I understand why there are no other personal photos in the honeymoon collection, the reason Mom had to rely on postcards, menus, and business cards to aid her memory. Mom didn’t take pictures in those days, and Dad was very handy with both still and motion photography, so it was his responsibility to document the adventure. His movie camera, the one with which he’d recorded so many North African scenes during the war, was his tool of choice for the first vacation with his bride. The reels of color film from that trip, including Yellowstone, Yosemite, San Francisco, San Diego, the Grand Canyon, Santa Fe, and more, were dutifully submitted to a film lab when they arrived home in Detroit. The lab ruined them. All of them.

Whether the photos were taken by them or by a commercial photographer plying the tourists is unknown, but it is unlikely they took them. I know this for the same reason that I understand why there are no other personal photos in the honeymoon collection, the reason Mom had to rely on postcards, menus, and business cards to aid her memory. Mom didn’t take pictures in those days, and Dad was very handy with both still and motion photography, so it was his responsibility to document the adventure. His movie camera, the one with which he’d recorded so many North African scenes during the war, was his tool of choice for the first vacation with his bride. The reels of color film from that trip, including Yellowstone, Yosemite, San Francisco, San Diego, the Grand Canyon, Santa Fe, and more, were dutifully submitted to a film lab when they arrived home in Detroit. The lab ruined them. All of them.

The two small, black-and-white photos taken on Temple Square are the only surviving images of my parents during one of the defining events of their lives. Mom preserved them along with whatever other souvenirs she could pull together, glued carefully into a dime-store scrapbook. A precious book, despite its humble origins, it was kept in a chest at the foot of their bed with other one-of-a-kind mementos of a long and rewarding life. That is where my sister, brother, and I found it when it was time to clean out the house.

Mom did not die a good death. There was no fairy-tale ending. Alzheimer’s took her mind. A C. diff infection took the rest. It was not quick. It was not painless. She did not make much sense even in the more lucid moments of the final days. But there were times when she mentioned people from her past. Dementia takes the recent memories first, so the old ones may have been left—images of long-ago days that could push through the morphine fog and let her be her again.

That is what I hope. That somewhere inside it was still August 1947, and the Hayes Hotel was still a solid, respectable establishment in which to spend a wedding night.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than twenty-five years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and a historian by avocation.