The stories of the late Willie Thomas Sr. are what legends are made of. There are two versions of the first and only time Thomas entered a rodeo in Lake Charles, Louisiana, back in the early 1950s. They both end the same way.

In one version, it wasn’t until he was in the bucking chute warming up his bull rope on the back of a big-horned, brindle-colored bucking bull he randomly drew that its owner noticed the color of Thomas’s skin. He was Black. The brim of his cowboy hat had been pulled down low to shield his face, so it wasn’t until the man saw Thomas’s black hand reach up and grab the tail of his rope and pull it tight across his riding hand that the stock contractor realized his bull was matched up with the only Black bull rider in the draw that night.

As the man finished cinching up the flank strap around the bull’s back hips, he leaned over Thomas’s left shoulder and addressed him as boy. In no uncertain terms, he told Thomas if he didn’t buck off, he had better jump off that damn bull or he would “shoot his Black ass off” before the timekeeper had a chance to blow the eight-second whistle.

Thomas calmly finished tying his riding hand into his rope and, without turning to face the contractor, told him, “You better get your gun ready …” Then he reached up to push his hat down tight around his head. He didn’t want it coming off during the ride. Thomas, who lost his left eye when he was five and had it replaced with a glass replica, never saw the man when he added, “… because this one’s already rode.”

In the other version, the verbal confrontation took place beforehand.

In either case, eight seconds later, Thomas did not pound his chest, victoriously throw his hat across the arena, or even wave to the crowd — many of whom did not realize they were standing on their feet and cheering for a Black man.

When the dust settled, he unassumingly picked up his rope and hustled behind the chutes, took off his chaps and spurs, threw them in his gear bag and was rolling up his rope when he was told he needed to leave.

Based on his score, Thomas would have placed second.

He asked about his money and was told there was not going to be any for him.

Instead, after some salty language, two men told Thomas, “You’re lucky to be leaving here, and don’t you ever come back.”

They escorted him 34 miles west on Interstate 10 just to make sure he crossed the border into Texas and went back to wherever he came from. Thomas drove another 110 miles all the way to Houston, and for the rest of his life — Thomas died April 24, 2020, at age ninety — whenever he retold that story, it ended with him saying, “I never went back.”

They escorted him 34 miles west on Interstate 10 just to make sure he crossed the border into Texas and went back to wherever he came from. Thomas drove another 110 miles all the way to Houston, and for the rest of his life — Thomas died April 24, 2020, at age ninety — whenever he retold that story, it ended with him saying, “I never went back.”

Willie Thomas Sr. was born in Richmond, Texas, on January 30, 1930, and raised nearby on the A. P. George Ranch, where his parents — Johnnie and Josephine — had been living and working since 1925. His daddy had a house on the property.

The second of four children, Willie dropped out of school in the fourth grade and, by the time he was twelve, was working alongside grown men. Whenever they would finish feeding the cattle, young Willie would jump from the feed wagon onto the back of a bull, where he learned how to ride without even using a rope. At sixteen, he was put in charge of overseeing more than five hundred head of beef cattle.

The George Ranch would also provide livestock for local rodeos. Willie and his younger brother, James, would ride along, and those jackpot events were really their introduction to rodeo.

Two years later, at eighteen, Willie started competing, but without anyone to serve as a mentor or teach him the fundamentals of bull riding, he had no idea he was putting his rope on backward. He also taught himself how to ride in the bareback competition just by watching others.

His first event was in Hempstead, Texas. The entry fee was only $3. Then came Prairie View, followed by the famous Diamond L Ranch on South Main in Houston, where they held Black rodeos on Sunday afternoons. He started riding at Diamond L in 1948.

In 1953 he entered his first pro rodeo in San Antonio.

He was still riding with his bull rope on backward, but much like the incident in Lake Charles, there are a few versions as to how San Antonio played out. There are those who say he won the bull-riding event, while others claim he finished second. There’s no record of the event — only fading memories — but logic says there is no way both judges marked him high enough to win the event, much less place in the average and win money.

But one aspect of the decades-old story has been consistent for nearly seventy years. Hall of Fame cowboy Jim Shoulders was fascinated by how well Willie rode.

