What Lies Within

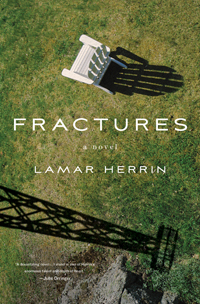

Lamar Herrin’s new novel considers environmental risk against a background of family strife

In Fractures by University of Tennessee graduate Lamar Herrin, Frank Joyner feels the weight of the world on his shoulders. Natural-gas drilling, known as “hydrofracturing,” has come to his small town, and many of his neighbors have already made deals to allow drilling on their land. Frank is a retired architect who specialized in re-purposing buildings that had outlived their original use. Whenever asked why his career had taken this direction, “he tended to fall back on ready-made phrases,” Herrin writes. “It was better to preserve than repair, better to repair than to restore, better to restore than reconstruct. In truth, there was an art to keeping things alive, to holding off collapse; instead of creating something out of nothing, to arresting the fall of something into nothing, of inverting the hourglass, as it were, when the last grains of sand were about to trickle through.” Now Frank feels responsible for holding off the collapse of his community’s way of life and preventing the desecration of his own family’s inheritance.

But Frank’s family home sits atop a vast natural resource and, potentially, a vast sum of money to be made from the leasing of his grandmother’s land for drilling. Frank is divorced, with three adult children: Gerald, the oldest, who fled the family for a quiet, comfortable life in California; Jen, restless in love and prone to wandering, and now a single mother to eleven-year-old Danny; and the troubled Mickey, a gifted man of unrealized potential who struggles to find meaning in life. Frank is torn between his duty to his family, including his two sisters and their children, who also look to benefit from any proceeds realized from the property, and his desire to protect the integrity of the natural world he cherishes, where he feels most at home.

But Frank’s family home sits atop a vast natural resource and, potentially, a vast sum of money to be made from the leasing of his grandmother’s land for drilling. Frank is divorced, with three adult children: Gerald, the oldest, who fled the family for a quiet, comfortable life in California; Jen, restless in love and prone to wandering, and now a single mother to eleven-year-old Danny; and the troubled Mickey, a gifted man of unrealized potential who struggles to find meaning in life. Frank is torn between his duty to his family, including his two sisters and their children, who also look to benefit from any proceeds realized from the property, and his desire to protect the integrity of the natural world he cherishes, where he feels most at home.

Mickey is skeptical of the promises made by the gas companies and advises Frank not to cooperate with them, citing the environmental damage that will almost certainly result from drilling. “Radium, strontium, barium, all radioactive,” he tells Frank, “plus whatever ‘lubricating’ chemicals the gas companies are putting in themselves. Surely benzene, for starters. Slickwater, they call it. Ninety percent of what they pump down there comes back up, and they call that flowback fluid. Thanks to Bush and Cheney and that crowd, utterly unregulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act.”

On the other hand, as Mickey also acknowledges, contamination is likely unavoidable since drilling is already scheduled to take place on adjoining properties: “Down went the drill, as far as two miles, he’d been told, and then out went the drill, and although the vertical drilling might take place on Farmer X’s property, the horizontal drilling could easily pass under yours. Hence, you were integrated. Legally. Compulsorily. The only difference was that Farmer X got paid.”

On the other hand, as Mickey also acknowledges, contamination is likely unavoidable since drilling is already scheduled to take place on adjoining properties: “Down went the drill, as far as two miles, he’d been told, and then out went the drill, and although the vertical drilling might take place on Farmer X’s property, the horizontal drilling could easily pass under yours. Hence, you were integrated. Legally. Compulsorily. The only difference was that Farmer X got paid.”

When a boy and his dog are hit by a gas company truck, the tension in the community, and in the family, worsens. “No one disputed that natural gas was a desirable transitional fuel, only half as polluting as oil or coal, or that the country possessed it in abundance,” Herrin writes. “The question was the price.” As Frank continues to weigh the cost, New York City attorney Wilson Michaels, the ex-husband of Frank’s sister, Carol, decides to stack the deck in his daughter’s (and his own) financial favor and gives Frank’s name to a gas-company “landman” named Kenny Brewster, a former drill-rig roughneck from Texarkana.

In Frank, the fatherless Kenny finds a man of deep principles whom he comes to admire and respect, while Frank immediately trusts the young man’s passionate belief in the importance of the drilling and the possibility of a future in which the land is restored and all parties benefit. But as Kenny’s fortunes rise both personally and professionally, Mickey’s begin to fall, and Jen, who loves both men, is caught in the middle. No matter what Frank chooses, he knows his decision will have repercussions that last for years, if not for generations. In Fractures, Lamar Herrin plumbs the fissures of a family, as well as of the land, and portrays the potential for reward and disaster that lies within both.