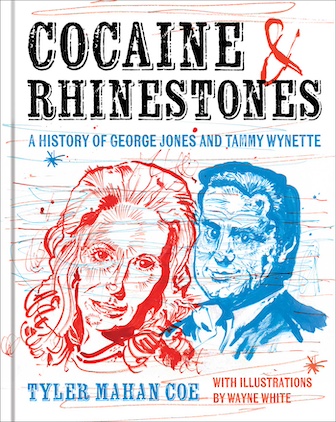

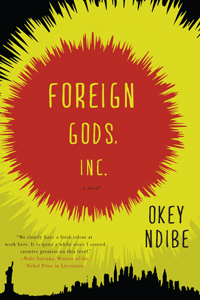

Whose God Will Prevail?

In Okey Ndibe’s Foreign Gods, Inc., African deities become pawns in the global market

Ikechuka Uzonda, the protagonist of Okey Ndibe’s Foreign Gods, Inc., faces problems everywhere he turns. A Nigerian who won a scholarship to Amherst, Ike’s accent has barred him from entering the American corporate world. For thirteen years he has worked as a cab driver in New York, but the money he earns is quickly exhausted by his dual addictions to alcohol and gambling, leaving nothing to send home to his African family. His flamboyant American wife has left him for a store owner with more ready money, and his landlord clamors for rent.

But Ike (pronounced “Ee-keh”) has hatched a scheme to solve his financial crisis. He has learned about a Manhattan gallery, Foreign Gods, Inc., where statues of Third World deities are selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Ike figures that his village’s war god, Ngene, who once led their warriors to triumph over every foe in the region, should be worth a premium to Western millionaires. He plans to fly back to Nigeria, steal Ngene, and capitalize on the current fascination with tribal religions.

But Ike (pronounced “Ee-keh”) has hatched a scheme to solve his financial crisis. He has learned about a Manhattan gallery, Foreign Gods, Inc., where statues of Third World deities are selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Ike figures that his village’s war god, Ngene, who once led their warriors to triumph over every foe in the region, should be worth a premium to Western millionaires. He plans to fly back to Nigeria, steal Ngene, and capitalize on the current fascination with tribal religions.

Ike understands that he will be ransacking his tribe’s traditions in the service of rapacious capitalism, but dire circumstances have pushed him toward this unpleasant expedient. He justifies his plan by quoting the words of the Foreign Gods gallery owner, who announces that religious icons must re-locate in order to remain potent: “In a postmodern world, even gods and sacred objects must travel or lose their vitality; any deity that remained stuck in its place and original purpose would soon become moribund,” he says. Ike knows that this “mumbo jumbo” is nothing more than pseudo-intellectual rationalization; “Still, he made it serve.”

Ndibe’s novel takes on serious themes of cultural exchange, but it does so in a decidedly comic fashion. All the characters Ike encounters, in New York and in Nigeria, inject their own brands of humor into the story. His ex-wife, Bernita, expresses libidinous zeal with precision and rapturous vulgarity; Ike’s friend Big Ed, a fellow cabbie, offers acerbic wisdom: “Listen, man, you ever see a one-legged man winning an arse-kicking contest?” Big Ed asks.

When Ike travels to Nigeria, fun and trouble quickly follow. Ndibe captures the elliptical poetry of the Nigerian patois, in both Igbo (rendered as English) and pidgin English. The most colorful character from Ike’s home village is Ike’s old classmate Tony Iba, who earned the moniker Tony Curtis by imitating the American actor’s mannerisms and facial expressions. “Chief Iba,” now chair of the local government council, speaks “a brew of English of his own invention, at once ungrammatical and alluring.” Iba explains to Ike that, while he is “quartered” most of the year in Nigeria, “My missus and childs say the heat is three much here. So therefore they navigated abroad to London where God blows AC inside the air. My own is to sufferate for them to enjoy.”

When Ike travels to Nigeria, fun and trouble quickly follow. Ndibe captures the elliptical poetry of the Nigerian patois, in both Igbo (rendered as English) and pidgin English. The most colorful character from Ike’s home village is Ike’s old classmate Tony Iba, who earned the moniker Tony Curtis by imitating the American actor’s mannerisms and facial expressions. “Chief Iba,” now chair of the local government council, speaks “a brew of English of his own invention, at once ungrammatical and alluring.” Iba explains to Ike that, while he is “quartered” most of the year in Nigeria, “My missus and childs say the heat is three much here. So therefore they navigated abroad to London where God blows AC inside the air. My own is to sufferate for them to enjoy.”

What’s at stake in Ike’s dilemma, Ndibe makes clear, are two competing narratives that would define the people of southeastern Nigeria: either they remain essentially African, with active beliefs in the ancient gods of their forefathers, or they are global citizens whose culture can be tossed aside and replaced by whatever Western influence happens to drift into the region. Ike prefers his uncle’s pagan virility and connection to the earth over the flimsy, “invisible” claims of Christianity and its corrupt representative in his hometown. At his best moments, Ike feels compelled to protect his uncle’s god, not steal it for his own, base purposes.

Those practical concerns never drift far from Ike’s mind, however. Beyond his own selfish motivations, Ike also knows that there are times—as when a deity “turns on the community it’s supposed to protect”—when it is the village’s best interest to kill a god. In this respect, Ike seems less like an American trying to thrive in New York than an African with the fate of his village resting in his hands.

Okey Ndibe will read from Foreign Gods, Inc. at Parnassus Books in Nashville on January 19, 2014, at 2 p.m.