Shoulders had four re-ride bulls that none of the cowboys — regardless of their ethnicity — wanted to get on, so after the event Shoulders offered Willie $10 for each of the four bulls he successfully rode for eight seconds.

Willie went home with four ten-dollar bills in his pocket.

Soon after, there was an incident in Arkansas.

Without consulting the Negro Motorist Green Book — an annual guide published from 1936 to 1966 to help Black travelers with friendly motels, restaurants, and gas stations — Willie was left to spend the night in his car after a motel manager refused him service because he was Black. He drove to the rodeo arena and tried to spend the night in his car, but it was so uncomfortable that he wound up sleeping on the bleachers.

Then came a return trip back to San Antonio when Willie rode his bull well past the qualified eight seconds, but the timekeeper would not blow his whistle until after Willie stepped off his bull.

He was marked with a no score even though onlookers said Willie had ridden for almost fourteen seconds. Afterward, it has been said that rancher and stock contractor Zeno Farris confronted the timekeeper — telling him that he ought to be ashamed of himself.

Willie said nothing.

Discouraged by how he was treated, it was more than a year before he competed at another professional rodeo. When he returned — in 1956 — Willie was known for telling judges, “You might cheat me, but you won’t buck me off.”

San Antonio would not be the last time Willie was cheated.

Bobby Steiner was eleven years old and ten years from becoming the 1973 world champion bull rider when his father, Tommy, produced a rodeo in McAlester, Oklahoma.

Willie drew a red bull with big horns that had #31 on its ear tag. That bull was one of Tommy’s best and had been selected for the NFR a year earlier. “Willie Thomas spurred the shit out of him,” recalled Bobby, but one of the judges claimed Willie slapped the bull with his freehand. “My dad went, ‘What do you mean no score?’”

Bobby overheard the judge tell his dad, “He slapped him.”

Tommy confronted the judge, who told him, “Well, he’s Black, isn’t he?”

“And my dad said, ‘You’ll never work for me again,’” Bobby recalled. “It was one of the great bull rides.”

Willie didn’t cuss or say one word. He just smiled and went on.

“I’ll never forget that,” Bobby said. “After they saw how good he was, the people that were racist, they got over it.”

Bobby was not alone in his assessment of Willie. Donnie Gay, an eight-time world champion bull rider, remembers Willie as “probably the best Black bull rider, maybe ever.” Bubba Goudeau, another tough son of a bitch in his own right, agreed.

And then there’s Pete Logan, a Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame announcer who lent his voice to events at Madison Square Garden a record ten times. Before Logan died in October 1993, Bobby sat with him at a restaurant and Logan told him Willie Thomas and Harry Tompkins were two of the all-time greats.

“I never heard him give compliments,” said Bobby of his last conversation with Logan. “It’s like, damn, at that time, I thought maybe I was the only guy that felt Willie Thomas was over-the-top great, but for Pete Logan to say that was incredible. … Willie needs to know that Pete told me that.”

Harold Cash made sure he knew it.

Willie not only made a great impression on his white counterparts, but he also was an incredible influence on other Black cowboys — namely Freddie “Skeet” Gordon and Cash.

Gordon grew up with Willie on the A. P. George Ranch and later traveled with him to pro rodeos in New York City at the old Madison Square Garden and Boston, where Willie won another rodeo at the famed Boston Garden. In addition to New York and Boston, Willie won pro events in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Waco and Austin, Texas. He won twenty pro buckles in all.

In the later years of a career that lasted until 1969, Willie befriended and became something of a father figure to a kid named Cash.

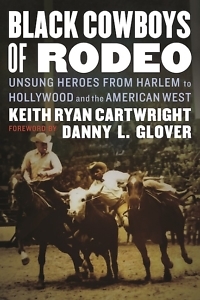

© 2021 by Keith Ryan Cartwright. Excerpted from “Willie Thomas Sr. and Harold Cash” in Black Cowboys of Rodeo: Unsung Heroes from Harlem to Hollywood and the American West, forthcoming from University of Nebraska Press in November 2021. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Keith Ryan Cartwright is a communications specialist for the Rutherford County Board of Education, adjunct professor at Middle Tennessee State University, and journalist. He is the co-author of Professional Bull Riders: The Official Guide to the Toughest Sport on Earth (Triumph Books, 2009).

Tagged: Book Excerpt